By John Scales Avery

Why the book is important

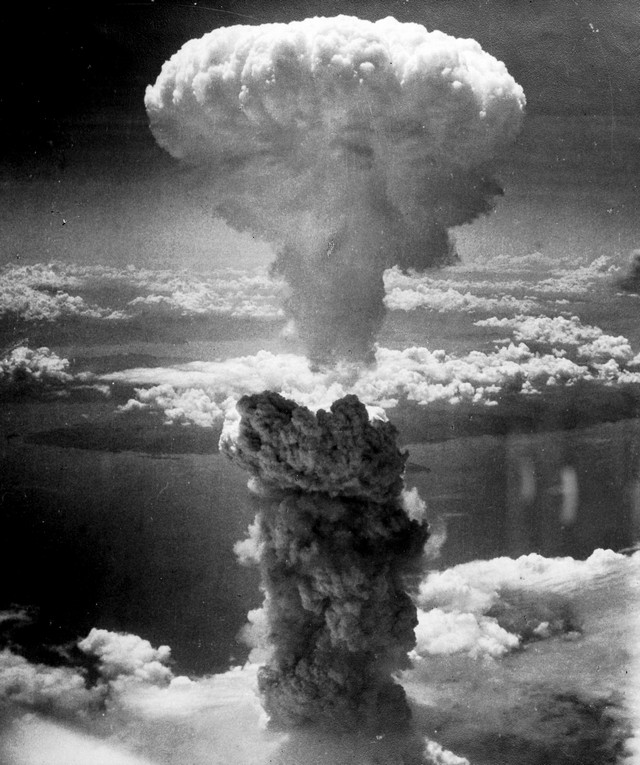

The nuclear destruction of Hiroshima was a tragedy in itself, but its larger significance is that it started a nuclear arms race which today threatens to destroy human society and much of the biosphere.

Sokka Gakki

Sokka Gakki is a large Nichirin Buddhist religious group. Its 12 million members are centered primarily in Japan, but Sokka Gokkai International (SGI) has groups in 192 countries. In Japanese, the words “Sokka Gakkai” mean “Value-Creating Education”. The organization was started by two Japanese educators, Tsunisaburo Makiguchi and Josei Toda, both of whom were imprisoned by their government during World War II because of their opposition to militarism. Makaguchi died as a result of his imprisonment, but Josei Toda went on to found a large and vigorous educational organization dedicated to culture, humanism, world peace and nuclear abolition.

The Toda Declaration and Daisaku Ikeda’s Proposals

In 1957, before a cheering audience of 50,000 young Sokka Gakkai members,Josei Toda declared nuclear weapons to be an absolute evil. He declared that their possession is criminal under all circumstances, and he called the young people present to work untiringly to rid the world of all nuclear weapons.

Toda was the mentor of Daisaku Ikeda, the first president SGI. Every year, President Ikeda issues a Peace Proposal, calling for international understanding and dialogue, as well as nuclear abolition, and outlining practical steps by which he believes these goals may be achieved. In his 2013 Peace Proposal, Ikeda, noted that 2015 will be the 70th anniversary of the destruction of Hiroshima, and he proposed that the NPT review conference should take place in Hiroshima, rather that in New York. He proposed that this should be followed by “an expanded global summit for a nuclear-weapon-free world”

The Hiroshima Peace Committee and the last remaining hibakushas

In Japanese the survivors of injuries from the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are called “hibakusha”.Over the years, the Sokka Gakkai Hiroshima Peace Committee has .published many books containing their testimonies. The most recent of these books, “A Silence Broken”, contains the testimonies of 14 men, now all in their late 70’s or in their 80’s, who are among the last few remaining hibakushas. All 14 of these men have kept silent until now because of the prejudices against hibakusha in Japan, where they and their children are thought to be unsuitable as marriage partners because of the effects of radiation. But now, for various reasons, they have chosen to break their silence. Many have chosen to speak now because of the Fukushima disaster.

The testimonies of the hibakushas give a vivid picture of the hell-like horrors of the nuclear attack on the civilian population of Hiroshima, both in the short term and in the long term. For example, Shigeru Nonoyama, who was 15 at the time of the attack, says: “People crawling out from crumbled houses started to flee. We decided to escape to a safe place on the hill. We saw people with melted ears stuck to their cheeks, chins glued to their shoulders, heads facing in awkward positions, arms stuck to bodies, five fingers joined together and grab nothing. Those were the people fleeing. Not merely a hundred or two, The whole town was in chaos.

“I saw the noodle shop’s wife leg was caught under a fallen pole, and a fire was approaching. She was screaming, ‘Help me!Help me!’ There were no soldiers, no firefighters. I later heard that her husband had cut off his wife’s leg with a hatchet to save her.”

“Each and every scene was hell itself. I couldn’t tell the difference between the men and the women. Everybody had scorched hair, burned hair, and terrible burns. I thought I saw a doll floating in a fire cistern, but it was a baby. A wife trapped under her fallen house was crying, ‘Dear, please help me, help me!’ Her husband had no choice but to leave her in tears.”

