By Mickey Z

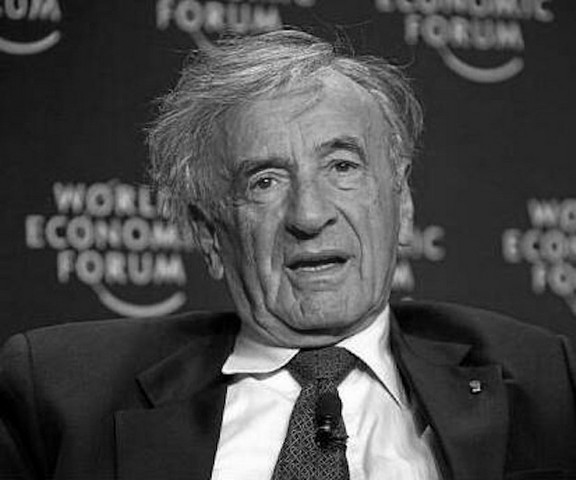

When news of Elie Wiesel’s death broke on July 2, the predictable paeans and plaudits flowed. President Barack Obama, for example, called his fellow Nobel Peace Prize winner “the conscience of the world.”

As for me, I instead reflected back to July 4, 2004, when Parade Magazine to hired Wiesel to pen a little something for Independence (sic) Day called “The America I Love” — for their patriotic cover story.

Over a two-page spread, the “Nobel Laureate” explained how America “for two centuries, has stood as a living symbol of all that is charitable and decent to victims of injustice everywhere … where those who have are taught to give back.” He explained that in the United States, “compassion for the refugee and respect for the other still have biblical connotations.”

Those same thoughts coming from a Trump voter in Peoria would be chalked up to ignorance, so perhaps Elie Wiesel was just an idiot, too simple-minded to discern reality from fantasy? But we can’t let him off the hook so easily when, after reminding us — yet again — of his Holocaust experiences, the winner of the Presidential Medal of Freedom admitted, “U.S. history has gone through severe trials” (apparently this is how Nobel Peace Prize winners think: it’s “history” that undergoes trials).

Ever careful to point out his bearing witness to the civil rights movement (and equally careful to avoid explaining what that means), Wiesel called anti-black racism “scandalous and depressing.” But, take heart, black America, because dear Elie added “racism as such has vanished from, the American scene.”

Roll over, Mumia… and tell Sandra Bland the news.

In his 2004 essay, Wiesel deigned to mention a few more of America’s indiscretions but was at the ready to explain: “No nation is composed of saints alone. None is sheltered from mistakes and misdeeds” (more scholarly talk: “mistakes,” not “policy”). “America is always ready to learn from its mishaps,” he writes. “Self-criticism remains its second nature.”

This is the territory of madmen and commissars. Who else speaks such words… and is convinced they speak the truth? Precisely what kind of man is this professional hero, Elie Wiesel? Here are two peeks behind the myth:

While Wiesel’s documentation of the Nazi Holocaust earned him international acclamation, he was not always predisposed to yield the genocide victim’s spotlight. In 1982, for example, a conference on genocide was held in Israel with Wiesel scheduled to be honorary chairman, but the situation became complicated when the Armenians wanted in.

Here’s how Noam Chomsky described the incident: “The Israeli government put pressure upon (Wiesel) to drop the Armenian genocide. They allowed the others, but not the Armenian one. He was pressured by the government to withdraw, and being a loyal commissar as he is, he withdrew… because the Israeli government had said they didn’t want Armenian genocide brought up.”

Wiesel went even further, calling up noted Israeli Holocaust historian, Yehuda Bauer, and pleading with him to also boycott the conference. “That gives an indication of the extent to which people like Elie Wiesel were carrying out their usual function of serving Israeli state interests,” Chomsky explains, “even to the extent of denying a holocaust, which he regularly does.”

Why not welcome the Armenians, you wonder? Chalk it up to two conspicuous factors: the need to monopolize the Holocaust™ image and the geopolitical reality that Turkey (the nation responsible for the Armenian genocide) has been a rare Muslim ally for Israel.

In Parade, Wiesel also spoke of brave American soldiers bringing “rays of hope” to the people of Iraq. Even if this blatant delusion bore even an iota of truth, a reminder: such hopeful rays were not welcome in Central and South America in the 1980s, when Israel served as a U.S. proxy for proving arms to murderous regimes like that of Guatemala. In 1981, shortly after Israel agreed to provide military aid to this oppressive regime, a Guatemalan officer had a feature article published in the army’s Staff College review.

In that article, the officer praised Adolf Hitler, National Socialism, and the Final Solution — quoting extensively from Mein Kampf and chalking up Hitler’s anti-Semitism to the “discovery” that communism was part of a “Jewish conspiracy.” Despite such seemingly incompatible ideology, Israel’s estimated military assistance to Guatemala in 1982 was $90 million.

What type of policies did the Guatemalan government pursue with the help they received from a nation populated with thousands of Holocaust survivors? Consider the words of Gabriel, one of the Guatemalan freedom fighters interviewed in 1994 by Jennifer Harbury: “In my country, child malnutrition is close to 85 percent. Ten percent of all children will be dead before the age of five, and this is only the number actually reported to government agencies. Close to 70 percent of our people are functionally illiterate. There is almost no industry in our country — you need land to survive. Less than 3 percent of our landowners own over 65 percent of our lands. In the last fifteen years or so, there have been over 150,000 political murders and disappearances. Don’t talk to me about Gandhi; he wouldn’t have survived a week here.”

Similar stories can be culled from countries throughout the region, but apparently have had no effect on the rulers of the Jewish state. For example, when Israel faced an international arms embargo after the 1967 war, a plan to divert Belgian and Swiss arms to the Holy Land was implemented. These weapons were supposedly destined for Bolivia to be transported by a company managed by Klaus Barbie… as in “The Butcher of Lyon.”

One figure who might have been expected to find fault with such policy was, of course, Parade cover boy Elie Wiesel. Here is an episode from mid-1985, documented by Yoav Karni in Ha’aretz, which should put to rest any exalted expectations of the revered moralist:

When Wiesel received a letter from a Nobel Prize laureate documenting Israel’s contributions to the atrocities in Guatemala, suggesting that he use his considerable influence to put a stop to Israel’s practice of arming neo-Nazis, Wiesel “sighed” and admitted to Karni that he did not reply to that particular letter.

“I usually answer at once,” he explained, “but what can I answer to him?”

One is left to only wonder how Wiesel’s silent sigh might have been received if it was in response to a letter not about the Jewish state’s complicity in the mass murder of Guatemalans but instead about the function of Auschwitz in 1943.

In that 2004 Parade essay, Elie Wiesel claimed he discovered in America “the strength to overcome cynicism and despair.”

It sounds like what he actually overcame was honesty and compassion.

5 July 2016