By Harsh Thakor

80 years ago the world witnessed one of the most heroic uprisings in the history of the world. Manifesting the spirit of liberation from tyranny, courage scaled heights almost unparalleled in rebellion of a persecuted community On the eve of Passover 1943 — the nineteenth of April — a group of several hundred poorly armed young Jews lit the spark of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, rising like a phoenix from the Ashes to mark the first insurrections against Nazism. The Jewish uprising in Warsaw testified how people’s organised revolt with Marxist spirit could challenge the most brutal or mightiest of oppressors. It integrated the proletarian Marxist spirit at a helm in regard to liberation of the Jewish community. It expressed the action of a proletarian core, and overall had an electrifying effect on the Polish Resistance.

Quoting Ernest Erber “Only those with a sense of history, with an understanding of the political meaning of resistance to the end, that is to say, the political idealists, choose to fight, not in blind desperation, but to die with a purpose. The heroes of the Ghetto fell with arms in hand because all their Socialist convictions had prepared them for that course of action. Their struggle was not a mere last act of vengeance against the hated enemy. It was a blow for freedom – the Socialist freedom to which they had dedicated their lives.”

For a small group of fighters, realizing that “dying with arms is more beautiful than without,” an isolated group of Jewish militants reminiscent of David confronting the Goliath, resisted for twenty-nine days against a much larger force, aiming to give the most mortal blow to the fascists as they could before they themselves were killed. The uprising, etched into the collective memory of postwar Jewry, lives in people’s minds like an inextinguishable flame

Their heroism was far from being a spontaneous one of the masses, was the product of organisation, planning and preparation from a relatively small — incredibly young — group of Jewish radicals, knitted together in a cohesive force.

Within a few weeks of the Nazi invasion of Poland, Governor Hans Frank ordered four hundred thousand Warsaw Jews to enter a ghetto. By November 1940, around five hundred thousand Jews from across Poland had been entrapped behind its walls, isolated from the outside world and placed in social oblivion.. Surrounded by a ten-foot-high barrier, the creation of the ghetto meant the relocation of approximately 30 percent of Warsaw’s population into 2.6 percent of the city, the designated area being no more than two and a half miles long and having previously housed fewer than 160,000 people.

In the ghetto, Jews were subjected to chronic hunger and poverty. Many families inhabited single rooms, and the dire lack of food meant that roughly one hundred thousand people survived on no more than a single bowl of soup per day. By March 1942 onwards, five thousand people died each month from disease and malnutrition, with entire collapse of sanitation system and breeding of diseases.

The initial response of the Jewish community leadership was passive. Following the creation of the Judenrat Jewish Council) — a collaborationist organization established with Nazi approval to permit easier implementation of anti-Jewish policies — some inhabitants fell into a false sense of security. A predominate idea engulfed the ghetto, examined through the glasses of Jewish history, that Nazism was an inevitable form of persecution that the Jewish people must accept.

Withstanding this demoralization, circles of defiance could be located in the self-organization of the left-wing of the Jewish community. Communists, Socialist-Zionists of varying descriptions, and social democrats organized themselves into sections in the ghetto, aiming to convert the misery into a constructive political organization. All parties — the Bund , a social-democratic mass organization that had enjoyed huge pre-war popularity; the Marxist-Zionist youth group Hashomer Hatzair the left-wing Zionist party Left Poale Zion and the Communist Party dedicated themselves to this strategy, organizing cells that aimed to resurrect collectivist approach among an emotionally battered d Jewish youth.

In dark times, the cell structures of youth organizations built base for combating hunger and depression. “The day I was able to re-establish contact with my group,” wrote the Young Communist militant Dora Goldkorn, “was one of the happiest days in my hard, tragic ghetto life.” In the project to cultivate resistance leadership among the youth, keeping morale high was crucial; acts of friendship such as the sharing of food were as important as distributing anti-Nazi literature.

By 1942, the various youth organizations felt confident enough to establish the formation of an “Anti-Fascist Bloc.” On the insistence of the Communists, a manifesto was drafted that advocated to unite the Jewish left in the Warsaw Ghetto, with the hope of crystallising this political unity across other ghettos.

Calling for a “national front” against the occupation, for the unity of all progressive forces on the basis of common demands and for armed antifascism, the manifesto projected the pre-war Popular Fronts in its organizational methodology.

