By John Wight

Che Guevera died 47 years ago, but he continues to inspire millions around the world. The popularity he enjoys so many years after his death is proof that though “they” may have killed the man, “they” will never extinguish the ideas for which he died.

On 9 October 1967, Ernesto “Che” Guevara was executed by a Bolivian army officer at the end of his ill-fated attempt to foment revolution throughout Latin America. He was executed at the behest of the CIA, who hoped his death would deal a shattering blow to the influence of the Cuban Revolution in a part of the world traditionally viewed as America’s backyard; its role to provide the cheap labor, raw materials, and markets required to maintain the huge profits of US corporations.

But the CIA were wrong, just as successive US administrations have been wrong, in thinking that the ideas for which Che Guevara fought and died could ever be ended with a bullet. On the contrary, over four decades on from his death the Cuban Revolution continues as a beacon of inspiration and hope to the poor of the undeveloped world.

That a tiny island nation with a population of just over 11 million people, located 90 miles off the coast of Florida, should have the temerity to assert its right to political and economic independence from the United States and survive for so long is nothing short of immense. Indeed, many believe that not only have the ideas for which Che Guevara gave his life survived, they have never been more potent, illustrated by the left turn taken throughout the region in recent years. It is a political turn responsible for transforming a part of the world traditionally associated with military juntas, right wing autocracies, and US puppet regimes into the very opposite.

Today Latin America is a part of the world where democracy has taken root, where the tenets of the Washington neoliberal consensus have been rejected in favor of social and economic justice as the objective of government.

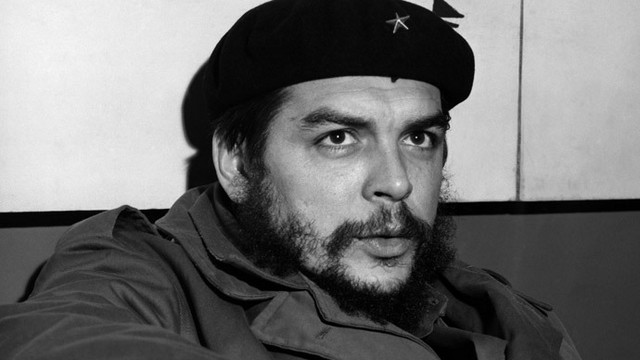

Undeniably, Che’s legend has not only continued unabated since his death it has grown. In every town and every city, from Los Angeles to London, Beirut to Bethlehem, from Nairobi to New Delhi, the iconic image of him carrying that expression of burning defiance, captured by Alberto Korda in 1960, is as ubiquitous as it is powerful, found on everything from T-shirts to coffee mugs, rugs, posters and a myriad other items. For many it represents something transcendent in the human experience, an idea that stands in opposition to the values of individualism and materialism which are drummed into us every minute of every day in the West.

A read through Che’s writings brings home the fierce determination of a man who burned with anger at the injustice, oppression and exploitation suffered by the world’s poor. In his address to the United Nations General Assembly in1964, he said:

“All free men of the world must be prepared to avenge the crime of the Congo. Perhaps many of those soldiers, who were turned into sub-humans by imperialist machinery, believe in good faith that they are defending the rights of a superior race. In this assembly, however, those peoples whose skins are darkened by a different sun, colored by different pigments, constitute the majority. And they fully and clearly understand that the difference between men does not lie in the color of their skin, but in the forms of ownership of the means of production, in the relations of production.”

Not satisfied with merely delivering such a powerful affirmation of solidarity with the poor and oppressed of another land, Che embarked for the Congo in an attempt to give meaning to them, in the process abandoning the relative comfort and status earned him by the success of the Cuban Revolution to risk his life in a mission to spread the revolution throughout the developing world.

In a later speech to the Afro-Asian Conference in February 1965, he offered this admonition:

“There are no borders in this struggle to the death. We cannot be indifferent to what happens anywhere in the world, because a victory by any country over imperialism is our victory, just as any country’s defeat is a defeat for all of us.”

For Che Guevara the struggle against imperialism and exploitation could only be won gun in hand, utilizing in his view the same kind of violence used without compunction by the oppressor. Not for him non-violence and peaceful protest. His experience, his observation of the poverty and truncated lives suffered by millions throughout Latin America and Africa instilled in him a rage and a desire to visit retribution on the system he considered responsible.

In this he was very much a product of his time, when people of the developing world were locked out of the democratic process in parts of the world where right-wing dictatorships made recourse to violence inevitable.

Despite the myriad articles, analysis, and commentary produced on Che Guevara and his life, much of it hostile and withering, one incident sums up more than any article ever could the enduring force of the Cuban Revolution whose ideas he died trying to spread.

In 2006 Mario Teran, an old man living in Bolivia, was treated by Cuban doctors volunteering their services free of charge to Bolivia’s poor, just as they have and do to the poor in every corner of the developing world in medical missions that have transformed the lives of millions. They performed an operation to remove cataracts from Mario’s eyes, which succeeded in restoring his sight.

Mario Teran is not just any old man, however. He is the Bolivian army officer who executed Ernesto “Che” Guevara in 1967.

John Wight is a writer and commentator specializing in geopolitics, UK domestic politics, culture and sport.

9 October 2014