A Flawed Program – Millions Of Expiring Covid Vaccine Doses: Poorer Na

The short expiration dates of vaccines donated to the sharing program is a major problem, Etleva Kadilli, an official concerned with the issue told the European Parliament (EP) on Thursday. The official heads the Supply Division of UNICEF, the UN’s agency for the betterment of children’s lives worldwide.

“Until we have a better shelf life, this is going to be a pressure point for the countries, specifically when countries want to reach populations in hard-to-reach areas,” she said.

COVAX is currently approaching the delivery of its billionth dose, its management reported. The EU accounts for about a third of the doses delivered to it so far, the official said.

The World Health Organization (WHO), which co-manages COVAX, has repeatedly described the lackluster assistance it received from donors amid the hoarding of vaccines by rich nations as a moral failure.

The program to help poorer nations to vaccinate their populations against Covid-19 is facing a problem, as many donations have a remaining shelf life too short to be properly distributed, a UN official has revealed.

In December alone, over 100 million doses offered to the UN’s COVAX program had to be rejected by aid recipients, most of them due to the looming expiration dates of the vaccines, Etleva Kadilli told the EP.

The agency later in the day said some 15.5 million of the doses rejected last month were reportedly destroyed. Some of the shipments were rejected by multiple countries.

Poorer nations have a number of issues with accepting the vaccines donated to them. Many lack storage capacity to receive shipments and have problems with rolling out vaccination campaigns due to factors like domestic instability and strained healthcare infrastructure.

Some 92 member states missed the WHO’s 40% vaccination goal in 2021 “due to a combination of limited supply going to low-income countries for most of the year and then subsequent vaccines arriving close to expiry and without key parts – like the syringes,” WHO Director-General Tedros Ghebreyesus said during an end-of-year conference in December.

A Flawed Program

Some critics say the program was flawed from the start because it relies on the generosity of the wealthy instead of pushing for wider availability of vaccines to developing nations through the eradication of legal barriers like patent protection. Billionaire Bill Gates, who is an influential figure in global healthcare, has been a vocal opponent of stripping patent protections for medicines, though his foundation seemed to buckle on Covid-19 vaccines after facing criticism over the position.

Alternatives designed for the needs and capabilities of poor nations, like the open-source, patent-free Corbevax vaccine, have been suffering from lack of funding. The vaccine developed by two Texas scientists received more money from the charity arm of spirits maker Tito’s Vodka, which is based in their home state, than from the U.S. government, the project’s co-director Elena Bottazzi told Vice.

A Vodka Maker Gives More Than U.S. Government

The Vice report by Ella Fassler on Jan. 11, 2022 (Open-Source Vaccines Got More Funding From Tito’s Vodka Than the Government, https://www.vice.com/en/article/akvk9j/open-source-vaccines-got-more-funding-from-titos-vodka-than-the-government) said:

With the Omicron variant spreading across the US at an unprecedented speed, medical experts have reignited their calls for mass-producing patent-free COVID-19 vaccines to address the lack of widely-available vaccines in low-income countries. But two scientists in Texas who have successfully developed such a vaccine say their effort still has not received any funding from the world’s richest countries, including the U.S.

Dr. Peter Hotez and Dr. Maria Elena Bottazzi are professors at the Baylor College of Medicine and co-directors of the Texas Children’s Center for Vaccine Development, where they are renewing their pleas for the U.S. federal government and other G7 countries to financially support the mass production of Corbevax, the world’s first open-source, patent-free COVID-19 vaccine being distributed on a mass scale.

Virologists have frequently noted that new variants like Omicron are more likely to emerge in countries where vaccines are not widely available — a problem that vaccine patents exacerbate, and those efforts like Corbevax aim to directly address. Without vaccine equity, low-income nations suffer from the virus disproportionately, all the while increasing the chances that the pandemic will continue indefinitely.

“The U.S. government could, tomorrow, agree to make 4 billion doses of our vaccine,” Hotez told Motherboard. “There is still no roadmap to vaccinating the world. We are doing what we can, but we could do much more if we had help from G7.”

