By Dr. Prakash Louis

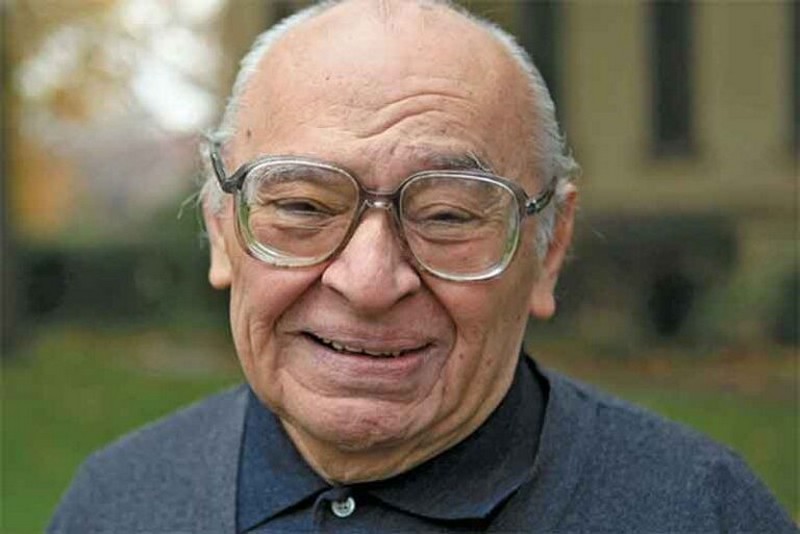

“To know God is to do justice. There is no other way of knowing God.” This statement is from the celebrated liberation theologian, Gustavo Gutierrez who was considered an advocate for the world’s ‘poor and exploited’. Gutierrez a Peruvian Catholic priest promoted ideals that revolutionised the Latin American church. He was regarded as the father of Latin American liberation theology. Homage and tributes are paid to this revolutionary theologian who died on 23rd October, 2024 at the ripe age of 96.Hence, this day is celebrated as a day of the Theology of Liberation. It is significant to note that Aljazeera Media Channel reported about this while the Indian print and electronic media was silent on this.

Gustavo Gutierrez was an eminent Catholic theologian and philosopher, whose book titled ‘A Theology of Liberation’ published in 1971 deeply influenced church doctrine and practice in Latin America. In nutshell the Theology of Liberation as propounded by Gutierrez and later expounded by innumerable theologians and practioners argues that Christian salvation goes beyond spiritual matters, also demanding that people be freed from material or political oppression. He famously wrote: “The future of history belongs to the poor and exploited”. Living among his people, especially the poor and the vulnerable, Gutierrez experienced the joys and sorrows of them. Their life, struggles and simple Christian faith affected him very much.

Gustavo Gutierrez is a Peruvian philosopher, theologian, and priest is often regarded as one of the founding figures of Liberation Theology, a movement that emerged in Latin America in the 20th century. His most influential work, A Theology of Liberation (1971), calls for a Christian approach to addressing poverty and social injustice, framing theological reflection around the lived experiences of the marginalized.

Liberation Theology emphasizes the role of the church in political activism and social justice, arguing that Christian faith requires an active response to inequality. Gutierrez’s ideas have shaped how theology can be applied to promote human rights and social reform, especially in Latin American contexts. His work has been both influential and controversial within the Catholic Church, with supporters championing it as a return to the teachings of Jesus and critics arguing that it overly politicizes the church’s mission.

In this very simple and very straight forward statement, Gutierrez points to the centrality of life and faith of every Christian and all believing human beings. Gutierrez emphasizes that true faith requires active engagement in the fight for justice, particularly on behalf of the poor and marginalized. He in his categorical manner emphasises that this is the only way of knowing God and following Him. If we fail to be engaged in social action for the liberation and emancipation of the poor and the marginalised, then we fail to know and follow Yahweh.

From his experience of the life and suffering of the poor and the vulnerable as a priest of the faithful in Peru in South America, Gustavo Gutierrez attempted theologising from the point of the poor and the oppressed. He placed the suffering of the masses in the hands of the leadership as starting point. Then he examined a spirituality for social commitment springing from the Gospel. Then he addressed the liberation of these suffering people as a project of God and hence of the Church which is made up of believers. He concluded that wherever and whenever there is liberation of the suffering masses, there the Kingdom of God is realised. Hence he asserted, “A spirituality of liberation is the realization of the Kingdom of God in the history of human suffering.”

Thus, Gutierrez reiterated the fact that the Kingdom of God becomes visible in human actions aimed at reducing suffering and advancing justice. He was influenced by these words of Jesus, ‘Truly I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.’ (Mathew 25:40). This is the call placed before all the followers who want to follow Jesus as their own saviour.

