By Ida Audeh

One year into the Israel-U.S. genocidal war on Gaza, Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar was killed in combat in Tal al-Sultan in Rafah. For Palestinians (and Arabs generally), he was a man of principle, who spoke clearly and defiantly as he affirmed the right of Palestinians to live free of Israeli domination. Unlike other leaders on a national scale—most recently Hezbollah leader Sheikh Hassan Nasrallah and Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh, among many others—he was not assassinated but rather died in combat, an end for which he had expressed a preference. He commanded the militias that roared out of Gaza on Oct. 7, broke through the structure meant to encage them, neutralized Israel’s southern command, captured prisoners of war and took them to Gaza, to use them as bargaining chips to end the siege on Gaza and to release Palestinians in Israeli prisons. That turned out to be the opening salvo in the Palestinian war of liberation.

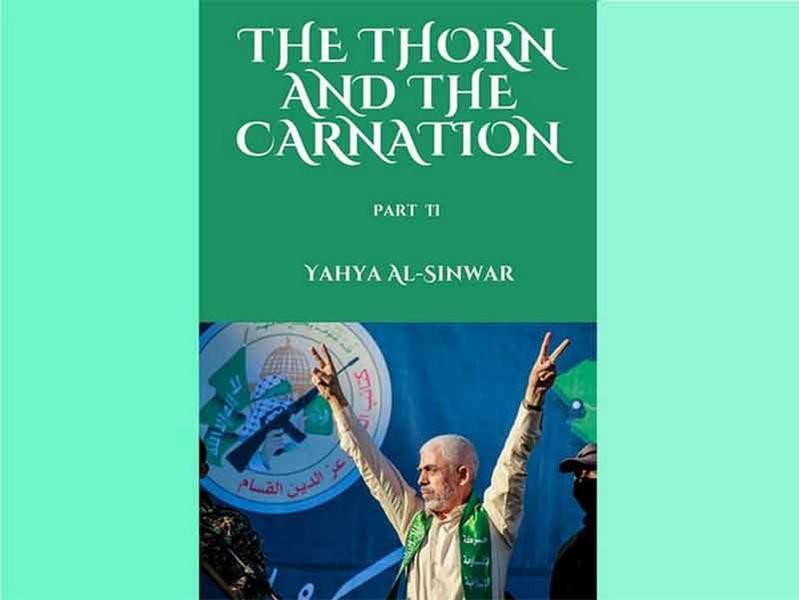

I read Sinwar’s two-part novel, The Thorn and the Carnation, because I hoped that the text might provide some insight into this remarkable man from Gaza whose movement has defied the Israeli-U.S. genocide against the Palestinian people in Gaza, now underway for more than 14 months. Sinwar wrote his novel in prison while serving four life sentences, charged in 1989 with killing two Israeli soldiers and some Palestinian collaborators with Israel. He was 27. He had no way of knowing if or when he would be released (although he might have retained hope that he would be, knowing that the Palestinian resistance never turns its back on its imprisoned cadres), and so he was using the novel to communicate with his countrymen. (As it turned out, he was released in a prisoner exchange in 2011 after serving 22 years of his sentence, an exchange he helped to negotiate.) The novel was completed in 2004, the year Sheikh Ahmad Yassin, founder of Hamas and a wheelchair-bound quadriplegic, was assassinated. For readers today, the ongoing genocide in Gaza provides what amounts to a sequel to the novel; we see a clear trajectory from the events described in the book to the moment we find ourselves in now and that knowledge gives the novel added depth and poignancy.

The novel begins in 1967, when Sinwar’s main character, 5-year-old Ahmad, finds himself living under Israeli occupation; it ends in 2001 or so, during the second intifada. Through the events affecting Ahmad and his impoverished family, Sinwar explores several topics, only a few of which will be mentioned here: direct Israeli occupation and the establishment of the Palestinian Authority (PA); the prison experience; the rise of Islamist activism; the character of the freedom fighter; and the scourge of collaborators.

One senses that Sinwar is attempting to provide a historical record for Gaza’s young population about the brutality of the Israeli occupation: what it was like to live through the Israeli night patrols, the rounding up of men, the extended curfews and the mass destruction of homes in the early 1970s. Gaza was home to a refugee population that needed UNRWA services to survive, but it was also a site of resistance, and neighborhoods developed a system of shouting harmless phrases when Israeli patrols entered their areas without warning, by way of alerting militants to the threat. He describes the discussions that took place when Israel opened its labor market to Gaza. People weighed their need for income against their rejection of interacting with the occupation in any way; practical needs won out, and soon working in Israel was normalized. Sinwar relays this without moral judgment. Years later, the PLO signed the Oslo Accords, and Sinwar portrays the heated arguments between the PA supporter and Islamists within Ahmad’s family. Today the battles raging in Gaza and in the West Bank are the inevitable outcome of that shameful sellout.

The Israeli prison system hovers over the lives of the occupied Palestinians. (It has been estimated that about 40 percent of the male population of the occupied territories has spent time in an Israeli prison between 1967 and 2012.) Sinwar describes the torture methods used in the prisons as well as the practice of using other detainees as informants to extract information in more relaxed conversations in prison spaces. He recounts that by way of explaining the need to remain alert and not let one’s guard down, almost like delivering survival tactics to (young) readers who might find themselves in such situations. The prisons are also sites of political education, organization and resistance, a place where leaders are formed.

Sinwar himself did much more than merely survive in prison—he studied Hebrew and learned it well enough to read biographies of Israeli leaders and to translate text into Arabic. His immersion into the world of Israeli history and biographies made him a match for any Israeli he had to deal with. (Seven months into the current genocide, an Israeli analyst would say, “Sinwar squeezes us like a lemon; he reads the political and military map of Israel better than we do.”)