$7 And $1

In July 2021, the U.S. government and Pfizer signed a $3.5 billion dollar contract for the purchase of 500 million doses of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine for international donation to low- and middle-income countries, according to a heavily redacted contract obtained by Knowledge Ecology International, a social justice and transparency oriented non-profit. Each Pfizer/BioNTech dose costs $7, whereas Biological E, an Indian company that has licensed Corbevax, is selling each of its shots for about a dollar.

The doctors helped create what they call the “vaccine for all” with recombinant protein subunit technology, a type of vaccine that has been used to treat hepatitis B for over four decades. Cuba’s Soberana 02, patented by the state-run Finlay Institute, relies on similar technology to combat COVID-19. Lower income countries are able to mass produce recombinant protein vaccines more easily than ones that rely on newer technology, like Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna’s mRNA designs or Johnson & Johnson’s adenovirus vaccine.

And unlike pharmaceutical giants, the Texan center is freely sharing the recipe and know-how with anyone who asks for it — without strings attached — in order to, as they put it, “decolonize,” the vaccine distribution process.

Lives, Not Profit

“Our goal is to save lives, not make a profit,” said Hotez. “We knew that for resource poor settings, there would be a learning curve before you could make enough mRNA or adenovirus vectored vaccines for the 9 billion doses that would likely be needed for Africa, Asia, Latin America. So we right off the bat took a different approach to use the technology that we have used before to partner with vaccine developers in low and middle income countries.”

The Indian government approved Corbevax under an emergency authorization on December 28, following successful clinical trials boasting 90 percent effectiveness against the original COVID-19 strain and 80 percent against Delta. Whether Corbevax is protective against the Omicron variant is unclear. While the current vaccines are still proven effective against severe illness and death, one study conducted by researchers at Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard indicated that the standard regimen of mRNA vaccines do not produce antibodies that neutralize the Omicron variant unless they are accompanied by a booster shot.

Biological E has already produced 150 million doses, anticipates producing 200 million doses per month, and has received an order from the Indian government for 300 million doses. Hotez and Bottazzi expect Indonesia, Bangladesh, Botswana and South Africa to be next in line.

Vaccine Hoarding: U.S. And European Countries

The Vice report said:

Financial support from wealthier countries could accelerate the distribution process. To date, the U.S. and European countries have hoarded vaccines, and pharmaceutical companies and the US government have refused to share the manufacturing know-how and recipes. The World Health Organization and some public health experts have criticized wealthier countries for distributing booster shots to their own citizens before lower-income countries could provide the first two shots to their most vulnerable. As of January 6, just 8.8 percent of people in low-income countries had received at least one dose of a vaccine, compared with 58.8 percent of the world population, according to Our World in Data, a joint project between the University of Oxford and the non-profit Global Change Data Lab.

“If we had even a fraction of the funding that Moderna had gotten, there’s a possibility the world could have been vaccinated by now,” said Hotez. “And nobody would have ever heard of the Omicron variant.”

As of late October 2020, the U.S. government had invested $12 billion dollars in vaccine development as part of Operation Warp Speed. The Texan team invested just $6-7 million total to develop Corbevax, all raised through private donations and one $400,000 grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Bottazzi told Motherboard that her team “constantly” sought government funding “at all levels” in 2020. They made pleas during congressional hearings, webinars, conferences, to journalists, and through op-eds. The philanthropic arm of the Texas-based Tito’s Vodka, which donated $1 million dollars to the effort, has contributed more funds than the U.S. government.

The Great Gates’ Plea: No Open License

The team met also with The Gates Foundation on at least one occasion in the early stages of development, but, Hotez said, they could not engage them either. In 2020, Bill Gates bragged about convincing Oxford University not to release its vaccine under an open license.

“In terms of Operational Warp Speed, it was made pretty clear to us that we were not in the running,” said Hotez. “It was all about supporting and incentivizing the pharma companies, the multinationals and focusing on new technologies, and that was a huge source of frustration for us.”

