By Prof Hoosen Vawda

The Targeted, Severe Torture and Brutal Murder of Political Activists by the Agents of the South African Apartheid Regime [i]

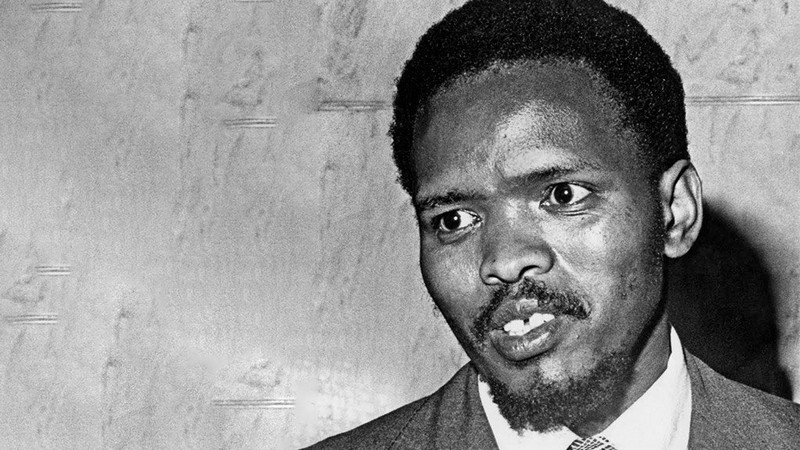

23 Jul 2022 – In Part 2 of this series, the author discussed the untimely, unsolved death of Dr Neil Hudson Aggett on 06th October 1983, while in security police detention in Johannesburg, South Africa.[1] This paper examines the life of another apartheid martyr, Bantu Stephen Biko, born on 18th December 1946 into a Xhosa family in King William’s Town, Eastern Cape, South Africa and brutally killed while in South African security police detention on 12th September 1977. In the wake of the urban revolt of 1976 and with prospects of a national revolution becoming apparent, security police detained Biko, the outspoken student leader, on 18th August 1977. He was thirty years old and was reportedly extremely fit when arrested. He was detained in Port Elizabeth and on 11th September moved to Pretoria Central Prison, Transvaal (now Gauteng)[2]. His untimely demise began in a Pretoria prison cell for his anti-apartheid stance against the white minority government of that era in South Africa. He died in detention, the 20th person to have died in detention in the preceding eighteen months.[3] A post-mortem was conducted the day after Biko’s death, at which his family was present. The explanation given by the Minister of Justice and Police, Jimmy Kruger[4], was that Biko died while on a hunger strike.[5] A number of South African newspapers did their own private investigations and learned that Biko died from brain injuries. Their investigations also revealed that Biko was assaulted before he was transported to Pretoria without any medical attention. Three South African newspapers carried reports that Biko did not die as a result of a hunger strike.[6]

The night of 12th September 1977, in South Africa, was a warm balmy, late autumn evening, which began for Steve Biko in a small prion cell in the morning, in Pretoria, the capital of South Africa when he was brutally assaulted on the left side of his head, by the apartheid interrogators resulting in a brain haemorrhage. He was then placed in the back of a non-white police van , without any medical support, let alone a mattress, while frothing at his mouth and made to endure a 700-mile-long journey, in a mortally injured condition to eventually die on arrival at a state prison hospital for Blacks, that night. The night is also a religiously significant night for Muslims, called the “Night of Power” in the Islamic, lunar calendar which is approximately ten days shorter than the Gregorian system of counting the days. Steve Biko died on a night that Muslims consider better than a thousand months. Some today, like yesterday, may begin to wonder, “ do Black Lives Matter to God?” The Night of Power is a pivotal, holy night, according to Muslims, in which angels repeatedly descend from heaven seeking to bestow blessings of Divine intervention for those standing on earth imploring God’s help. God describes this night as qualitatively better than a thousand months, which is greater than a lifetime. This night can be described as pivotal for two reasons: The first is that this intervention changes the course of history as when God first sent the Angel Gabriel with the Holy Qur’an on his last mission to mankind. The second is that in this way the hosts of angels coming to earth are on a spiritual intervention for believers, creating in them an internal peace in an oppressive period of time. In the chapter called The Night of Power, both these pivotal purposes are explained: “We sent it down on the Night of Power. What will explain to you what that Night of Power is? The Night of Power is better than a thousand months; on that night the angels and the Spirit descend again and again with their Lord’s permission on every task. Peace it is until the rising of the dawn.” (Qur’an 97: 1–5)