The Left Poale Zion enthusiastically joined, as did the Hashomer Hatzair — who re-emphasized their fidelity to the Soviet Union, despite the Kremlin’s opposition to Zionism. The Bund, however, were less reliable, due to their historic anticommunism and rejection of specifically Jewish armed action; a party that resolutely stated Poland was the home for Polish Jews, many Bundists refused avenues other than Polish-Jewish unity of action.

The paper of the Anti-Fascist Bloc, Der Ruf, reached publication twice. Its contents placed great accent on upholding Soviet resistance and urging the ghetto inhabitants to accept unconditionally, liberation at the hands of the Red Army.

The bloc’s fighting squads contained militants belonging to all varieties of labour movement groups, but the lynchpin of the organization was Pinkus Kartin A stalwart of communism in prewar Poland and a veteran of the International Brigades to Spain, Kartin was a leader both politically and militarily. It was the arrest and murder of Kartin in June 1943 that culminated the end for the Anti-Fascist Bloc. His arrest ignited an intense repression against the prominent Young Communists, who saw their numbers dwindling and were forced into hiding.

During this period, figures from the right-wing of the Jewish community formed a rival group, the Jewish Military Union (ZZW). Led by the right-wing Zionist group Betar and funded by high society, the ZZW relied upon ex-army officers who could fight orthodox warfare with the Nazis using regular army discipline — unlike the ZOB, which considered itself the armed manifestation of the Jewish workers’ movement..

By contrast, in the eyes of Israel Gutman, the typical ZOB volunteers were “young men in their twenties, Zionists, Communists, socialists — idealists with no battle experience, no military training.” While the propaganda of the ZZW was principally nationalistic, the ZOB’s propaganda and literature propounded antiracist internationalism, offered intellectual positions on the world situation, and debated the labour movement.

Resistance

The ZOB set out to launch an anti-Nazi insurrection. However, it recognized that it was an imperative task in consolidating of the organization’s position in the wider community — it was decided that it had to carry out the intimidation and execution of Jewish collaborators with the occupiers.

For ZOB militants, collaborators represented an auxiliary wing of fascism that was instrumental in facilitating the deportation of Polish Jewry. ZOB militants chose to execute Jewish policeman Jacob Lejkin. For his “dedication” in deporting Jews to Auschwitz, Lejkin was shot, and his example shook the collaborating establishment to its knees.. This was followed by the execution of Alfred Nossig in February 1943. Józef Szeryński, the former head of the ghetto police, committed suicide to avoid his own fate.

These acts ensured ZOB’s vanguard role in the resistance movement, and also sparked resistance from beyond their ranks. In a short period of time they won over many ghetto inhabitants to this position.

Between June and September 1942, three hundred thousand Jews had been deported or murdered. People lost everyone and many young people began to dispense with anxieties about protecting their families and commit instead to militant political activity.

Contempt was shown for the self-determined martyrdom of Adam Czerniakow, the Judenrat leader who committed suicide in July 1942. For young Jewish socialists such as the prominent Bundist Marek Edelman, Czerniakow had “made his death his own private business,” a symbol of privilege in contrast to Edelman and his working-class comrades awaiting their turn on the deportation lists. For them, he said, the overwhelming sentiment in these times was that political leadership necessitated that “one should die with a bang.”

