By Richard Falk

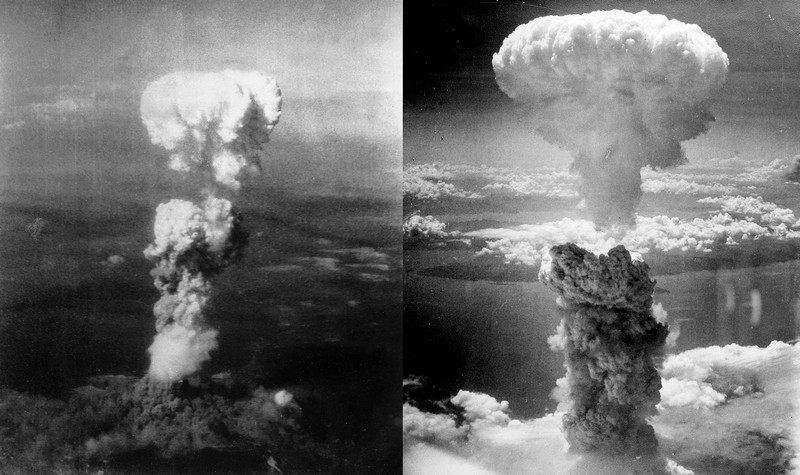

Peace activists around the world often choose August 8th each year to grieve anew the human suffering and devastation caused by dropping atomic bombs on the undefended Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Among other things it was ‘a geopolitical crime’ of ultimate terror, with no combat justification, and intended mainly as a warning to Soviet leaders not to defy the West in the peace diplomacy at the end of World War II.

August 8th falls between the utter destruction of these two cities. It is a day that can never be forgotten or redeemed, although ever since the explosions in 1945 the solemnity of these occasions has been overshadowed outside of Japan by widespread fears that a nuclear war might occur at some point and a quiet rage that the nuclear weapons states have stubbornly refused to take steps to fulfill pledges to seek a reliable path to nuclear disarmament in good faith.

This moral and political pledge became legally obligatory in Article VI of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (1970), and affirmed unanimously in an Advisory Opinion of the International Court of Justice in 1996. It has become clear that for the security establishments of the ‘NATO Three’ this disarmament commitment was never more than ‘a useful fiction’ that conveyed the sense that the non-nuclear states were being given something valuable and commensurate to their willingness to give up their conditional option to underpin national security by acquiring nuclear weapons (as Russia and China, as well as Israel, India, Pakistan, and North Korea have done over the decades). It is formally conditional by virtue of Article 10 that gives Parties to the NPT a right of withdrawal if “extraordinary events..have jeopardized the supreme interests of its country.”

Last week at the NPT Review Conference, postponed since 2020 because of COVID, at UN Headquarters in New York City, two significant contradictory developments dominated the scene. It was the first such meeting of NPT Parties since the Treaty of Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) came into force in early 2021. This treaty, a project of governments from the Global South in active coalition with Global Civil Society has drawn a bright line between the majority views of the peoples of the world and the security elites of these nine nuclear weapons states. Indeed, the NATO Three (U.S., France, UK) had the temerity to issue a joint statement stating their opposition to the approach taken by the so-called Ban Treaty (TPNW) and defiantly declared their unlawful intention to continue to rely on nuclear weapons to meet their security needs broadly specified to include geopolitical deterrence, that is, not the defense of homelands but strategic concerns that could arise potentially anywhere on the planet. At present, illustrated by the U.S. posture in response to the Ukraine War and the future of Taiwan. This impasse between the nuclear haves and have-nots amounts to an existential confirmation of ‘nuclear apartheid’ as the underpinning of global security unless and until the advocates TPNW muster enough strength and will to mount a real challenge to such a hegemonic and menacing structure of power and authority.

The second notable development at the NPT Review Conference lent a sense of immediacy and urgency to what had become 77 years after Hiroshima a somewhat abstract concern is the Ukraine War, and its geopolitical spillover effect of heightening the perceived risks of the use of nuclear weaponry and even the danger of nuclear war. The U.S. has decided it is worth challenging Russia’s attack on Ukraine sufficiently to demonstrate its claim that since the end of the Cold War the world has political space for one extraterritorial state, which is the sole supplier of global governance when it comes to the security agenda. Among other things, unipolarity means that Cold War Era mutual respect for near abroad spheres of influence no longer sustains geopolitical coexistence. The U.S. has tacitly proclaimed a Monroe Doctrine for the world, and is prepared to accept the economic and strategic burdens of doing so, maintaining hundreds of foreign military bases and navies in every ocean.