It is still unclear why Operation Warp Speed prioritized mRNA vaccine designs produced by large pharmaceutical companies over long-standing, cheap, easy-to-produce technologies such as Corbevax. But a likely reason is that mRNA vaccines may be more profitable than other vaccine designs. More than two-thirds of Congress cashed a check from the pharmaceutical industry ahead of the 2020 election, according to Stat News.

Tax filings from 2020 show that Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO), a group that lobbies on behalf of Pfizer, Moderna Johnson & Johnson and other biotech companies, gave $500,000 to Majority Forward, a nonprofit that works to elect Senate Democrats and $250,000 to American Bridge 21st Century, a Democratic fact-checking and research website. One Nation, a GOP-aligned dark-money group, received $250,000 from BIO in 2020.

An earlier public-private collaboration could have played a role in the U.S. government’s investment into Moderna’s vaccine. Prior to the pandemic, Moderna had been working with the NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) on an investigational vaccine for the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, another type of coronavirus. The work “provided a head start for developing a vaccine candidate to protect against COVID-19,” the agency wrote in a news release announcing its clinical trial for Moderna’s vaccine on March 16, 2020.

When the NIH partners with a company to design a drug, its scientists are typically listed as inventors on the patent. This allows the agency and its scientists to earn royalties from sales and potentially gives them the power to allow other companies to license the invention. From 1991 to February 2020, the NIH earned more than 2 billion dollars in royalty revenue from licenses of inventions associated with drugs developed by pharmaceutical companies, according to a Government Accountability Office report.

In 2020, Moderna filed to patent a genetic sequence used in its vaccine without listing NIH as inventors. A bitter dispute between the agency and Moderna resulted, with Moderna ultimately abandoning its application and re-filing another to delay the process.

Moderna has earned billions from the vaccine to date, and the average forecast among analysts for the company’s 2022 revenue jumped 35 percent after President Joe Biden laid out its booster plan in mid-August, according to Marketwatch.

“COVID is just such a massive market. Your market is the entire planet,” James Love, director of the non-governmental organization Knowledge Ecology International, told Motherboard. “And at first, it’s two doses. And then ‘oh, maybe you need to have a booster shot.’ And so there is a third dose, which is what I had. And then maybe it is a special one next year. And then you begin to wonder, ‘where are we going with this?’ If you are talking about doing it with eight billion people, it makes it a pretty big market.”

Public’s Distrust In Large Pharmaceutical Companies

The Vice report said:

Recent studies have shown that the public’s distrust in large pharmaceutical companies has contributed to vaccine hesitancy. As a truly open-source, not-for-profit vaccine, the makers of Corbevax say it could provide people with some sense of security that the shot is actually intended to improve their own health, not boost pharmaceutical profits.

“The mission of our vaccine center, which has been in operation for more than two decades, has always aspired to be open-source,” Bottazzi said. “With the emergency and the pandemic, it’s even better highlighted, the fact that you need new business models for vaccine development that are not just driven by economics. Vaccines, at the end of the day, should be a commodity accessible to all.”

Always The Leftover

A Devex report by Jenny Lei Ravelo and Sara Jerving (‘We will always get the leftovers’: A year in COVID-19 vaccine inequity, December 23, 2021, https://www.devex.com/news/we-will-always-get-the-leftovers-a-year-in-covid-19-vaccine-inequity-102240) said:

More than half of the population in over 60 countries across the world have not yet been vaccinated against COVID-19. The majority of them are in Africa, as well as conflict-affected countries such as Afghanistan and Myanmar, and Pacific island nations such as Papua New Guinea.

“December marks one year since the first doses of the vaccine were administered in rich countries. People in these countries are now onto their third dose while the majority of people in poorer countries haven’t yet even had their first,” UNAIDS Executive Director Winnie Byanyima wrote to Devex. “This is inequality at its harshest.”

The low vaccination rates, mainly due to countries’ limited access to doses, have left lower-income countries largely unprotected as waves of infections have ripped through them.

According to World Health Organization Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, there were enough vaccines produced this year, that if they had been distributed equitably, every country could have reached the 40% target by September.

Instead, as of Dec. 21, 76% of populations in high-income countries were fully or partially vaccinated and only 8.1% were vaccinated in low-income countries, leading to a global outcry against vaccine inequity.