One of those difficult moments of pivotal convergence was the night Steve Biko was violently martyred. In the Islamic calendar, Steve Biko’s death was caused on the 27th night of Ramadan in the year of 1397, after the migration of the Messenger of God, the Prophet Muhammad , from Mecca where he was persecuted by the people of his own tribe for spreading a relatively new religion of Islam, to Medina, where his doctrine was well received. This is the beginning of the Islamic calendar. The Night of Power, which incidentally fell on September 12, 1977, when Steve Biko died. The question which is often raised by Islamic Scholars is “How can such a disruption of peace and injustice take place on the Night of Power when the angels are descending granting peace until the rising of the dawn?“ Biko’s brutal murder created a theodicy question that would lead some to form a negative opinion about God and the value of Black lives to God. Muslim theology teaches that God has the prerogative to take what belongs to Him, and one of those angels that descended was the angel of death who was commanded to take the soul of Steve Biko. Despite the evil of a thousand blows that night that White supremacy thought it was killing a Black man in attempt to silence the voice that yelled the loudest that Black Lives Matter, to believers in God’s eternal power, this night was still better than a thousand months. It was a pivotal moment in the anti-apartheid movement which ended the life of the struggle in South Africa. Steve Biko was beaten to death while in Police custody, a familiar dark and brutal reality yesterday and even in the 21st century, if the person is of African origins, today, globally.[7]

Until this late autumn night in 1977, Biko was an outspoken leader of the South African Liberation Movement against apartheid in the decades after the former, first democratically elected President Nelson Mandela’s imprisonment, in Robben Island off the shoreline of the beautifully scemic coast of the Southern tip of South Sfrica. For almost 27, long years. Steve Biko spoke about the ambiguous nature of life and death and what a good life meant to him: “You are either alive and proud or you are dead, and when you are dead, you can’t care anyway.” Although Steve Biko is physically gone, he is alive and victorious because he lived caring for his fellow South Africans, repelling evil with good. The Muslims believe by the power of God that all martyrs live beyond their mortal life and are commanded not to refer to those slain while fighting for peace and justice as dead.[8] The Quran, Holy Book of Islamic faith categorically states that: “Do not say that those who are killed in God’s cause are dead; they are alive, though you do not realize it.” Qur’an 2:154.[9]

Bantu Stephen Biko was a South African anti-apartheid activist. Ideologically an African nationalist and African socialist, he was at the forefront of a grassroots anti-apartheid campaign known as the Black Consciousness Movement during the late 1960s and 1970s. His ideas were articulated in a series of articles published under the pseudonym Frank Talk.

Raised in a poor Xhosa family, Biko grew up in Ginsberg township in the Eastern Cape. In 1966, he began studying medicine at the University of Natal, where he joined the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS). Strongly opposed to the apartheid system of racial segregation and white-minority rule in South Africa, Biko was frustrated that NUSAS and other anti-apartheid groups were dominated by white liberals, rather than by the blacks who were most affected by apartheid. He believed that well-intentioned white liberals failed to comprehend the black experience and often acted in a paternalistic manner. He developed the view that to avoid white domination, black people had to organise independently, and to this end he became a leading figure in the creation of the South African Students’ Organisation [10](SASO) in 1968. Membership was open only to “blacks”, a term that Biko used in reference not just to Bantu-speaking Africans but a[11]lso to Coloureds and Indians. He was careful to keep his movement independent of white liberals, but opposed anti-white hatred and had white friends. The white-minority National Party government were initially supportive, seeing SASO’s creation as a victory for apartheid’s ethos of racial separatism.

Influenced by the Martinican philosopher Frantz Fanon and the African-American Black Power movement, Biko and his compatriots developed Black Consciousness as SASO’s official ideology. The movement campaigned for an end to apartheid and the transition of South Africa toward universal suffrage and a socialist economy. It organised Black Community Programmes (BCPs) and focused on the psychological empowerment of black people. Biko believed that black people needed to rid themselves of any sense of racial inferiority, an idea he expressed by popularizing the slogan “black is beautiful”. In 1972, he was involved in founding the Black People’s Convention (BPC) to promote Black Consciousness ideas among the wider population. The government came to see Biko as a subversive threat and placed him under a banning order in 1973, severely restricting his activities. He remained politically active, helping organise BCPs such as a healthcare centre and a crèche in the Ginsberg area. During his ban he received repeated anonymous threats, and was detained by state security services on several occasions. Following his arrest in August 1977, Biko was beaten to death by state security officers. Over 20,000 people attended his funeral.

