By Matt Taibbi

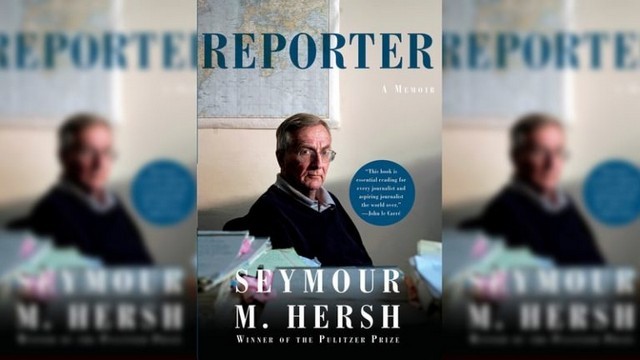

31 May 2018 – Late in his new memoir, Reporter, muckraking legend Seymour Hersh recounts an episode from a story he wrote for the New Yorker in 1999, about the Israeli spy Jonathan Pollard.

Bill Clinton was believed to be preparing a pardon for Pollard. This infuriated the rank and file of the intelligence community, who now wanted the press to know just what Pollard had stolen and why letting him free would be, in their eyes, an outrage.

“Soon after I began asking questions,” Hersh writes, “I was invited by a senior intelligence official to come have a chat at CIA headquarters. I had done interviews there before, but always at my insistence.”

He went to the CIA meeting. There, officials dumped a treasure trove of intelligence on his desk and explained that this material – much of which had to do with how we collected information about the Soviets – had been sold by Pollard to Israel.

On its face, the story was sensational. But Hersh was uncomfortable. “I was very ambivalent about being in the unfamiliar position of carrying water for the American intelligence community,” he wrote. “I, who had worked so hard in my career to learn the secrets, had been handed the secrets.”

This offhand line explains a lot about what has made Hersh completely embody what it means to be a reporter. The great test is being able to get information powerful people don’t want you to have. A journalist who is handed something, even a very sensational something, should feel nervous, sick, ambivalent. Hersh never stopped feeling that way, remaining an iconoclast and a thorn in the side of officialdom to this day.

Hersh became famous in the late-’60s and early-’70s, at a time when the country was experiencing violent domestic upheaval and investigative reporters were for the first time celebrated like rock stars.

Hersh was best known back then for his reporting on American atrocities in Vietnam, in particular the massacre of hundreds of unarmed Vietnamese in the village of My Lai. The story did a great deal to puncture the myth of American beneficence in Southeast Asia.

A significant theme of Hersh’s work is that Americans are human beings, not immune from the horrific temptations of power that throughout history have afflicted and shamed those who have dominion over others.

For this, he has often been denounced as a traitor. In advance of a speech at Tulane in the wake of My Lai, for instance, the Times-Picayune called him a “communist sympathizer” and ran an editorial literally bordered in red protesting his appearance (de-platforming was a thing even then).

Being “more than a little pissed off at the cheap shot” (an unerring sense of pissed-off-edness is another of Hersh’s gifts), he gave the speech at Tulane and decided to improvise “with a purpose in mind.”

The room was full of Vietnam vets. Hersh asked if anyone in the audience had been a helicopter pilot in a certain Vietnamese province in 1968 or 1969. A man came onstage. Once Hersh reassured him that he had no interest in his name, he asked the soldier what chopper pilots sometimes did to “cope with the rage.”

The soldier, while claiming he didn’t do it personally, said he knew what Hersh was talking about. The practice involved spotting a civilian farmer on the way back after a mission, flying low and attempting to decapitate the fleeing figure with rotor blades. The crews would have to land short of the base to “wash the blood off the rotors.”

“I did not like what I did to the vet, who was stunningly honest,” he writes, “but I wanted to get back, in some way, at the Times-Picayune.”

Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of the Washington Post will be remembered by history as the “whiz kids” who cracked Watergate, but Hersh also wrote 40 front-page articles on the affair for the Times in the space of months. Many of those pieces “[moved] the needle closer to the president,” as he puts it here.

Hersh and Woodward in particular will likely forever be linked in a Magic-Bird sort of way. The two reporters continued after the Vietnam and Watergate years to crank out heavy tomes full of secrets about everyone from Henry Kissinger (in Hersh’s case) to CIA chief Bill Casey (in Woodward’s), solidifying reputations as the country’s top investigative reporters.

But Hersh and Woodward represented two starkly different approaches to the job. Woodward is the quintessential access journalist, able to write books like Bush at War that seem to place the reader practically inside the Oval Office during crucial moments in history.

But Woodward’s information often came from the very celebrity politicians who were chief characters in these books. Piecing together these insider versions of history, probably recounted over expensive lunches off the Mall, was a more institutionalized version of “being handed the secrets.”

Hersh, on the other hand, has had success mining the middle and lower ranks of agencies. He constantly keeps an eye out for sources among the lesser-known (but still powerful) officials who are leaving the game. Many of these techniques are detailed in Reporter.

“One of my quirks,” he writes, “has been to keep track of the retirement of senior generals and admirals; those who did not get to the top invariably had a story to tell in explaining why.”

He even watches for obituaries, which often let slip surprising information about the pasts of, say, deceased CIA operatives. And he will call wives or relatives and search for information that way.