Reflecting further on the demand for social commitment for structural change, he argued, “Charity is today a word that has been much abused. True charity, the true love of God, is demanding; it involves actions that confront injustice.” Thus, he challenged the traditional notions of charity, urging Christians to confront the systems that create inequality. Hence, charity as understood from a biblical perspective is not dolling out something to those in need but accompanying them in their struggle for liberation and emancipation.

The centrality of Theology of Liberation could be spelt out in this manner. Gutierrez argues that Christianity must involve active participation in the struggles for social justice, seeing salvation as a holistic transformation, both spiritual and material. He critiques traditional theologies that overlook systemic social issues, arguing that theology should be a practical response to suffering rather than only a theoretical pursuit. One can cull out the following key principles in his work:

- Historical Praxis: Faith and action are inseparable, as Christians are called to engage actively in society and work towards justice and equality.

- Preferential Option for the Poor: Liberation theology asserts that God has a special concern for the marginalized, urging Christians to prioritize the poor in both thought and action.

- Integration of Faith and Social Justice: Spiritual growth is tied to efforts in social reform; social transformation is a path to bringing about God’s Kingdom on Earth. Not just individual transformation but structural change is central to faith.

- Liberation as a Journey: Liberation is not merely political but is also personal and spiritual, encompassing the transformation of relationships, communities, and individuals.

Gutierrez’s work has had significant impact, inspiring movements within the Church, as well as critiques, notably from conservative theologians who felt liberation theology leaned too close to Marxism. Despite controversies, A Theology of Liberation has shaped discussions on social justice within the Church and remains a key text in theological studies.

It is pertinent to note that Gustavo Gutierrez came to develop Liberation Theology through his experiences with poverty and social inequality in Latin America, especially in Peru. His journey toward this theology was influenced by his personal background, educational experiences, and encounters with the harsh realities faced by marginalized communities.

As happens with any prophet, Gutierrez also had to face severe criticism and restrictions from the official church. This came strongly from none other than that time Pope John Paul II. The relationship between Gustavo Gutierrez and Pope John Paul II was complex, shaped by their differing views on the role of the Church in political activism and social justice, especially concerning Liberation Theology. Gutierrez utilised the tools of analysis offered by Marxism to understand the Peruvian and Latin American society, polity, economy and religion. But John Paul II who hailed from Poland was averse to Marxism due to the policies and programs of communists who ruled Poland.

The following were the key points of tension between these two persons:

- Concerns about Marxist Influence: Pope John Paul II was worried that Liberation Theology could lead the Church toward political extremism and potentially compromise its spiritual mission. He saw the emphasis on Marxist analysis within some strands of Liberation Theology as potentially dangerous, especially as he had witnessed firsthand the effects of Communism in his native Poland. He was concerned that the Church’s mission could be jeopardized if it became too aligned with political movements.

- Direct Critiques and Disciplinary Actions: During the 1980s, the Vatican under Pope John Paul II, primarily through Cardinal Joseph Rat zinger (later Pope Benedict XVI), issued critiques of Liberation Theology. Rat zinger, then head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, released documents in 1984 and 1986 that highlighted concerns about Liberation Theology’s use of Marxist elements and warned against what they saw as a reduction of Christian theology to social analysis. Some Liberation theologians faced disciplinary actions, though Gutierrez himself was not formally sanctioned.

- Efforts to Distinguish Orthodox Liberation Theology: Gutierrez and other proponents of Liberation Theology clarified that their theology was grounded in Catholic doctrine, with the intent of reforming oppressive structures in line with Christian values of compassion and justice. Over time, Pope John Paul II’s position became more nuanced, differentiating between Marxist-inspired interpretations and an orthodox Liberation Theology that focused on solidarity with the poor.

But from the time Pope Francis assumed office as the Pontiff, the relationship between Gutierrez and Pope Francis one of mutual respect and shared vision, especially on social issues and the Church’s role in advocating for the poor. Both are deeply aligned in their commitment to justice, dignity, and the “preferential option for the poor.”Francis’s papacy has been marked by a clear and consistent message of solidarity with the marginalized, which is central to liberation theology. He calls for a “poor Church for the poor,” echoing Gutierrez’s vision of a Church deeply involved in the struggle for social justice.

Further, in his encyclicals, particularly Evangelii Gaudium and Laudato Si’, Francis adopts themes familiar to liberation theology, advocating for systemic changes to address poverty, inequality, and environmental destruction.

