By Maria Popova

You know that the price of life is death, that the price of love is loss, and still you watch the golden afternoon light fall on a face you love, knowing that the light will soon fade, knowing that the loving face too will one day fade to indifference or bone, but you love anyway — because life is transient but possible, because love alone bridges the impossible and the eternal.

I think about this and a passage from Louise Erdrich’s 2005 novel The Painted Drum (public library) flits across the sky of my mind:

Life will break you. Nobody can protect you from that, and living alone won’t either, for solitude will also break you with its yearning. You have to love. You have to feel. It is the reason you are here on earth. You are here to risk your heart. You are here to be swallowed up. And when it happens that you are broken, or betrayed, or left, or hurt, or death brushes near, let yourself sit by an apple tree and listen to the apples falling all around you in heaps, wasting their sweetness. Tell yourself that you tasted as many as you could.

This, of course, is what life evolved to be — an aria of affirmation rising like luminous steam from the cold dark silence of an indifferent cosmos that will one day swallow all of it. Every living thing is its singer and its steward — something the poetic paleontologist Loren Eiseley captures with uncommon poignancy in his 1957 essay “The Judgment of the Birds,” found in his altogether magnificent posthumous collection The Star Thrower (public library).

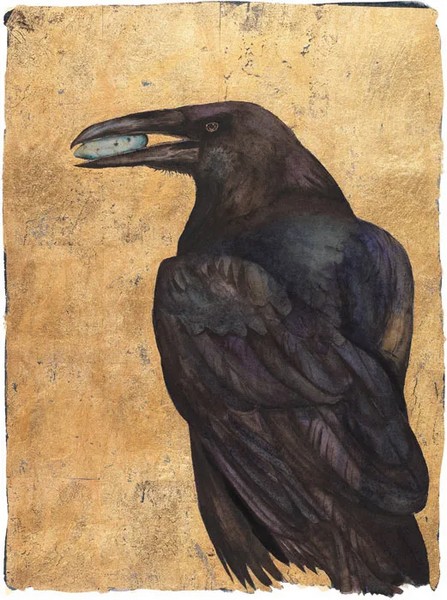

Eiseley recounts resting beneath a tree after a day of trekking through fern and pine needles collecting fossils, dozing off in the warm sunlight, then being suddenly awakened by a great commotion to see “an enormous raven with a red and squirming nestling in his beak” perching on a crooked branch above. He writes:

Into the glade fluttered small birds of half a dozen varieties drawn by the anguished outcries of the tiny parents. No one dared to attack the raven. But they cried there in some instinctive common misery, the bereaved and the unbereaved. The glade filled with their soft rustling and their cries. They fluttered as though to point their wings at the murderer. There was a dim intangible ethic he had violated, that they knew. He was a bird of death. And he, the murderer, the black bird at the heart of life, sat on there, glistening in the common light, formidable, unmoving, unperturbed, untouchable. The sighing died. It was then I saw the judgment. It was the judgment of life against death. I will never see it again so forcefully presented. I will never hear it again in notes so tragically prolonged. For in the midst of protest, they forgot the violence. There, in that clearing, the crystal note of a song sparrow lifted hesitantly in the hush. And finally, after painful fluttering, another took the song, and then another, the song passing from one bird to another, doubtfully at first, as though some evil thing were being slowly forgotten. Till suddenly they took heart and sang from many throats joyously together as birds are known to sing. They sang because life is sweet and sunlight beautiful. They sang under the brooding shadow of the raven. In simple truth they had forgotten the raven, for they were the singers of life, and not of death.

Couple with Hannah Arendt on love and how to live with the fundamental fear of loss, then revisit Loren Eiseley on the warblers and the wonder of being.

My name is Maria Popova — a reader, a wonderer, and a lover of reality who makes sense of the world and herself through the essential inner dialogue that is the act of writing.

1 April 2024

Source: transcend.org