NATO’s insistence on making Russia pay for its invasion by being again reduced to the normalcies of territorial sovereignty is intended as a master lesson in the geopolitics of the post-Cold War world. It also an occasion to send China, currently the more feared adversary, a message written with the blood of Ukrainian lives, that it better not forcibly seek to regain control over Taiwan or it will be devastated in an even more punitive manner, including thinly veiled threats and possible uses of nuclear weapons. Pentagon war games some months ago ominously showed that China would prevail in any military encounter in the South China Seas unless the U.S. was prepared to cross the nuclear threshold, affirming the renewed strategic relevance of nuclear weaponry and gathering evidence helpful in gaining even larger military appropriations from Congress.

American diplomacy has aggravated an already inflammatory context by some inexplicably provocative behavior that seems designed to produce a military confrontation. First, a gratuitous undertaking by Biden to provide whatever by way of military involvement is deemed necessary to protect Taiwan against an attack by China. And secondly, a reckless August visit to Taiwan by Nancy Pelosi at a time of high tensions in violation of the spirit of the Shanghai Communique that was issued by China and the U.S. in 1972, and has kept a reasonably stable status quo ever since between the two geopolitical actors, relying on what Henry Kissinger called ‘strategic ambiguity.’ Either these Biden/Pelosi ploys are yet another expression of American amateurism when it comes to foreign policy or are deliberate efforts to provoke Xi Jinping to take action. This supposedly fearful autocrat is already being accused in China of being weak, backing down on the key policy goal of achieving the reunification of China and Taiwan. Whether incompetence or malice is worse is a matter of taste. Both are unacceptably dangerous when it comes to nuclear dangers.

In effect, remembering Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 2022 is overshadowed by this dual reality of ongoing ‘geopolitical wars.’ It is also a reminder that nuclear war was narrowly averted in the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 by what Martin Sherwin, an authoritative interpreter of nuclear risk called, ‘dumb luck.’ [Gambling with Armageddon (2020). Also relevant: Daniel Ellsberg, The Doomsday Machine (2017)]. It may also be the moment when a nascent peace movement in the Global North wakes up and pushes hard for adoption of the TPNW approach.

I was recently shocked by realizing that the 1945 signing of the London Agreement by the U.S., Soviet Union, France, and the UK agreeing to establishing a tribunal in Nuremberg charged with the post-war prosecution of major Nazi war criminals also occurred on August 8th of the same year. A parallel tribunal in Tokyo was established for Japanese war crimes some months later. It has been often observed, especially in recent years, that these initiatives were so one-sided as to stretch our meaning of criminal law, the essence of which is to treat equals equally. Inequality pervaded the work of these tribunals, although the criminality of the indicted Germans and Japanese was well-documented. What was most controversial was the failure to inquire into the violations of international criminal law by both sides, which is why these tribunals, however noble their work, were derided as glaring instances of ‘victors’ justice.’

My interest in this connection between Hiroshima and the London Agreement is somewhat different. I am appalled by the insensitivity of signing this agreement establishing the Nuremberg Tribunal on the very days when the atomic bombings were actually taking place, arguably the worst crime of World War II at least on a par with the Holocaust. It is more than insensitivity, it is moral hubris, which prepares a political actor, whether state or empire, for tragedy. It leads directly to such features of world order as a geopolitical right of exception at the UN by way of the veto and impunity with respect to accountability procedures. In effect, the UN is designed quite literally to give assurances that the most dangerous states, as of 1945, are jurisprudentially incapable of doing any legal wrong, at least within the UN System, and such later affiliated institutions as the International Criminal Court. What is this slightly disguised feature of legality and legitimacy conveying to a curious observer? That law and accountability are relevant for propaganda and punishment against adversaries, and that the wrongs of victors in major wars are beyond scrutiny but those of the vanquished and weak are to be judged in what amounts to ‘show trials’ because of this core failure to treat equals equally.

There is yet something else to reflect upon. If August 8th had been a different day that of infamy because an English or American city had been targeted by a German atomic bomb and yet Germany still lost the war, the act and the weapon would have been criminalized at Nuremberg and by subsequent international action. We might not be still living with this weaponry if the perpetrators of those dreadful events of August 6th and 9th had been the losers in World War II, which makes the aptly celebrated defeat of fascism on balance a somewhat questionable long-term victory for humanity.

In summation, there is a lot to think about on August 8th this year if we allow ourselves to grasp this repressed relationship between Hiroshima and Nuremberg in addition to heightened geopolitical tensions.

Richard Falk is a member of the TRANSCEND Network, Albert G. Milbank Professor Emeritus of International Law at Princeton University, Chair of Global Law, Faculty of Law, at Queen Mary University London, Research Associate the Orfalea Center of Global Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and Fellow of the Tellus Institute.

8 August 2022

Source: www.transcend.org