By John Feffer

The last near-century of American dominance was extraordinarily violent. Is it coming to an end?

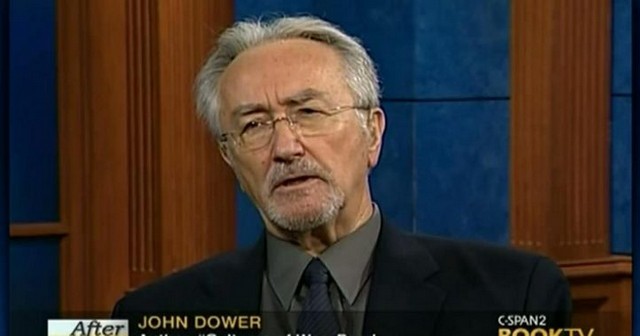

30 Jun 2017 – John Dower is one the most preeminent historians of World War II’s Pacific theater and the aftermath of the conflict in Asia. His book War Without Mercy (1986) described the racial component of the U.S. campaign against Japan. In Embracing Defeat (1999), he examined the post-war U.S. occupation of Japan. He has long taken a critical look at U.S. foreign policy, subjecting the vaunted ideals of America’s global pretensions to skeptical scrutiny. He’s not interested in “good wars” or “good occupations.” He describes the exercise of power, and it’s almost never a pretty picture.

In recent years, Dower has been extending his critical analysis both chronologically and geographically. Cultures of War (2010) was an initial effort to link the violence of World War II to 9/11 and the Iraq War. Now, with The Violent American Century, Dower deepens his analysis by addressing the emergence and expansion of American global power all the way up to the Obama era. Dower is particularly interested in connecting the dots between the United States that emerged victorious from World War II and the America of the 21st century that appears willing to do almost anything to maintain its status as the world’s only superpower.

Dower begins his story just at the moment when the United States is poised to become a global titan. It’s 1941, the year the United States officially entered World War II. It’s also when Time’s Henry Luce proclaimed the beginning of “the American century.” For all his talk of democratic principles and the American spirit, Luce was not naïve. He knew that America would have to use force – in some cases, overwhelming force – to establish its global position. The saturation bombing of Dresden and Tokyo followed by the nuclear attacks against Nagasaki and Hiroshima became the pivotal moments of “war and terror” on which the United States would secure its authority.

Dower traces the impact of America’s nuclear policy from Hiroshima to the present, explaining how the “balance of terror” served a key role in cementing U.S. status. He discerns in U.S. indifference to human rights considerations during the Cold War – with the exception of the first two years of the Carter administration – the origins of later torture policy in the post-9/11 era. Certainly successive administrations in Washington introduced innovations in the maintenance and control of U.S. global influence, such as extraordinary rendition, drones, and enhanced surveillance capabilities, but many of the features of the “violent American century” were present at the creation.

And that’s Dower’s point. He is writing against a

chorus of detached observers who argue that violence has been contained compared to the horrors of World War Two and earlier times – and that even the death, pain, and agony we have seen since September 11 actually reflects, on the part of the United States, a praiseworthy technological and psychological turn in the direction of precision, restraint, and concern with avoiding civilian casualties.

Quite the contrary: the United States, Dower argues, may have refined its techniques, but it has done nothing to minimize the brutality. The casualties of the Iraq War alone – which number in the hundreds of thousands – undermine any notion that the United States had become a kinder, gentler superpower.

By 2016, the “American century” was only three-quarters complete. Dower brilliantly describes the infancy, adolescence, and working years of U.S. global dominance. He spends less time exploring the slowing down of the U.S. war machine during the period of international instability the Obama administration experienced. And he doesn’t speculate much on what will happen with America’s global power during what might very well be its dotage.

True, the United States seems unlikely to retire from the international stage as the American century passes the 75-year mark. But the election of Donald Trump does appear to herald a kind of second infancy, as the new president toddles about the world stage, promises to use force without restraint, and makes the most elemental of errors.

Even without Trump, whose election came after the completion of Dower’s book in September 2016, the United States was showing the strain of its “long war” against terrorism, its military bases and operations in more than 100 countries around the world, and the opportunity costs for American infrastructure and American lives at home. The obvious question, which Dower doesn’t ask or answer, is: what comes next?

China has proposed its own dream of power and prosperity. Many Russians would like to put together a Eurasian century. The European Union vacillates between disintegration and a larger global role for itself. The global South – India, South Africa, Brazil – is tired of the arrogance of the global North.

Will these aspirants to global power necessarily adopt comparable policies of war and terror to displace the United States and maintain their new status? That’s not part of Dower’s remit. But however brutal the century that follows the “American century,” you can be sure that the new hegemons will use the same language of virtue and restraint as the United States has done, even as they engage in abuses both large and small.

John Feffer is the director of Foreign Policy In Focus and the author of the dystopian novel Splinterlands.

10 July 2017