Experts say dose hoarding by high-income countries, export restrictions, manufacturer delays, slow in-country rollouts, and dose donations with short shelf lives have left significant portions of low-income countries’ populations vulnerable to COVID-19. Others also argue that blocked proposals to broaden manufacturing through the voluntary sharing of intellectual property or a temporary waiver of intellectual property have limited countries’ ability to access vaccines.

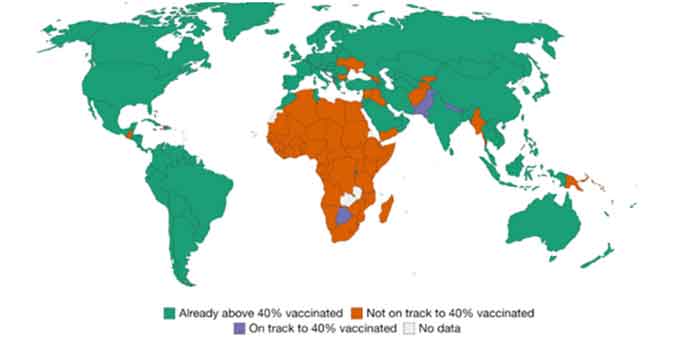

Over 60 countries are not on track to vaccinate 40% of their population by year’s end. Source: Our World in Data

Supply is slated to increase next year, but the introduction of booster shots by high- and middle-income countries, and the threat of new variants, such as omicron, create uncertainties. Getting the vaccines is also not enough — countries need financial, human resources, and technical assistance to ensure doses go from tarmacs to people’s arms.

“Vaccine inequity … is probably the most horrific injustice of 2021. I hope and I pray that it can be improved in 2022,” said Dr. Michael Ryan, executive director of the emergencies program at WHO, during a press briefing Wednesday.

Left To Beg

The report said:

The scene was set for inequity early in the rollouts when higher-income countries hoarded vaccines. This stacked the cards against COVAX, the global COVID-19 vaccine procurement mechanism that aimed to provide equitable access to doses.

It faced financial constraints and challenges in securing supplies, with a lack of commitment from manufacturers and countries engaging in vaccine nationalism, Aurélia Nguyen, managing director of COVAX, wrote to Devex.

It also faced export restrictions. Early on, COVAX relied heavily on AstraZeneca doses produced by the Serum Institute of India. But those supplies quickly dried up when India, dealing with a deadly second wave of COVID-19, imposed vaccine export restrictions that lasted for eight months, leaving many countries, which relied on COVAX, with limited to no access to doses.

It said:

WHO and its partners called on countries that already vaccinated high-risk groups, such as health care workers and the elderly, to donate doses as a stopgap measure. And a handful of higher-income countries responded with pledged doses. As a result, in July, African nations received more doses from COVAX than the months of April to June combined.

But it came at the wrong time after many lives were already lost, Dr. Phionah Atuhebwe, new vaccines introduction officer at WHO Africa, told Devex.

“At a point where we were going through the third wave in Africa and had completely no doses, the richer countries were rushing to vaccinate even their teenagers, when health care workers in Africa were working in COVID treatment centers, unvaccinated. They knew it. We were in the news. We were making all of these noises. We were literally begging,” she said.

But even with an increase in donated doses delivered, countries are still behind on their pledged doses. Of the over 1.5 billion doses pledged to COVAX through next year, only 378 million doses were delivered as of Dec. 21. That’s part of COVAX’s total deliveries to date of about 806 million doses, which is still 300 million doses short of the 1.1 billion doses it expected to deliver by the end of this year when it announced its revised supply forecast in September.

COVAX has been pummeled with criticism for key decisions made along the way. Nguyen said in planning for future pandemics, contingency financing and a geographically distributed manufacturing base for vaccines, especially in emerging markets, should be a priority. But as supply becomes relatively stable, it will also be important to ensure countries get the support they need to grow their capacities to absorb and deliver doses, she said.

More than 1 billion doses of countries’ donation pledges to COVAX have yet to be delivered. Click here for a larger version of the image.

‘Profit First, People Second’

The report said:

Now, even with adequate levels of supply, many countries are struggling to roll out vaccines.

