By Binu Mathew

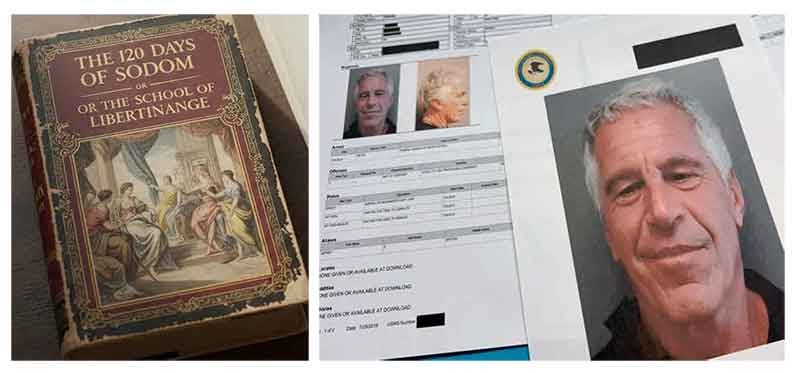

I still remember the unease that first crept into me as a young man when I encountered The 120 Days of Sodom by Marquis de Sade. It was not merely shock—it was a deep, unsettling recognition of something profoundly disturbing in the human condition. Yet, like many readers, I comforted myself with a convenient thought: this is only fantasy, an exaggerated descent into depravity that could never find real expression in the world outside the page.

De Sade’s unfinished novel, written in 1785 while he was imprisoned in the Bastille, is structured with chilling precision. Four wealthy libertines—a duke, a bishop, a judge, and a financier—retreat into an isolated chateau, accompanied by a group of abducted boys and girls. Over 120 days, they subject their captives to escalating cycles of sexual violence, humiliation, and torture, catalogued with bureaucratic detachment. The narrative is less a story than a system—an inventory of cruelty.

The historical context matters. De Sade wrote on the eve of the French Revolution, in a society where aristocratic privilege had reached grotesque extremes. His work is often read as both a product and a critique of that world—a savage allegory of power unrestrained by morality. The libertines are not aberrations; they are the logical outcome of a system that places absolute authority in the hands of the elite. Unsurprisingly, the novel was suppressed for decades, circulated clandestinely, and later condemned as obscene, immoral, and dangerous. Even today, it remains one of the most controversial works in literary history.

Years later, in 1996, at the International Film Festival of Kerala (IFFK) held in Kozhikode, I watched Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom. If the novel had disturbed me, the film was almost unbearable. I remember the atmosphere in the theatre—tense, uneasy. As the scenes unfolded, many around me could not endure it. People stood up and walked out, unable to confront the relentless degradation on screen.

Pasolini’s adaptation transposes de Sade’s narrative to the final days of Mussolini’s fascist regime in the Italian Social Republic of Salò. The libertines become fascist officials, and the château becomes a sealed space of totalitarian power. The film strips away any illusion of distance. It is stark, clinical, and merciless in its depiction of abuse. Pasolini’s political intent is unmistakable: fascism is not merely a political system but a structure that commodifies and destroys human bodies. Power, in its absolute form, becomes indistinguishable from sadism.

The reception of Salò mirrored the outrage that greeted de Sade’s work. It was banned in several countries, condemned by critics, and remains one of the most controversial films ever made. Yet, like the novel, it endures because it forces us to confront an uncomfortable question: what happens when power operates without accountability?

For a long time, I held on to a fragile belief—that such horrors belonged to fiction, to allegory, to the darkest corners of imagination or history. I wanted to believe that the world had moved beyond such barbarity.

Then came the Epstein story.

What shattered me was not just the scale of the abuse but the banality of its setting. Jeffrey Epstein did not operate in a remote château hidden from the world. He moved in the highest circles of global power—among billionaires, politicians, royalty, and celebrities. His crimes were not the product of isolation but of access. Young girls were trafficked, abused, and silenced within a network that intersected with the very structures meant to uphold justice.

Names began to surface—figures linked, questioned, or scrutinized in connection with Epstein’s world: Bill Clinton, Prince Andrew, Donald Trump, among others. Whether through association, allegation, or documented interaction, the proximity of power to abuse became impossible to ignore. This was not a fictional circle of libertines; this was the real elite.

In many ways, the Epstein case is more horrifying than de Sade’s novel. De Sade imagined a closed system where cruelty could flourish unchecked. Epstein’s reality reveals something far more disturbing: such cruelty can exist within open society, shielded by wealth, influence, and institutional complicity. The libertines of Sodom needed isolation to carry out their crimes. Epstein did not.

De Sade’s work was a warning—a grotesque exaggeration meant to expose the moral decay of a privileged class. Pasolini amplified that warning, linking it to the machinery of fascism. But Epstein shows us that the warning was not heeded. The same dynamics—power without accountability, bodies reduced to objects, systems that protect perpetrators—persist, not in fiction, but in our lived reality.

If anything, Epstein mirrors the moral corruption of modern elites with a clarity that de Sade could only imagine. The structures have changed, the language has softened, the settings have become more discreet—but the underlying logic remains the same. Power shields itself. Wealth silences victims. Justice bends.

I can no longer take comfort in the idea that such horrors are confined to novels or films. The distance between fiction and reality has collapsed.

And that is why the Epstein files matter.

Every name, every letter, every video, every fragment of evidence must be pursued with uncompromising rigor. This is not about spectacle or scandal; it is about accountability. It is about dismantling the networks that enable such crimes and ensuring that no individual—no matter how powerful—is beyond the reach of the law.

Justice, in this case, cannot be partial or selective. It must be complete.

For the victims, whose suffering has too often been dismissed or ignored, anything less would be another form of betrayal.

Binu Mathew is the Editor of Countercurrents.org. He can be reached at editor@countercurrents.org

18 February 2026

Source: countercurrents.org