By Patrick Lawrence

27 Nov 2022 – Among our mentally impaired president’s more prominent campaign pledges during the 2020 political campaigns was that his national security people would negotiate America’s return to the multi-sided accord governing Iran’s nuclear programs. Without hesitation, I offered excellent odds that this would stand tall in Joe Biden’s forest of broken promises. It was a wager I truly did not want to win.

And now it seems I have.

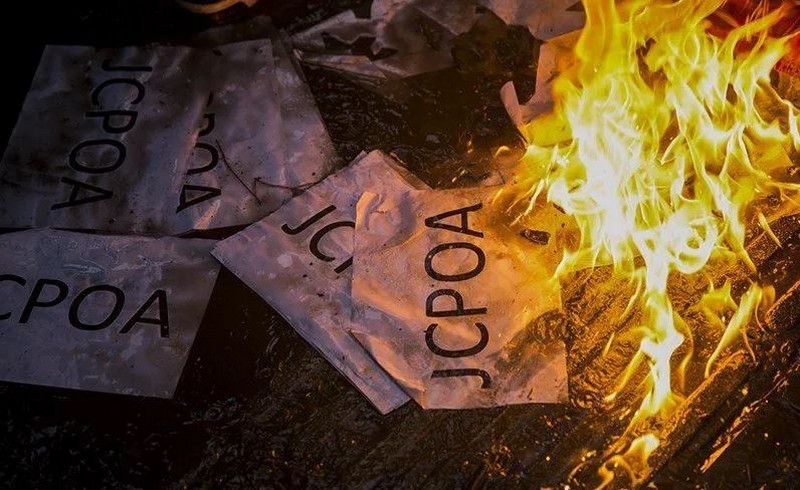

Events over the past several weeks, in the U.S. and in Israel, indicate strongly that the Biden administration has decided to drop all notion of reviving the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, the JCPOA, as the 2015 agreement is called. In effect, Biden will hold to the position Donald Trump took when he pulled the U.S. out of the pact in 2018.

This brings us straight back to those dangerous years when recklessly risky covert operations in the Islamic Republic and the threat of open conflict were the norm. But what is a little more existential peril when Washington is all but directly confronting the world’s most heavily nuclearized nation by way of a wildly irresponsible regime located on Russia’s doorstep? I suppose we can look at it this way.

I knew all along I had made a safe bet on the fate of the Iran accord. Given the way Biden has operated over his half-century career, if he says he is going to do something it is a fairly good sign he has no intention of doing it. And there seemed to me no way an American pol so deep in the Israelis’ pocket would take any step that would displease the apartheid state’s savagely anti–Iran leadership.

This is a man who famously proclaims “You need not be a Jew to be a Zionist”—an assertion of his position he repeated during a state visit to Israel but four months ago. This is also a man who long ago learned how to manipulate Capitol Hill politics to his own advantage.

I know it is asking a lot, but readers may cast their minds far, far back to the forgotten days of “Build Back Better,” the second coming of FDR, and all that. It seemed perfectly obvious that Biden knew he could make all the extravagant promises he thought politically expedient because he also knew few to none of them would ever make it through the houses of Congress.

It was the same with the idea of bringing the U.S. back into the JCPOA. The lying dog-faced pony soldier who moved into the White House in January 2021 knew he could commit to reviving the accord with no chance his administration would ever do so. As soon as Biden assumed office and named his national security detail it was perfectly evident that Israel would be running their Iran policy.

Bibi Netanyahu was prime minister at the time, readers will recall, and he made it explicitly clear on repeated occasions during Biden’s early months in office that his Israel would never accept a restored or even renegotiated JCPOA. From then onward, the fate of the accord has been color by number.

The U.S. went ahead with new talks with the Islamic Republic, beginning in April 2021 and continuing well into this year. These were conducted indirectly in a Geneva hotel, with European diplomats running room to room as go-betweens. The American negotiators were led by Robert Malley, a seasoned conflict-resolution man with a pretty good record.

Details of just what was in the new accord—what of the original limits on Iran’s nuclear development, what was added to them—were never made clear. Iran’s preoccupation during the Geneva talks was with a guarantee that sanctions relief it would receive in exchange for its concessions would not be withdrawn when one Washington administration gave way to another—Tehran having taken the Trump withdrawal as a stinging betrayal.

Josep Borrell, the European Union’s foreign policy director, announced last August that he had in hand what he described as a draft of a final agreement to restore the JCPOA. “What can be negotiated has been negotiated,” the Spanish bureaucrat declared. For a short while after that I began to worry I might lose my money: Maybe they would pull this off after all.

No chance. On August 24, a couple of weeks after the Borrell announcement, the bubble burst. Ned Price, the State Department spokesman, stated—deadpan, no detail—that the U.S. had sent a response to the draft Borrell was waving around. John Kirby then signaled that the U.S. would keep a safe distance from it. “Gaps remain,” Biden’s “strategic communications” man declared. “We’re not there yet.”

And then came Israeli PM Yair Lapid, who, like Netanyahu, is of the right-wing Likud party. “A bad deal,” he said of the draft. The diplomats in Geneva “must stop and say ‘Enough.’” The new outline “does not meet the standards set by Biden himself, preventing Iran from becoming a nuclear state.”