Francis has broadened the reach of liberation theology’s principles beyond Latin America, incorporating them into the global Church’s mission. His papacy has led to a re-examination of the Church’s role in advocating for structural change to help the poor and protect creation. By adopting a language of liberation theology and promoting grassroots change, Francis has revived and adapted the movement for a global audience, bridging Gutierrez’s theological foundation with the Church’s mission today. Pope Francis’s leadership has brought many of Gutierrez’s ideas to the forefront, renewing the Church’s mission to champion the dignity and rights of all, particularly the vulnerable and marginalized.

Later, the Theology of Liberation was converted into Liberation Theology and spread far and wide. Wherever similar situation of discrimination and injustices based on caste, class, race, gender, environment were found, liberation theology sprang up as a dominant method and mode of theologising. This was also influenced by local culture, religion and traditions. While originally developed in Latin America to address systemic inequalities, liberation theology’s emphasis on a “preferential option for the poor” and social justice resonated with many theologians globally. This was all the more the case in India, Sri Lanka, Africa, South Korea, America, Palestine, etc.

Dalit Theology was one of the most propound outcome of Liberation Theology. Emerging from the Indian context, Dalit theology is a specific expression of liberation theology that focuses on the experiences and struggles of Dalits, historically marginalized communities often referred to as ‘untouchables’ or ‘lower castes’ within the Indian caste system. It addresses the unique forms of oppression faced by Dalits, asserting their dignity and right to equality. Dalit Theology like Liberation Theology does not focus only on the exclusion and exploitation that the Dalits undergo but also searches for the potential for liberation based on social and religious contexts.

Theology of liberation had enormous impact in the evolution of Feminist Theology. Both these are critical theological movements that seek to address issues of justice, inequality, and oppression within the context of Christian faith. While they emerge from different historical and social contexts, they share common goals in advocating for the marginalized and challenging systemic injustices. While Liberation Theology addresses suffering of the masses in general and looks for their emancipation, Feminist Theology focuses on the gender injustice and tries to foreground gender equality and justice.

Theology of Liberation and Tribal Theology are two distinct but related movements that seek to address issues of oppression, marginalization, and social justice within their respective contexts. While Liberation Theology originated in Latin America to address the needs of the poor and oppressed, Tribal Theology emerged in the context of indigenous peoples, particularly in India, focusing on the unique experiences, cultures, and struggles of tribal communities. Tribal Theology focuses on the spiritual and social realities of tribal communities, addressing issues such as displacement, cultural erosion, and social marginalization. It seeks to affirm the identity, rights, and dignity of indigenous peoples, promoting a theology rooted in their experiences and worldviews.

Liberation Theology and Environmental Theology are two distinct yet interconnected movements within Christian thought that focus on addressing social justice and ecological concerns. Both movements critique systemic injustices, but they do so from different angles: liberation theology primarily addresses issues of poverty and oppression, while environmental theology focuses on ecological degradation and the relationship between faith and the environment. Environmental Theology advocates for a responsible stewardship of creation, emphasizing the moral and ethical responsibilities of humans toward the natural world. Going further from this tradition, Pope Francis in his encyclical spoke of “Cry of the earth is the cry of the poor” linking both these as interrelated.

As stated above, Liberation Theology and Black Theology are also movements within Christianity that emerged in the 20th century, focusing on the role of faith in the struggle against social injustice. They prioritize the experiences and struggles of marginalized communities, advocating for societal transformation in line with biblical teachings. Black Theology emerged in the United States during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, reflecting the experiences of African Americans. It centers on the Black experience of oppression, arguing that God sides with the oppressed in their struggle for justice and dignity. From this perspective, Jesus is viewed as a liberator who stands in solidarity with the Black community against racial oppression. Black Theology critiques mainstream Christianity for its historical complicity in slavery, segregation, and racism.

Though Liberation Theology began in Latin America it spread far and wide. This is because, it addressed the life and struggles of common masses who were subjected to oppression and exploitation due to social, economic, political, educational and religious systems. While the starting point of Liberation Theology was the suffering of the poor and the vulnerable but it ultimately sought for their liberation from all forms of oppression. It further emphasized the role of the church in political activism and social justice, arguing that Christian faith requires an active response to inequality.

Gutierrez’s ideas have shaped how theology can be applied to promote human rights and social reform, especially in Latin American contexts. But it is a fact that his Theology of Liberation extended further and inspired theology all over the world. In contrast to many misrepresentations of his thought, he demanded that the faithful see liberation as integral and building individuals and communities so that the Kingdom of God can be realised here and now. One of his most famous statements continue to inspire those who are sincere in following Jesus, “True liberation is not only freedom from oppression but also freedom for life in community and love.” But this thought is counter-posed to those who want to maintain the status quo at all costs.

Dr. Prakash Louis, Director, Xavier Institute of Social Research, Digha-Ashiana Road, Patna, Bihar

28 October 2024

Source: countercurrents.org