During his life, Biko had many unhappy experiences which defined his future strategy in the fight for racial equality. One incident is notewortyhy of mention. NUSAS officially opposed apartheid, but it moderated its opposition in order to maintain the support of conservative white students.[12] Biko and several other black African NUSAS members were frustrated when it organised parties in white dormitories, which black Africans were forbidden to enter.[13] In July 1967, a NUSAS conference was held at Rhodes University in Grahamstown. After the student delegations arrived, they found that dormitory accommodation had been arranged for the white and Indian delegates, but not the black Africans, who were told that they could sleep in a local church. Biko and other black African delegates walked out of the conference in anger.[14] Biko later related that this event forced him to rethink his belief in the multi-racial approach to political activism.[15] Biko expressed the following sentiments. “I realised that for a long time I had been holding onto this whole dogma of nonracism, almost like a religion, But in the course of that debate I began to feel there was a lot lacking in the proponents of the nonracist idea, they had this problem, you know, of superiority, and they tended to take us for granted and wanted us to accept things that were second-class. They could not see why we could not consider staying in that church, and I began to feel that our understanding of our own situation in this country was not coincidental with that of these liberal whites.[16]

“Black”, said Biko, “is not a colour; Black is an experience. If you are oppressed, you are Black. In the South African context, this was truly revolutionary. Biko’s subsidiary message was that the unity of the oppressed could not be achieved through clandestine armed struggle; it had to be achieved in the open, through a peaceful but militant struggle.”[17]

Biko hoped that a future socialist South Africa could become a completely non-racial society, with people of all ethnic backgrounds living peacefully together in a “joint culture” that combined the best of all communities.[18] He did not support guarantees of minority rights, believing that doing so would continue to recognise divisions along racial lines.[19] Instead he supported a one person, one vote system.[20] Initially arguing that one-party states were appropriate for Africa, he developed a more positive view of multi-party systems after conversations with Woods.[21] He saw individual liberty as desirable, but regarded it as a lesser priority than access to food, employment, and social security.[22] Dr Saths Cooper, a former Vice-Chacellor of the University of Durban-Westville, a tertiary, apartheid institute, specfically built for Indian students, was also a good friend of Steve Biko, as a ploitcal activist.[23]

Biko’s fame spread posthumously. He became the subject of numerous songs and works of art, while a 1978 biography by his friend Donald Woods formed the basis for the 1987 film Cry Freedom. During Biko’s life, the government alleged that he hated whites, various anti-apartheid activists accused him of sexism, and African racial nationalists criticised his united front with Coloureds and Indians. Nonetheless, Biko became one of the earliest icons of the movement against apartheid, and is regarded as a political martyr and the “Father of Black Consciousness”. His political legacy remains a matter of contention, amongst the academic and plitical fraternities not only in South Africa, but globally.

Following apartheid’s collapse, in 1994, Donald Woods[24] a South African journalist and anti-apartheid activist, raised funds to commission a bronze statue of Biko from Naomi Jacobson[25]. It was erected outside the front door of city hall in East London on the Eastern cape, opposite a statue commemorating British soldiers killed in the Second Boer War.[26] Over 10,000 people attended the monument’s unveiling in September 1997.[27] In the following months it was vandalised several times; in one instance it was daubed with the letters “AWB”, an acronym of the Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging, a far-right Afrikaner paramilitary group.[28] In 1997, the cemetery where Biko was buried was renamed the Steve Biko Garden of Remembrance.[29] The District Six Museum also held an exhibition of artwork marking the 20th anniversary of his death by examining his legacy.[30]

Also in September 1997, Biko’s family established the Steve Biko Foundation.[31] The Ford Foundation donated money to the group to establish a Steve Biko Centre in Ginsberg,[32] opened in 2012.[33] The Foundation launched its annual Steve Biko Memorial Lecture in 2000, each given by a prominent black intellectual.[34] The first speaker was Njabulo Ndebele; later speakers included Zakes Mda, Chinua Achebe, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, and Mandela.[35]

Buildings, institutes and public spaces around the world have been named after Biko, such as the Steve Bikoplein in Amsterdam.[36] In 2008, the Pretoria Academic Hospital was renamed the Steve Biko Hospital.[37] The University of the Witwatersrand has a Steve Biko Centre for Bioethics.[38] In Salvador, Bahia, a Steve Biko Institute was established to promote educational attainment among poor Afro-Brazilians.[39] In 2012, the Google Cultural Institute published an online archive containing documents and photographs owned by the Steve Biko Foundation.[40] On 18 December 2016, Google marked what would have been Biko’s 70th birthday with a Google Doodle.[41] The University of KawaZulu-Natal, Nelson R. Mamdela School of Medicine, in Durban, eponymously named only a lecture theatre as the “Steve Biko Lecture Theatre, noting that Steve Biko was a medical student there, pior to his arrest and death.[42]

