By Richard Falk

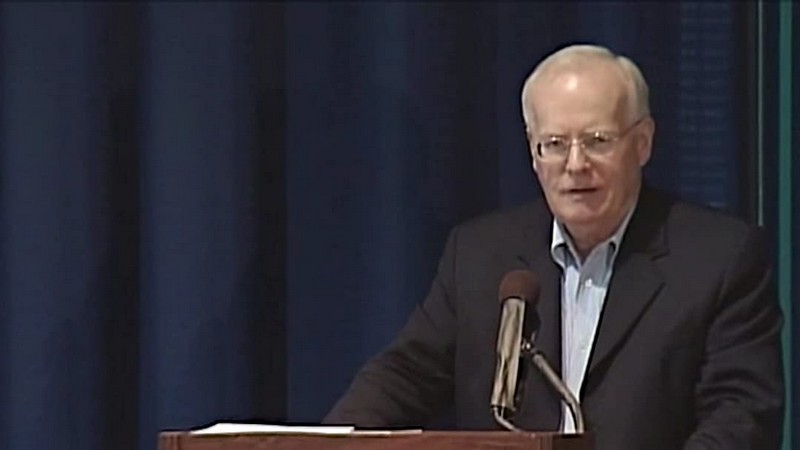

I found it sad that when David Ray Griffin died on November 2022 so little public notice was taken to report on the death of one of the most important thinkers of our time who illuminated our understanding of many crucial scholarly and academic concerns. He did so in a consistently independent and progressive manner, fully using the work of others, whether ally or adversary.

Late in life Griffin achieved fame; for some, shameful notoriety, for others as the leading exponent of an alternative narrative of what really happened on 9/11 when the key symbolic sites of US wealth and power, the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, were attacked by terrorists in 2001, resulting in the death of over 3,000 persons. To those who knew him, whether or not persuaded by his dissenting views of 9/11, there was never a loss of respect for Griffin, the probing thinker and scholar who fearlessly followed the evidence wherever it led, and whose scholarly effort was directly linked to his sense of an US intoxicated by its power imperiling itself and the world.

Griffin’s friendship and exemplary role as a public intellectual was influential and inspirational for me and many others in several realms of thought long before he became obsessed with his strong sense of duty to expose the realities of the 9/11 controversy. His earlier work had focused on a philosophical and social rethinking of the nature of religion, with a full awareness of its economic, political, civilizational, and ecological implications under conditions of modernity. It is impossible to summarize his wide-ranging interests and scholarly achievements.

Yet one feature of almost all of his voluminous writing is unusual and stands out: Griffin’s willingness to go beyond the boundaries of what was deemed by conventional opinion to be ‘responsible thought’ or ‘acceptable dissent’ as interpreted by the self-censoring filters relied upon by the most influential media platforms that made Griffin’s death a public happening that never happened. I have come to believe that it was not mainly because his views aligned with the main currents of progressive thought in the United States and abroad. Something more and different was at stake that is worth reflecting upon as a result of his public persona being linked so closely to views on 9/11 that governing elites not only wanted to be discredited but forgotten.

Like Noam Chomsky, or Jean-Paul Sartre before him, Griffin had distinguished himself by way of breakthrough scholarship long prior to venturing onto the precarious terrain of controversial politics. Yet Chomsky, eminent as a linguist before he ventured into public space with devastating critiques of the U.S. role in the world, will be recognized and even celebrated whether dead or alive as a progressive public intellectual almost everywhere in the world, raising the elusive question as to what are the elusive differences among notable public intellectuals.

In my view there are certain ‘no-go’ zones that Chomsky and Sartre more or less respected, not from prudence, but due to their beliefs and interests. In contrast, Griffin continuously breached such limits during his long productive scholarly life, even in his early philosophical and theological works that took seriously the truth claims of parapsychology and reports confirming life after death, anathemas to those who believed that modern science with its mechanistic views of causation were decisive criteria of the real.

Griffin’s early creativity centered on stripping religion of supranaturalism, while enlarging our understanding of more expansive views of scientifically verified reality. He proceeded by affirming the continuous relevance in the modern world of the stress on the experientially validated philosophical assessments associated with the philosophical work of Alfred North Whitehead and Charles Hartshorne. If Griffin had stopped here, his contributions would be appreciated by devoted followers in a few relatively esoteric academic circles, and there would be little reason to be puzzled as to why his unconventional work and life did not receive wider public recognition. Actually, a respected obit writer might have been impressed by Griffin’s work and depicted his life as centering on a maverick’s challenge to the dogmas of truth, currently strictly adhered to by the scientific community.