Today, Israel mass arrests Palestinians and takes them to torture centers, where the extraction of resistance information is of lesser significance than the thrill of torturing Palestinian bodies. In the past, the Israeli population could remain ignorant of the occupation regime’s prisons; but now, Israeli torturers live stream their brutality against Palestinian bodies to sadistic Israeli viewers who clamor for more.

Sinwar’s discussion of student activism offers a fascinating insider’s view of young men charting a political course under conditions of constant threat. Palestinians developed the first university in Gaza when Egypt closed its doors to Palestinian students in the wake of President Anwar Sadat’s normalizing of relations with Israel. Ahmad and his cousin would attend that university, which resembled a high school with a skeletal staff. Several decades later, Gaza could boast 17 higher education institutions, and by mid-April 2024, all of them had been either completely or partially destroyed, and at least 95 professors had been killed, generally with their families. As Israel’s crimes against Palestinians are tallied, add scholasticide to the crimes of genocide and ecocide.

In the novel, Ahmad’s brother Mahmoud is aligned with Fatah; another brother, Mohammad, is an Islamist; and so is Ahmad’s favorite cousin, Ibrahim. Sinwar does not shy away from depicting the criticism of Islamists in the 1970s: that they did not accept the Palestine Liberation Organization as the representative of the Palestinian people (recognition of which had been a hard-fought struggle) and were slow to take up armed struggle. Israel tolerated their early organizing, seeing the Islamist movement as a tool to splinter the Palestinian population into two antagonistic camps. In Part 2, the Islamists are beginning to make their own weapons and attack Israelis wherever they can—mostly soldiers and settlers, but noncombatants as well. Reading the novel in 2024, as the beleaguered Palestinian resistance led by Hamas forges ahead in year two of a battle against Israel financed by the United States—14 months during which it has prevented Israel from achieving a single war objective—one has to marvel at the evolution of the organization. Today it fights with a range of home-made weapons, and its fighters are creating legends. No other liberation struggle—not Algeria or Vietnam or South Africa—has had to struggle against such staggering odds.

While describing the evolution of the Islamist movement, Sinwar depicts the personal characteristics of the ideal revolutionary in the characters of Ahmad’s role models: his brothers and his cousin Ibrahim. Piety is a key ingredient; so are self-sacrifice, discipline and asceticism. Being a good listener and negotiator are necessary for anyone who aspires to lead. Integrity and having an unwavering moral compass are essential qualities. This depiction initially struck me as somewhat idealized. Upon further reflection, I realized that today’s fighters are providing the evidence not only of skill and determination on the battlefield but also of a code of conduct unknown to their enemies.

Western leaders, pundits and the corporate media demonize or dismiss the Palestinian resistance fighters, but many details in the official narrative of “Hamas terrorism” are contradicted by statements of Israelis or the videos taken by the fighters themselves. For example, some Israeli prisoners released in the initial exchange have had positive things to say about their captors—how they were protected by them during times of intense shelling, treated humanely and fed whatever was available to their captors. When they were released to the custody of the Red Cross, they looked relatively relaxed—at least when compared to traumatized Palestinians released from jail who had clearly lost weight and expressed concern for their comrades in prison because of the sadistic torture they were subjected to.

A recent item published on Resistance News Network purports to be a letter from Israeli captive Alexander Trufanov to the Israeli public, in which he expresses fear that his government will kill him or at best, write him off; he says that “the fighters of Islamic Jihad have saved my life several times to keep me from dying. Some of them were wounded, and others lost their lives while trying to protect me.” And this after the fighters’ own family members have been targeted for extermination.

Another example of the principled resistance of the fighters: in the videos released by the resistance groups, we see what they see, including medical evacuations of wounded and dead Israeli soldiers. (Resistance video clips are shown and discussed during the Electronic Intifada’s weekly webcast.) Never do the fighters attempt to impede the evacuations even though they have the Israelis in line of sight. It is truly remarkable, especially when compared with the depraved conduct of Israeli soldiers, executing patients, shooting children in the head, shelling hospitals and raping men and women snatched from the street.

Contending with Palestinian collaborators with Israel is a recurring theme in the novel. As depicted, when evidence of collaboration with the Israeli authorities is confirmed, a social crisis presents itself: the collaborator cannot be allowed to live freely because of the threat he poses to the resistance and to the society at large. In the novel, collaborators were hapless Palestinians who either need movement permits or had committed some moral transgression that made them open to blackmail; today the threat to militants comes from an institution installed to serve the Israeli occupation. Palestinians seethe when learning that PA forces raid refugee camps in search of militants wanted by Israel after these same militants had successfully warded off an Israeli military assault on the camps. Reading the novel as militants in West Bank camps are contending with both Israeli and PA attacks, one understands why Sinwar depicts collaboration with the enemy as a threat that colonized people cannot tolerate.

Yahya Sinwar will be remembered not only for the way he lived his life and the resistance movement he led, but also for the manner in which he met his end: in combat, his head wrapped in a kuffiyeh to hide his identity (he most likely did not want to be captured alive), defiant until the end. Killed by an Israeli soldier who did not recognize him, his body was taken for an autopsy, and the Israelis announced that he hadn’t eaten in three days. That detail, as much as anything he wrote about in his novel, is so characteristic of the man who endured the same hardships as the fighters he led, who described in his novel the lived experience of a nation at the mercy of Israeli-U.S. colonization and who gave his life to the struggle against that brutal regime.

Ida Audeh is senior editor of the Washington Report on Middle East Affairs magazine.

20 December 2024

Source: countercurrents.org