By Nile Bowie

When regional leaders gathered in Singapore and Papua New Guinea for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (Apec) summits, many expected the United States to elaborate upon its new “Indo-Pacific” development strategy for the region.

But what began as an opportunity for the US and China to advance their competing visions for the region’s future development and economic integration ended in acrimony, with officials of the 21-member Apec grouping unable to agree for the first time on a joint communiqué as Washington and Beijing clashed over the statement’s language.

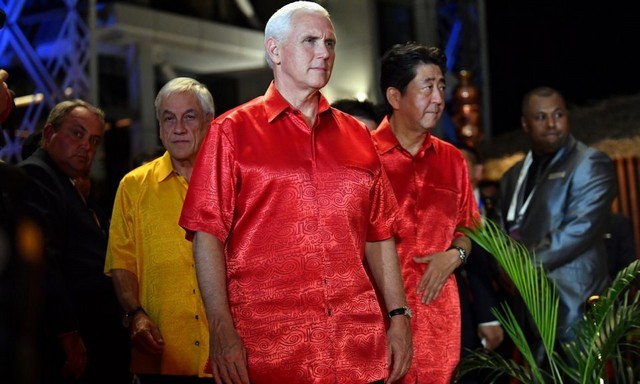

While fissures over trade, investment and maritime security between the world’s two largest economies appear no closer to resolution after the summits, speeches by US Vice President Mike Pence provided more clarity into the US’ Indo-Pacific gambit, which was unveiled in August but has so far failed to gain traction with regional leaders.

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo initially announced the strategy to include a US$113 million investment package for technology, energy and infrastructure that he called a “down-payment on a new era of US economic commitment to the region.” That new commitment was unveiled alongside US$300 million in new funding for security cooperation.

Doubts about the strategy, seen by many as a vague move to counterbalance China’s economic heft, were rife among observers who compared the paltry amount pledged by Washington to Beijing’s US$1 trillion Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) infrastructure-spending drive.

While US officials have been at pains to impress the plan is not competing directly with Beijing’s initiatives, Pence’s remarks at regional summits and the US’ recent mobilization of large-scale public-private investments suggest the opposite: a coordinated American response to China’s signature economic initiative, backed by allies such as Australia, Japan and others.

“We do not offer a constricting belt or a one-way road,” Pence told Apec summit attendees during a blunt speech in Port Moresby that, while not directly naming China, warned of opaque infrastructure financing practices that could burden nations with unsustainable debt loads.

The idea that Beijing is mobilizing development financing in a bid to ensnare strategically important regional countries into sovereignty-eroding “debt traps” has gained currency among those with hawkish views on China, though it has arguably done little to blunt the region’s general receptiveness to the initiative.

Chinese President Xi Jinping defended the BRI during his Apec summit address, denying any “hidden political agendas” to weigh down countries with debt. Pence, meanwhile, used his sharply-worded address to persuade countries to choose “the better option” of American development financing.

Washington’s emphasis on infrastructure financing – which was not a component of the Barack Obama administration’s free trade-oriented Asia ‘pivot’ strategy – follows last month’s passage of the Better Utilization of Investment Leading to Development (Build) Act, which received rare bipartisan support from the US Congress.

The Build Act mandates the creation of a new agency, the US International Development Finance Corp (IDFC), which will make development financing loans and guarantees available around the world, giving – according to the White House – developing countries a viable alternative to “state-directed initiatives that come with hidden strings attached.”

The new legislation provides the soon-to-be-formed IDFC an exposure cap of US$60 billion, double what its predecessor agency, the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC), utilized for foreign aid expenditure. Unlike OPIC, the IDFC will be permitted to undertake investments in equity – just as BRI-linked lenders have done – in the global projects it finances.

That would mark a sea change from how America’s hitherto modest foreign assistance programs have operated in recent decades, generally focusing on technical assistance programs, civil society funding, disaster relief and small-scale infrastructure, rather than the big-ticket infrastructure and global development financing associated with China’s BRI.

In an op-ed published in the Washington Post, Pence wrote that the US would help build “world-class ports and airports, roads and railways, and pipelines and data lines.” Businesses, not bureaucrats, he wrote, would spearhead American efforts, “because governments and state-owned enterprises are incapable of building lasting prosperity.”

The narrative of business-led capitalism versus state-directed enterprises features prominently in the Indo-Pacific strategy’s offerings, which from the start emphasized how American private sector investment would yield more “transparent” and “sustainable” outcomes for developing countries.

Allied nations are also tipped to play a significant role, with Australia and Japan recently unveiling plans to collaborate with Washington on the funding of regional infrastructure programs.

All three countries, along with India, are part of the so-called Quadrilateral (Quad) security alliance that Beijing views as part of an ill-intentioned containment strategy.

Although the IDFC’s US$60 exposure cap pales in comparison to China’s development financing expenditure, some observers argue Washington could have an edge as a lender by offering mixed financing options that tap into strategic banking and private sector partners, as well as foreign lenders such as Japan, that offer concessionary interest rates.

IDFC won’t be formally established until 2019, and in the meantime, there is an ongoing discussion within the Trump administration regarding the implementation of new funding for American private sector companies, according to Michael Michalak, senior vice president and regional managing director of the US-ASEAN Business Council.

Michalak, a former US ambassador to Vietnam, told Asia Times that while the private sector will “try and get as much capital as they can” for use in projects across the region, members of the business community are “much more obviously pro-trade than the current administration” and not in favor of the White House’s policies toward China.

“I would say, everybody, without exception, thinks a trade war is a bad idea and that eventually it is going to hurt everybody involved,” he said. “The focus should be on rebuilding relationships with our trading partners, to try and use those relationships to get at the China issue, rather than going at it alone with heavy-handed tariff tactics.”

Michalak says the Trump administration’s trade policies and retreat from multilateralism have brought about “uncertainty” that has undermined American influence in the region. “Every time I talk with administration representatives at embassies or elsewhere, they are not talking about multilateral initiatives. It’s all bilateral.

“By doing bilateral, you’re not going to affect the entire rules-based system in a way that doing a multilateral agreement would,” says Michalak. “I don’t see them doing any multilateral initiatives, and, going forward, I don’t see the US as having the same kind of influence that it had in past administrations.”

Despite the Trump administration casting its global development financing aspirations as an alternative to China’s infrastructure spending, Michalak believes the American initiative is not intended to “go head-to-head” with BRI. The Build Act “is simply trying to improve the competitiveness of American companies in the infrastructure space,” he says.

By pulling back from multilateral trade deals, however, “the US just risks being left behind as the rest of the world is moving forward with integration and trying to decide rules on the digital economy,” said Michalak.

Despite bipartisan consensus among US lawmakers for countering Chinese initiatives, countries in the region appear more preoccupied with maneuvering around Washington’s zero-sum approach to trade and worsening ties with Beijing. And with multilateralism in tatters, witnessed in the Apec debacle, it remains to be seen whether Trump’s Indo-Pacific vision will have many takers.

Nile Bowie is a writer and journalist with Asia Times covering current affairs in Singapore and Malaysia.

19 November 2018

Source: http://www.atimes.com/article/americas-indo-pacific-lacks-currency-and-resonance/