Hersh, in other words, works from the edges inward, developing a grapevine of faceless sources that in turn generate rumors and stories of things he isn’t supposed to know – a secret program to recover a sunken Russian submarine, an incident of soldiers using fire ants to torture a terror suspect – anything.

These techniques were very much on display during the post-9/11 years. Hersh put out a spate of some of the most impactful reporting on the War on Terror, lifting a lid on some of America’s most barbaric practices. The Abu Ghraib stories were the best known, and the inside tale of how those came to light is told here.

Hersh learned a great deal from a three-day visit in Damascus with an Iraqi general who’d “retired” after the Iraq army was banned. The general was making a living selling vegetables from his garden when he decided to reach out to old U.N. contacts about troubling things he’d seen and heard about. This ex-general ended up in touch with Hersh and told many “sad tales, mostly secondhand, of the horrors of the American occupation.”

He described American soldiers raiding houses and robbing the inhabitants (many Iraqis kept their savings in dollars). He described tales of arrestees who were set free for a kickback. And he told of a regime of abuse in American detention centers so horrific that men would “write to their fathers and brothers and beg them to come kill them in jail.”

Much of this couldn’t be confirmed easily, but the tales squared with reports from human rights groups. Besides, Hersh writes, “his account also smelled right” (having a sense of who is and is not lying is a key skill, often the difference between giving up and continuing to dig). Hersh kept at it and uncovered a key internal report about the abuse, and his New Yorker story was an international sensation that changed the course of another war.

An interesting side-note is that Hersh was instrumental in getting the story out before his own story ran. He knew that 60 Minutes had photos of the Abu Ghraib abuse and was “skittish” about publishing them “after being urged by the Bush administration not to do so.” Hersh, in his inimitable pain-in-the-ass way, called a CBS producer on the story and essentially told her that if CBS didn’t run the story soon, “I would have no choice but to write about the network’s continuing censorship in the New Yorker.”

The photos aired in the next 60 Minutes broadcast, and Dan Rather – who, Hersh knew, had been fighting to get the story out – made a point to say on air that CBS only published when they learned other media had the story.

“It wasn’t hard to guess that he had been ordered to make such an asinine excuse for an important news story,” Hersh writes.

Hersh was also among the first to describe a burgeoning American assassination program that to this day is poorly understood.

Within weeks of 9/11, for instance, Hersh quoted a “C.I.A. man” claiming the U.S. needed to “defy the American rule of law… We need to do this – knock them down one by one.” He later reported on the existence of a “target list” and cited an order comparing the new tactics to El Salvadoran execution squads, reporting that much of this was going on without Congress being told.

Despite his reputation for irascibility and for troubled relationships with editors, it shines through in the book that he always felt tremendous loyalty to people like Abe Rosenthal of the Times and David Remnick of the New Yorker, and to the great organizations they represented.

But, as Hersh puts it in the end, “Investigative reporters wear out their welcome… Editors get tired of difficult stories and difficult reporters.”

At the end of Reporter, he recounts his falling out with the New Yorker. Hersh says he became concerned when he heard Remnick was planning on writing a biography of new president Barack Obama.

Earlier in his career, Hersh himself had actually worked for the campaign of antiwar Democrat Eugene McCarthy. And he himself liked candidate Obama. But this was a church-and-state issue. He had a thing about wearing two hats at once.

Regarding Remnick’s relationship to Obama, he writes:

“I had learned over the years never to trust the declared aspirations of any politician, and was also enough of a prude to believe that editors should not make friends with a sitting president.”

Ultimately, Hersh and the New Yorker fell out over the story of the assassination of Osama bin Laden. The magazine – with the input of then-Obama counter-terrorism adviser John Brennan – ended up running the “inside” account of the operation much as the Obama administration has always told it.

Hersh, meanwhile, had sources indicating a very different version of bin Laden’s end, one in which the U.S. killed bin Laden with the assent of the Pakistani intelligence agency ISI, which had had him in captivity for years.

In the end, Hersh was forced to publish his account in the London Review of Books, which is where he’s been publishing on and off ever since.

The journalism business is undergoing radical changes. Media figures are more famous than ever before, but those with the biggest profiles tend to be associated with one particular political demographic.

The job in many quarters has devolved into feeding captive audiences a steady stream of revelations framed to fit their preconceived ideas about the world, in order to keep them coming back. From Fox to MSNBC, the slant of programming has become more predictable, because audiences hate surprises and dislike being challenged.

As Hersh puts it, in such an environment, one of the first casualties is investigative reporting, “with its high cost, unpredictable result, and its capacity for angering readers…”

Hersh’s career is a tribute to the pursuit of the “unpredictable result.” We used to value reporters who were willing to alienate editors and readers alike, if that’s the way the truth cut. Now, as often as not, we just change the channel. This has been bad for both reporters and readers, who are losing the will to seek out and face the unpredictable truth.

When it comes time for the next generation of journalists to re-discover what this job is supposed to be about, they can at least read Reporter. It’s all in here.

Matt Taibbi is a contributing editor for Rolling Stone.

4 June 2018

Source: https://www.transcend.org/tms/2018/06/seymour-hershs-memoir-is-full-of-useful-reporting-secrets/