Note the language of a leader whose nation was party neither to the original agreement nor to the new negotiations: To his mind, what would constitute a good deal could not be limited to banning a nuclear weapons program; Israel would insist Iran must not have a nuclear program of any kind, even one limited to peaceful purposes—energy production, advanced medical procedures, and the like. Three months later, nearly to the day, we read this David Sanger piece published in Sunday’s New York Times:

“Now, President Biden’s hope of re-entering the United States into the deal with Iran that was struck in 2015, and that Donald J. Trump abandoned, has all but died…. At the White House, national security meetings on Iran are devoted less to negotiation strategy and more to how to undermine Iran’s nuclear plans, provide communications gear to protesters and interrupt the supply chain of weapons to Russia, according to several administration officials…. ‘There is no diplomacy right now under way with respect to the Iran deal,’ John Kirby, a spokesman for the National Security Council at the White House, bluntly told Voice of America last month.”

Sanger, who has followed the Iran question for many years and who consistently reflects the national security state’s perspective, asserts, “A new era of direct confrontation with Iran has burst into the open.”

In the Iran context, “direct confrontation,” should readers need reminding, is a phrase weighing roughly the same as one of those F–35 jets the U.S. sells to the Israeli Defense Forces.

Sanger’s piece explains what is supposed to be an abrupt turn away from the JCPOA talks by noting the Tehran government’s tough responses to recent protests in the capital and other cities, Iran’s sales of drones to Russia, and violations of Iraqi territory—yes, believe it, the U.S. gets very upset when it hears of violations of Iraqi territory. Most worrisome, it seems, is that Iran intends to enrich uranium to “near bomb grade”—not bomb grade—at a facility called Fordow that is built inside a mountain.

The problem with Fordow, Sanger writes, is that it is “hard to bomb.” I am reminded of a remark Netanyahu made in response to Iran’s development of missile defense systems a few years ago. These will make it hard for us to attack, Bibi complained. How dare those Iranians.

To be clear about these matters, the recent unrest in Iran is three things: justified, unfortunate given the official repression it prompts, and none of the Biden administration’s business if you subscribe, as I do, to the principle of nonintervention in the internal affairs of other nations. Iran’s drone sales to Russia reflect the steady elaboration of the bilateral relationship and simply do not hold up as an excuse to shut down the Geneva diplomatic process.

As to Iran’s enrichment programs, we’ve been around this any-moment-they-will-build-a-bomb bit for too many years to count. Far down in Sanger’s piece, where this stuff always appears, we read, “The United States recently issued an assessment that it had no evidence of a bomb-making project underway.” I love Sanger’s comeback after writing that obligatory sentence: But maybe the intelligence is wrong, he suggests.

Nowhere in Sanger’s report—as nowhere in all mainstream reporting, indeed—do we read that Iran condemns nuclear weapons as a matter of religious principle and national defense doctrine. Just a small matter of no particular account.

My take on Iran’s nuclear intentions, for the record, remains what is has been for many years: The Islamic Republic has no ambition to build a nuclear bomb but would find it a useful deterrent—and who wouldn’t with Israel next door?—were it to develop the capacity to build one.

The Biden administration has all along had to give the appearance of a genuine effort in Geneva, and maybe Malley’s work was so. But it is the same, again, as with Build Back Better: We tried to give Americans what they want and need, but Congress blocked us. In the Iran case, after months of diplomatic footsie, the recent developments David Sanger cited presented a convenient out: We tried to negotiate with these people, but then… and then… and then…

The timing of this turn in the administration’s public presentation of its Iran policy merits brief attention. Israel’s legislative elections earlier this month have opened the way for Netanyahu, still obsessed with attacking Iran, to return to power. As none other than Tom Friedman noted in “The Israel We Knew Is Gone,” the new government he appears likely to head will be an absolute freak show—“a rowdy alliance of ultra–Orthodox leaders and ultranationalist politicians, including some outright racist, anti–Arab Jewish extremists once deemed completely outside the norms and boundaries of Israeli politics.”

It is impossible to imagine—or I find it impossible, anyway—that the Biden administration’s decision to abandon negotiations on the Iran nuclear accord, apparently promising only a few months ago, is not primarily a reflection of this turn in Israeli politics.

Americans and Israelis have already trained for an attack on Iran’s nuclear facilities. Ehud Barack, a former Israeli defense minister, let it be known years ago that Netanyahu planned military strikes on three occasions—2010, 2011, and 2012—but was foiled by inopportune circumstances or reluctant officers.

The JCPOA talks in Geneva, apart from their stated intent, represented an open channel between Washington and Tehran. I recall John Kerry, Obama’s secretary of state, declaring after the accord was signed in mid–July 2015 that it was a door through which other matters could be addressed.

What will come now, as the Biden administration closes this door? To watch and pray is all I can think to do.

Patrick Lawrence, a correspondent abroad for many years, chiefly for the International Herald Tribune, is a columnist, essayist, author and lecturer.

28 November 2022

Source: www.transcend.org