By Maria Popova

“Love the earth and sun and the animals,” Walt Whitman wrote in his timeless advice on living a vibrant and rewarding life — advice anchored, like his poetry, in that all-enveloping totality of goodwill that makes life worth living, advice at the heart of which is the act of unselfing; poetry largely inspired by the prose of Emerson, who had written of the “secret sympathy which connects men to all the animals, and to all the inanimate world around him.”

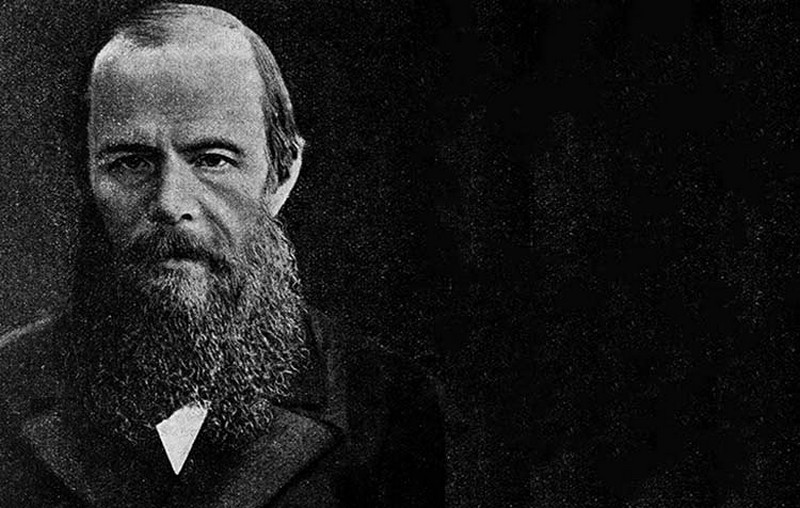

A quarter century after Leaves of Grass, Fyodor Dostoyevsky (November 11, 1821–February 9, 1881) took up this bright urgency in his final novel, The Brothers Karamazov (public library | public domain) — one of the great moral masterworks in the history of literature.

Dostoyevsky — who felt deeply the throes of personal love — contours the largest meaning of love:

Love every leaf… Love the animals, love the plants, love everything. If you love everything, you will perceive the divine mystery in things. Once you have perceived it, you will begin to comprehend it better every day, and you will come at last to love the world with an all-embracing love. Love the animals: God has given them the rudiments of thought and untroubled joy. So do not trouble it, do not harass them, do not deprive them of their joy, do not go against God’s intent. Man, do not exalt yourself above the animals: they are without sin, while you in your majesty defile the earth by your appearance on it, and you leave the traces of your defilement behind you — alas, this is true of almost every one of us!

In our era of ecological collapse, as we reckon with what it means to pay reparations to our home planet, the next passage rings with especial poignancy, painting the antidote to the indifference that got us where we are:

My young brother asked even the birds to forgive him. It may sound absurd, but it is right none the less, for everything, like the ocean, flows and enters into contact with everything else: touch one place, and you set up a movement at the other end of the world. It may be senseless to beg forgiveness of the birds, but, then, it would be easier for the birds, and for the child, and for every animal if you were yourself more pleasant than you are now. Everything is like an ocean, I tell you. Then you would pray to the birds, too, consumed by a universal love, as though in ecstasy, and ask that they, too, should forgive your sin. Treasure this ecstasy, however absurd people may think it.

Complement with Shelley’s prescient case for animal rights and Christopher Hitchens on the lesser appreciated moral of Orwell’s Animal Farm, then revisit Dostoyevsky, just after his death sentence was repealed, on the meaning of life.

My name is Maria Popova — a reader, a wonderer, and a lover of reality who makes sense of the world and herself through the essential inner dialogue that is the act of writing.

28 August 2023

Source: transcend.org