“…I hovered between life and death for three months, from August to October. When a fly landed on a festering wound, it would bleed white maggots in a few days. My mother shooed away the flies through the night with a fan through the night. She must have been desperately determined not to lose any more sons or daughters. My dangling skin dried and turned hard, like paper. My mother picked off the dried skin. She made a cream of straw ash and cooking oil, and applied it to my burnt head, face and fingertips, turning me black…”

The testimonies of the other hibakushas are equally horrifying.

The postwar nuclear arms race

On August 29, 1949, the USSR exploded its first nuclear bomb. It had a yield equivalent to 21,000 tons of TNT, and had been constructed from Pu-239 produced in a nuclear reactor. Meanwhile the United Kingdom had begun to build its own nuclear weapons.

The explosion of the Soviet nuclear bomb caused feelings of panic in the United States, and President Truman authorized an all-out effort to build superbombs using thermonuclear reactions – the reactions that heat the sun and stars. On October 31, 1952, the first US thermonuclear device was exploded at Eniwetok Atoll in the Pacific Ocean. It had a yield of 10.4 megatons, that is to say it had an explosive power equivalent to 10,400,000 tons of TNT. Thus the first thermonuclear bomb was five hundred times as powerful as the bombs that had devastated Hiroshima and Nagasaki The Soviet Union and the United Kingdom were not far behind.

In 1955 the Soviets exploded their first thermonuclear device, followed in 1957 b y the UK. In 1961 the USSR exploded a thermonuclear bomb with a yield of 58 megatons. A bomb of this size, two thousand times the size of the Hiroshima bomb, would destroy a city completely even if it missed it by 50 kilometers. France tested a fission bomb in 1966 and a thermonuclear bomb in 1968. In all about thirty nations contemplated building nuclear weapons, and many made active efforts to do so.

Because the concept of deterrence required an attacked nation to be able to retaliate massively even though many of its weapons might be destroyed by a preemptive strike, the production of nuclear warheads reached insane heights, driven by the collective paranoia of the Cold War. More than 50,000 nuclear warheads were produced worldwide, a large number of them thermonuclear. The collective explosive power of these warheads was equivalent to 20,000,000,000 tons of TNT, i.e., 4 tons for every man, woman and child on the planet, or, expressed differently, a million times the explosive power of the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima. Today, the collective explosive power of all the nuclear weapons in the world is about half that much, but still enough to destroy human society.

There are very many cases on record in which the world has come very close to a catastrophic nuclear war. One such case was the Cuban Missile Crisis. Robert McNamara, who was the US Secretary of Defense at the time of the crisis, had this to say about how close the world came to a catastrophic nuclear war: “I want to say, and this is very important: at the end we lucked out. It was luck that prevented nuclear war. We came that close to nuclear war at the end. Rational individuals: Kennedy was rational; Khrushchev was rational; Castro was rational. Rational individuals came that close to total destruction of their societies. And that danger exists today.”

A number of prominent political and military figures (many of whom have ample knowledge of the system of deterrence, having been part of it) have expressed concern about the danger of accidental nuclear war. Colin S. Gray, Chairman, National Institute for Public Policy, expressed this concern as follows: “The problem, indeed the enduring problem, is that we are resting our future upon a nuclear deterrence system concerning which we cannot tolerate even a single malfunction”. Bruce G. Blair (Brookings Institute) has remarked that “It is obvious that the rushed nature of the process, from warning to decision to action, risks causing a catastrophic mistake”… “This system is an accident waiting to happen.”

As the number of nuclear weapon states grows larger, there is an increasing chance that a revolution will occur in one of them, putting nuclear weapons into the hands of terrorist groups or organized criminals. Today, for example, Pakistan’s less-than-stable government might be overthrown, and Pakistan’s nuclear weapons might end in the hands of terrorists. The weapons might then be used to destroy one of the world’s large coastal cities, having been brought into the port by one of numerous container ships that dock every day, a number far too large to monitored exhaustively. Such an event might trigger a large-scale nuclear conflagration.

Recent research has shown that a large-scale nuclear war would be an ecological catastrophe of enormous proportions, producing very large-scale famine through its impact on global agriculture, and making large areas of the world permanently uninhabitable through long-lived radioactive contamination.

How do these dangers look in the long-term perspective? Suppose that each year there is a certain finite chance of a nuclear catastrophe, let us say 1 percent. Then in a century the chance of a disaster will be 100 percent, and in two centuries, 200 percent, in three centuries, 300 percent, and so on. Over many centuries, the chance that a disaster will take place will become so large as to be a certainty. Thus by looking at the long-term future, we can see that if nuclear weapons are not entirely eliminated, civilization will not survive.

We will do well to remember Josei Toda’s words: “Nuclear weapons to be an absolute evil. Their possession is criminal under all circumstances”

John Avery received a B.Sc. in theoretical physics from MIT and an M.Sc. from the University of Chicago.

09 August, 2014

Countercurrents.org