By Tengku Ahmad Hazri

MODERN citizenship is in crisis. The resurgence of identity politics is just one manifestation of this.

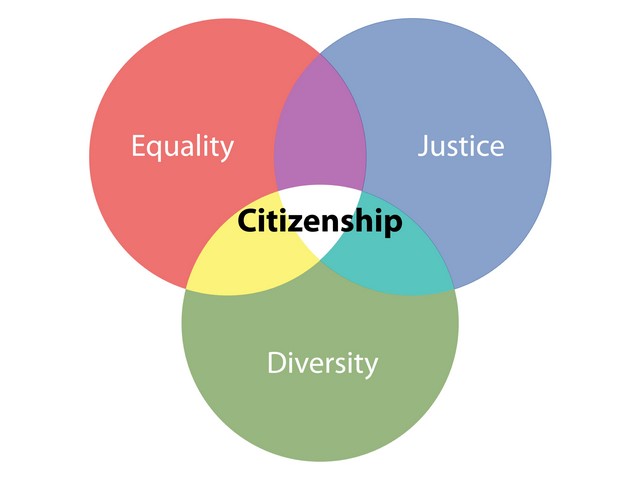

Identity politics is in fact a sign of the problem with citizenship even though it has rarely been presented or seen as such. This is because the very idea of citizenship itself serves to create a common identity, introduce equality and abolish distinctions of race, ethnicity, class and rank, among others. But in constructing a common civic identity for all citizens, states soon realise that they cannot entirely dispense with culturally specific claims.

Citizenship today has often been seen as a means to provide basic rights and protection for individuals, especially refugees and other stateless persons. This notion came about due to our innate humanitarian sensibilities and the spread of human rights, and thus, citizenship is conceived as the “right to have rights”.

In recent years, due to war, civil strife, and natural calamities, the idea of citizenship as a means to provide basic rights has become dominant. The right to nationality is even enshrined as a basic human right under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).

But this notion obscures a crucial aspect of citizenship in that it has always been political. By altering citizenship laws, states could radically change the demographics of a region or territory, with far-reaching political implications. Among others this could be used to neutralise the prospects of secession, where the dominant community in that region is different from the mainstream national community, or to alter the demographic balance between different ethnic or religious groups, towards privileging or excluding one group over another. That citizenship is highly charged politically can be seen in the recent controversy sparked by India’s Citizenship (Amendment) Bill 2016 which sought to grant citizenship to undocumented non-Muslim immigrants from neighbouring Muslim-majority states of Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan. The illusion of a purely civic community can further be clearly seen in how some states still retain ethnic components as part of their citizenship requirement, such as in China, Myanmar and Israel.

The intrinsically political nature of citizenship renders this legal concept to be intertwined with culture, at times with worrying consequences as states are prepared to countenance radical measures to safeguard their identity. In such times minor gestures partake of political symbols. In 2018, France’s highest administrative tribunal, the Conseil d’Etat, upheld the denial of an Afghan woman’s citizenship when she refused a handshake with a male official during the naturalisation ceremony, seeing in the gesture a failure to integrate with French society. Later that year, Denmark passed a law making handshake a requirement during citizenship ceremony, making it a point that doing so with a hand-glove would be unacceptable.

Citizenship is thus closely linked to national identity. Although attempts have often been made to distinguish citizenship from nationality, in practice they are so closely intertwined that they are often taken to be synonymous. The UDHR proclaims the “right to nationality” (Article 15) but subsumes citizenship within this category. Whereas citizenship relates to legal status and rights, nationality often carries a broader sense of identity and belonging that often includes narratives drawn from history. Indeed, even in the West, the idea that liberal freedoms constitute the core of their identity rest partly on history, specifically the fact that historically liberty was a hard won right often paid with lives and blood.

When the European Court of Human Rights in October 2018 ruled that defaming Prophet Muhammad did not count as “free speech” critics were quick to resort to identity politics: “The European Court of Human Rights submits to Islam”, reads a think tank’s website.

Amidst debate on multiculturalism in Europe in the 1990s, the German Muslim sociologist Bassam Tibi advanced the concept of Leitkultur (lead culture) based on common European values of human rights, tolerance and the separation of church and state. Leitkultur stands for the idea that a nation needs a main or guiding culture to which its citizens — but especially immigrants seeking citizenship — should subscribe.

Yet in 2000, when Germany relaxed its citizenship laws to integrate immigrants, a politician of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), Friedrich Merz reclaimed the concept of Leitkultur as a response to multiculturalism, but rather than Tibi’s European Leitkultur, advocated for a specifically German Leitkultur instead.

The late Iranian scholar Hamid Enayat even criticised the notion of citizenship in its Latin roots. Enayat argued that the Latin word for man, “homo” indicates a bare human being without any rights, thus necessitating the creation of an artificial institution — citizenship —by which his rights are recognised. Abu’l A’la Maududi envisaged a world in which Muslims could travel freely across Muslim lands (the dar al-Islam, or “abode of Islam” in classical Islamic law) carrying only their faith as their “citizenship”. Sayyid Qutb similarly chastised the modern state system and dreamt of a world where “nationalism is belief, homeland is dar al-Islam, the ruler is God, and the constitution is the Quran”.

The Turkish scholar-statesman, Ahmet Davutoglu sees the concept of ummah as an “open society for any human being who accepts (divine) responsibility regardless of his origin, race or colour”.

Thus, although contemporary depictions of identity politics often frame religious identity as a challenge to “civic identity” based on common citizenship, within Islamic discourse itself, it is this religious unity grounded in faith and the spiritual fraternity of mankind that transcends the artificial dichotomies offered by territoriality and birth.

The challenge, therefore, is not between “civic” and “religious” identities, but competing notions of “civic” identities.

The rise of identity politics has exposed the limits to the ideals of civic citizenship as it questions the boundaries between civic and other forms of identities.

The writer is research fellow at International Institute of Advanced Islamic Studies Malaysia, with interests in law (especially constitutional law and theory), jurisprudence and contemporary Islamic thought and civilisation. He is also Secretary-General of JUST.

16 May 2019