Amid the dismantling of apartheid in the early 1990s, various political parties competed over Biko’s legacy, with several saying they were the party that Biko would support if he were still alive.[43] AZAPO[44] in particular claimed exclusive ownership over Black Consciousness.[45] In 1994, the ANC issued a campaign poster suggesting that Biko had been a member of their party, which was untrue.[46] Following the end of apartheid when the ANC formed the government, they were accused of appropriating his legacy. In 2002, AZAPO issued a statement declaring that “Biko was not a neutral, apolitical and mythical icon” and that the ANC was “scandalously” using Biko’s image to legitimise their “weak” government. Members of the ANC have also criticised AZAPO’s attitude to Biko; in 1997, Mandela said that “Biko belongs to us all, not just AZAPO.” On the anniversary of Biko’s death in 2015, delegations from both the ANC and the Economic Freedom Fighters independently visited his grave.[280] In March 2017, the South African President Jacob Zuma laid a wreath at Biko’s grave to mark Human Rights Day.[47]

Bantu Stephen Biko, one of South Africa’s most famous anti-apartheid sons, was martyred at the hands of White, South Africa security police. Soon after, an autopsy was conducted and photographs were taken. Images from this report were leaked to the South African press and appeared in newspapers on 20th September 1977. When journalists received the official autopsy report on 26th October 1977, South Africans as well as the rest of the humane global community, had evidence-based confirmation of their speculations: Mr. Biko died of a massive brain hemorrhage due to blunt trauma on the left side of his head. Images from Biko’s autopsy were periodically printed in South African news media, through the last quarter of 1977 as the state conducted an inquiry into his death. Over the next eight years, these pictures sometimes accompanied reports on efforts to censure state pathologists for their handling of Biko’s medical needs prior to his death. Thus, through popular reproduction over a lengthy period, Biko’s postmortem portraits reached a large and unquantifiable audience, nationally in South Africa, as well as the global media, creating an awareness of the appalling human rights abuses in South Africa by the White, governing minority, against the Black majority.[49]

Like portraits made while he lived, images of Biko’s corpse have become potent symbols for wider cultural notions about changing power relations, order and disorder, and conceptions of self within the society. Julia Kristeva defines the corpse as the utmost of abjection.[50] She famously wrote that it is “not lack of cleanliness or health that causes abjection but what disturbs identity, system, and order. What does not respect boundaries, positions, or roles. The in-between, the ambiguous, the composite”. Since autopsies are performed when the cause of death is questioned, abjection, in all of its uncertainty, is inherent to the practice and its representation. When the pathologist’s record images of an important political activist who died at the hands of the State, viewers are compelled to explore personal notions of self and nation.

Steve Biko’s, most graphic autopsy pictures have been displayed and extensively printed over a period of twenty years, between 1977 to 1997 and even continue to make periodic appearances in the liberated South Africa in the 21st century. It underwent periods of internal censure, states of emergency, international boycott, and increased collective organisation of anti-apartheid bodies, among other things. In 1994, the nation changed from widespread disenfranchisement to democracy, and a period of concerted reflection was undertaken through the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). Popularly reproduced and artistically appropriated throughout this time, Biko’s postmortem portraits have terrifically extended their meaning beyond that of forensic inquiry. Often they can be read as both an emblem of State abuse and as forceful resistance to it. Sometimes their appropriation affirms the ongoing life of Black Consciousness, the very bedrock of Biko’s identity and the philosophic principles for which he died. Works by five South African artists, the like of Paul Stopforth[51], a self-exiled South African political activist, artist, who emigrated to the United states in 1988, Ezrom Legae[52], a South African sculptor and draughtsman, Sam Nhlengthewa[53], a South African, creative collage artist, Professor Colin Richards[54], a fine artist and academic and David Koloane, considered to have been “an influential artist and writer of the apartheid years” in South Africa. [55], are analysed collectively, in an effort to understand how Biko’s death has affected South Africans’ sense of self and nation during a period of significant violence and political change. It is also to be noted that while Steve Biko was not given the due dignity in death, by the leaking and widespread dissemination of the graphic photographs in the media, of his battered corpse violating the fundamental principles of ethics, the transgression may be justified in exposing how even the white medical profession at the time as well as the so called reputable South African Medical Journal colluded with the apartheid state oppression apparatus to medically cover up the heinous crimes of their masters. This is a serious indictment on the so-called civilized whites in South Africa, who looked upon the “natives” as “barbaric sub-humans”, who could be disposed of like animals, with absolutely no respect for their dignity, nor personal human rights of the Black people. A similar philosophy exists in Israel, against the Palestinians. This policy, is deeply entrenched as a philosophical ideology , even today, not only in white South African, but also in the United States, Britain, France and even in the war-torn Ukraine, where Black South African students were discriminated against, during the evacuation of civilians, following the Russian invasion, at the beginning of the war.