“People in big city centers, big towns have really accessed these vaccines. But then people in rural areas, where a health facility is a couple of kilometers away, are not able to access these vaccines,” said Elizabeth Ntonjira, global communications director at Amref Health Africa.

A key hurdle is the donation of vaccines with short shelf lives. COVAX has struggled with receiving detailed information from vaccine manufacturers and donor governments about vaccine deliveries, making it difficult for countries to plan rollouts.

“Even when you have a nice, smoothly running program — the moment you get short shelf life vaccines, everything is thrown into tatters and you have to rush and quickly deploy these vaccines throughout the country,” Ntonjira said.

High-income countries donating doses near expiry, while opposing proposals to waive intellectual property on COVID-19 vaccine production is like “offering crumbs off the table while banning hungry people from using the recipe to bake their own bread,” said Byanyima, citing similarities to the AIDS epidemic. It took a decade, and the death of 12 million Africans before antiretroviral medicines became more accessible in lower-income countries, she said.

“This profit-first, people-second, strategy has given us a world in which just 3% of people in low-income countries are fully vaccinated: The ideal breeding ground for new virus variants,” said the UNAIDS chief.

“Let me be as explicit as possible: Leaving people in poor countries unvaccinated will also cost the lives of people in the richest countries,” she added.

Precarious Supplies

It said:

It is been a year of missed targets. Many countries failed to meet WHO’s goal to vaccinate 10% of populations by September and at least 35 countries have yet to reach this target as of Dec. 21. And at the current pace, WHO estimates the African continent won’t reach an average of 40% of populations fully vaccinated until May 2022.

Forty-eight countries are not on track to meet WHO target to vaccinate 70% of their population by the end of June 2022. In fact, the African continent isn’t expected to vaccinate an average of 70% of its population until August 2024.

Several experts predict supply constraints will start to ease next year. Airfinity, a global health intelligence and analytics company, forecasts production of 8.6 billion doses during the first half of 2022, reaching a total of 19.8 billion doses by the end of June, at current rates of production. But if half of that production shifts to producing a vaccine targeted toward omicron, the total vaccine production forecast could drop to 16.4 billion doses.

Australia, India, Japan, and the U.S. are reportedly on track to produce at least one billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines by the end of 2022. The bulk of high-income countries’ pledged dose donations is also planned for next year. Other vaccines, including those produced by Novavax and Clover Biopharmaceuticals, are expected to become available. Nguyen said COVAX and partners must work with countries to prepare them for introducing these new vaccines.

”In theory, there are enough doses for everyone. It is a case of prioritizing supply to Africa and of course, supporting African countries to accelerate their vaccine programs,” Atuhebwe said.

Supplies, and support to deliver doses are also needed in conflict-affected countries and displaced populations within countries. A few organizations have already applied for doses via COVAX’s Humanitarian Buffer, but majority of vaccine makers’ reluctance to waive legal indemnity requirements — meaning governments or humanitarian organizations receiving the vaccines for distribution to assume liability for any injury claims by those who received the shot — has posed challenges for vaccine distribution via the buffer.

So far only Johnson & Johnson, and Chinese vaccine manufacturers Sinopharm, Sinovac, and Clover have agreed to waive the indemnification requirements for humanitarian agencies delivering the vaccines to these vulnerable populations. The first deliveries via the buffer took place just last month to reach displaced populations in Iran, including Afghan asylum-seekers and migrants, and another batch is slated for migrants and refugees in Thailand. Both deliveries are expected to vaccinate almost 800,000 people.

But these supplies could face constraints as a number of countries accelerate their booster programs. Over 461 million booster shots have been administered as of Dec. 22, more than the total vaccines administered in Africa. Each day, about 20% of all administered doses globally are boosters or additional doses, which WHO defines as a vaccine that “may be needed as part of an extended primary series for target populations where the immune response rate following the standard primary series is deemed insufficient.”

“I know that we will always get the leftovers,” she added. “If the shoes changed, if we changed places, I know Africa would do more for the Western world than they did for us.”

Source countercurrents.org