Uprising

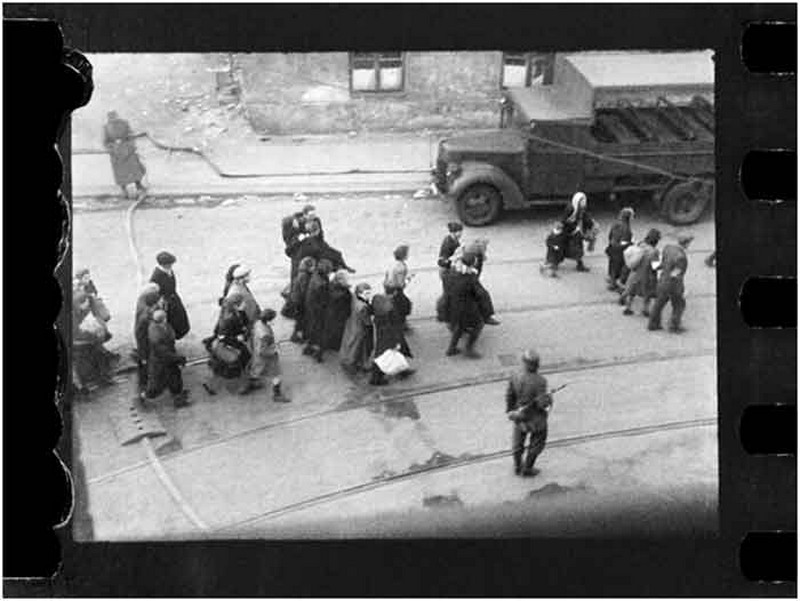

On the morning of Monday, January 18, six months after the first mass deportations of Warsaw Jews (which reduced the number of ghetto inhabitants from four hundred thousand to approximately seventy to eighty thousand), ZOB militants sprouted from the crowds of deportees to attack German soldiers, killing several. A protracted combat followed over four days, where militants infiltrated lines of slave labourers marching towards the Umschlagplatz [Deportation of Jews], stepped out of rank at a given signal, and assassinated their German guards. Though scores of ZOB fighters succumbed, the confusion created by the fighting paved way for some to escape — and demonstrated to others that Nazi bodies were not infallible.

By April 1943, there was a general sensation that the ghetto was to be entirely liquidated. On April 19, five thousand soldiers led by SS general Jürgen Stroop entered the ghetto to remove the final inhabitants; in response, approximately 220 ZOB volunteers spectacularly began their attack, located in ersatz positions in cellars, apartments, and rooftops, each armed with a single pistol and several Molotov cocktails.

The revolt created pandemonium, taking the Nazis by complete surprise and killing many Wehrmacht and SS soldiers. In response, the humiliated German army, suffering losses at the hands of prisoners they thought long vanquished, formulated a policy of systematically burning out the fighters. Intense hand-to-hand combat broke was waged for days, and by late April coordinated warfare by the ZOB collapsed, with the conflict now reaching stage of the Germans burning small groups of armed Jews out of bunker hideouts created to evade capture.

Both the red flag and the blue-and-white flag of the Zionist movement fluttered over ZOB-seized buildings. The youngest fighter killed had been a Bundist activist aged thirteen. Though clearly inexperienced as a fighting force, an anonymously authored Bund internal document that reached London in June 1943 stressed the outstanding political unity and “fraternity” between leftist groups in combat. The relentless dedication to which the young fighters of the ZOB exhibited to their dreams of socialism was manifested to perfection in a May Day rally staged in the scenario of ghetto’s ruins.

The entire world, was celebrating May Day on that day but never in history had the Internationale been sung amist conditions where an entire nation was on the verge of perishing. The words and the song reverberated from the charred ruins portrayed that socialist youth [were] still waging combat in the ghetto, and that even in the face of death they were remained relentless in pursuit of their ideals.

Leading militants of the ZOB committed mass suicide on May 8, surrounded by the German army at their base on Mila 18. By mid-May, the ghetto had been razed, and the Great Synagogue of Warsaw personally blown up by General Stroop on May 16 to celebrate the end of Jewish resistance. A mere forty ZOB combatants had escaped onto the “Aryan” side of Warsaw, where scores more fell before war’s end in the subsequent city-wide uprising of 1944.

Relevance Today

This very spirit of the April 1943 Warsaw ghetto uprising needs to be resurrected with neo-fascism engulfing every corner of our globe, and rising to unparalleled heights. Today in similar light the Palestinians are facing the most perilous conditions. Farmers and workers are facing torments of the worst ever economic crisis, with neo-colonialism enslaving them in another form. Nation chauvinism,Racism,intolerance of religions and victimisation of immigrant communities is rampant, or fervouring at a height, as never earlier. In India, Hindutva saffron fascism is embarking on the same path as the Nazi fascists, stripping the Muslim minorities and dalits of their rights, and political dissent is crushed to dust. Thousands of political prisoners languish within prison walls world over, being denied proper human rights.

Important that the event is not treated with a Zionist tilt but upheld with a Marxist-Leninist perspective.

Harsh Thakor is a freelance journalist who has extensively studied liberation movements.

19 April 2023

Source: countercurrents.org