The Bottom Line is that like the death of George Floyd, the South African activist Steve Biko’s death galvanized a global movement against racism. His extrajudicial killing embarrassed Apartheid South Africa on the global stage, much the way Floyd’s death has embarrassed the United States. Although Biko was an activist and George Floyd a citizen, in one crucial way their deaths were quite similar: two Black people whose deaths were contested at the point of inquest and autopsy. Bantu Stephen Biko founded the Black Consciousness Movement in South Africa as a medical student at the University of Natal, Medical School, specifically created by the Nationalist government of South Africa for the training of Black Medical Students, by a decree in 1950, during his brief period of training there, in the suburb of Umbilo, Durban, South Africa.

The answer to God’s rhetorical question becomes timely for those who wrestle with the theodicy of Black suffering and for those who ask how something like the evil of White Supremacy could win and how the death of Steve Biko could have taken place on such a holy night of power in the Islamic calendar? A night God describes as, “better than a thousand months.” We can understand, that on that night it was decreed by divine power, just as the exodus of Moses and the children of Israel from the tyranny of the Pharaoh in Egypt to the promised land, across the sea, for Steve Biko to be martyred. It can also be appreciated, that the All-Powerful divine, began to restrict and control White Power on that night in the angelic realm. It can also be understood that the powerful system of apartheid in South Africa pre 1994, which was thought to be indefatigable was now determined to fail despite being supported by Western powers, including Britain and the United States of America, because surely God is Able. It can be also appreciated that it was decreed that White supremacy’s plot was being undone with exact due measure by the Best of Plotters, the Divine. It can also be understood that Steve Biko’s life on earth reached its pre-destined, decreed time and his blood paid the price for a new era of liberation in South Africa.

It is also interesting to note that followers of the Islamic faith, the Muslims have the privileged opportunity to annually experience both the historic and religiously pivotal night of power, every Ramadan, the fasting month in the Islamic calendar, as well as the night of power, wherein the death of the iconic anti-apartheid activist was caused by the racist white oppressors, like the present day oppressors and killers of Palestinians. The white regime is no more enforcing its supremacy on the majority of the indigenous people of South Africa, whose land they expropriated with the arrival of the first white man, of European descent in 1652. Similarly, the killings and oppression of the indigenous people of Palestine whose land the displaced Jewish people expropriated by British decree will come to an end in the seventh decade as prophesised. Serious concern is expressed by orthodox Jews in Israel, at present, about the future of Israel.

This end of systemic oppression is inevitable, for is cannot be propagated eternally. At the rising of the dawn after Steve Biko was murdered, very few South Africans, let alone the global community, would have believed, way back in 1977, that Steve Biko’s death was actually the death blow to White supremacy in South Africa. In just a decade Nelson Mandela would be freed from prison and elected President of South Africa. Who would have believed you if you had said that last night angels descended as they do annually as decreed to fulfil God’s command to restore justice, so do not fear nor should one grieve. God is undoubtedly able to exact justice over all things. We communally stand and implore God believing that He is surely Able, All Powerful to affirmatively answer, at this pivotal moment in time the rhetorical question: do Black lives matter to God? The answer is an unequivocal yes! Peace shall prevail and in the Divine, humanoids must place their complete trust, for the Pharaonic oppression against the people of Moses, the Roman tyranny against Christendom, the Mongol butchery in Eastern Europe, the tyranny of the Persian Empire, the Colonial oppression in Africa, India and the East, the Nazi epigenetic engineering and quest for world supremacy, are all no more. Surely the bigoted supremacy, as well as the war mongering, of the present-day western powers will be no more, very soon.

_____________________

READ: PART 1 – PART 2 – PART 4

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

25 July 2022

Source: www.transcend.org