By Martin Jacques

In these Covid times, “There is an ongoing attempt to reframe G7 as the representative and champion of the democratic world in the struggle against autocracy, shorthand for China…. West’s indifference to the vaccination needs of the developing world will be on full display at the G7 summit”.

***

Fine words will accompany the G7 summit this week. Much will be promised. And little will be delivered. It has long been like this. The G7 is no longer fit for purpose. Comprising the US, UK, Germany, France, Italy, Canada and Japan, in the 1970s the G7 was the overlord of the global economy. Today, the G7 is but a pale shadow of what it once was, reduced to the role of a declining faction within the global economy. It still talks in grandiose terms about its intentions, but the world has learnt to discount them. It is entirely appropriate that this week’s summit will be chaired by UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson, a grandmaster of verbal exaggeration and empty gestures.

The role and importance of the G7 has been greatly diminished by the rise of the developing world. The latter now accounts for almost two-thirds of the global economy compared with one-third by the West: in the 1970s, it was exactly the opposite, the West enjoying a two-third share and the developing world just one-third. The most dramatic illustration of the G7’s waning authority came in 2008 when, at the height of the financial crisis, it was effectively displaced by the more representative G20.

Ever since, the G7 has increasingly become an institution in search of a role. Under Biden, as if to confirm its eclipse as a global institution, there is an ongoing attempt to reframe G7 as the representative and champion of the democratic world in the struggle against autocracy, shorthand for China. To this end, South Korea, India, Australia and South Africa have been invited to attend the G7 summit this week. There is even talk of the G7 becoming the D10 (D being a reference to democracy). This, however, would only serve to emphasize the declining authority of the G7: from global leader to ideological sect.

The truth, however, is that this proposal is unlikely to gain assent either among existing G7 members or potential new members, excepting perhaps Australia. Here we get to the heart of the crisis of the G7. It is the rise of China, above all else, that has transformed the global economy, sidelined the G7 and, at the same time, reconfigured the various G7 economies.

Good relations with China are fundamental to the economic prospects of Germany, France and Italy. That is why they are opposed to the G7 becoming an anti-China crusade. So is Japan; and likewise would-be recruits such as South Korea and South Africa. Here laid bare, then, are the fault lines of the G7 and any potential extended membership.

The West is divided and fragmenting. The authority of the US is in decline, no longer able to get its way as it once was.

The best illustration of the growing impotence of the G7 concerns its relationship with the developing world. For eight years, the West has been trying to find a way of responding to the China-proposed Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The subject is due to be raised again at this week’s G7 summit.

All the ideas that have been offered as a basis of a Western alternative to BRI have come to nought. This failure is extraordinarily significant and most revealing about the West on the one hand and China on the other.

BRI is an eloquent articulation of China’s relationship with the developing world, rooted in its own semi-colonial past and its position as a developing country.

The West, in contrast, has failed because its history has been precisely the opposite, one of colonization and the exploitation and subjugation of these countries. It has neither the experience, empathy nor motivation that is required. The existential gap between the rich Western world and the developing world is a multidimensional chasm.

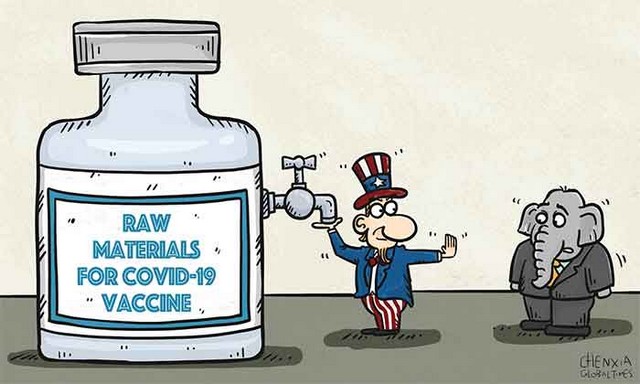

A dramatic example of the West’s indifference to the needs of the developing world will be on full display at the G7 summit. Although the US and UK, and increasingly Western Europe, have vaccinated a majority of their populations against COVID-19, the UK, to take one example, has not exported a single dose of vaccine to the developing world. It has kept all its vaccines for itself, even though its existing stock far exceeds its own future needs. As each new variant spreads around the world, however, it has become patently clear to everyone that no country will be protected until every country is protected.

In a pandemic, no country is an island. The US, which has so far failed to export a single dose of vaccine, is promising to export 80 million doses of vaccines later this year. Compare this with China’s record. In addition to the 777 million vaccinations already carried out in China, it has exported more than 300 million doses of vaccines to the developing world. Over half the vaccinations in Latin America, for example, have been sourced by China. It seems all too likely that the West will fail in its moral responsibility to vaccinate the developing world until it is too late and many millions have died unnecessarily.

***

Courtesy : globaltimes.cn, Jun 08, 2021.

Martin Jacques was until recently a Senior Fellow at the Department of Politics and International Studies at Cambridge University.

10 June 2021

SOurce: countercurrents.org