Chomsky and Sartre were certainly controversial and denounced by right-wing critics, but their stature as world class intellectuals fully entitled to comment on global issues was never called into serious question. Some critics insisted that their views were expressions of radical thought and neither Chomsky nor Sartre had the benefit of specialized training in international affairs, but attacks on their opinions were seen as part of the normal give and take encountered in any liberal democratic society, and especially in Chomsky’s case were largely confined to the tightly knit professional class of foreign policy experts and their bureaucratic counterpart.

True, Chomsky’s sharp criticisms of Israel and Zionism are second only to 9/11 in the pushback they receive, but Chomsky has moved on to emphasize broader issues of policy, that indict the judgment of elites, but do not question their behavior and integrity in the Griffin manner. These considerations foreground the question as to why Griffin’s later work on 9/11 set off a different set of alarms that produced this ‘conspiracy of silence’ with respect to his scholarly achievements, which were easily sufficient to have earned Griffin sufficient eminence to make his passing a public event worthy of notice and commentary.

After much puzzlement, I have come to explain this neglect of such an outstanding scholar as an indirect consequence of Griffin daring to challenge the official version of the 9/11 attacks of 2001 on the World Trade Center and Pentagon. Not only did he mount this challenge by publishing a book provocatively entitled The New Pearl Harbor: Disturbing Questions about the Bush Administration and 9/11 (2004), but he followed this carefully crafted critique with an incredible additional eleven books that debunked every facet of the official version of these events, and gained a worldwide following for what had become a crusade to bring the truths he discovered about what happened on 9/11 to the public arena in ways that would produce a reliably objective inquiry rather than a thinly rationalized whitewashing of official culpability.

What may have been even more inflammatory than the accusation that the government and the media had orchestrated a massive coverup were Griffin’s views of the motivations and consequences involved. What was undoubtedly most incriminating from the perspective of Washington and the threats posed by Griffin to its matrix of ideological control was his well-evidenced belief that this denial of 9/11 truth was tied to an underlying foreign policy agenda that had fueled past war-making and imperial interventions, and were integral to implementing the post-Cold War neoconservative resolve to fill permanently the geopolitical vacuum created by the Soviet implosion. By doing so, the U.S. could exert control over the whole world on behalf of financially-oriented world capitalism operating under the security blanket of US militarism masked as ‘democracy promotion.’

9/11 truth tellers are generally portrayed as crazy enemies of the people animated by mental disorder, which in Griffin’s case is totally false, whose personal life possessed all the attributes of middle class normalcy, including a lively involvement with a loving family. By using their pervasive influence, the overlords of public belief succeed in painting Griffin, and others who subscribed to his deconstruction of the main rationale for the War on Terror as wing nuts the established order survived the Griffin storm.

I think it was the successful branding of the 9/11 skeptics as ‘wacky’ that proved more useful in squelching their influence than by labeling them as ‘dangerous,’ ‘subversive,’ and ‘radical’ or ‘socialist.’ It might be understood as the advent of a more advanced, more sophisticated version of McCarthyism, a discrediting ploy that George Orwell would have immediately understood. I experience a touch of this treatment when the US ambassador to the UN at the time, John Bolton, called me ‘a fruitcake’ in the course of a rant opposing my appointment in 2008 as Special Rapporteur for Occupied Palestine. He called my appointment as illustrative of all that was wrong with the UN.

Griffin found his audiences around the world through well attended lectures, foreign media outlets, and most of all through his defiant books on why it was vital to get the true story of 9/11 as widely disseminated as possible. He fully earned his international celebrity by linking the exposure of the 9/11 events to the before and after stories of US foreign policy in a series of outstanding books: Bush and Cheney: How They Ruined the United States and the World (2015); The American Trajectory: Divine or Demonic (2018). Both of these books connect the grandiosity of the past US claims of Manifest Destiny and ‘exceptionalism’ to the neoconservative determination to make the entire world subject to U.S. hegemony.

Griffin’s passion and talent were saved for his dying days in a hospice when he was nearly paralyzed by pain but determined to make one last attempt to alert the North American people about the disastrous future that is being scripted in the manner of responding to the Ukraine War.

His book soon to be available to the public bears the graphic title America on the Brink: How U.S. Foreign Policy Led to the War in Ukraine (2023). This book is indispensable reading for all who want to understand why the current behavior of the United States is dooming the prospects of the human species for a peaceful and ecologically stable future.

Richard Falk is a member of the TRANSCEND Network, Albert G. Milbank Professor Emeritus of International Law at Princeton University, Chair of Global Law, Faculty of Law, at Queen Mary University London, Research Associate the Orfalea Center of Global Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and Fellow of the Tellus Institute.

27 February 2023

Source: www.transcend.org