By Harsh Thakor

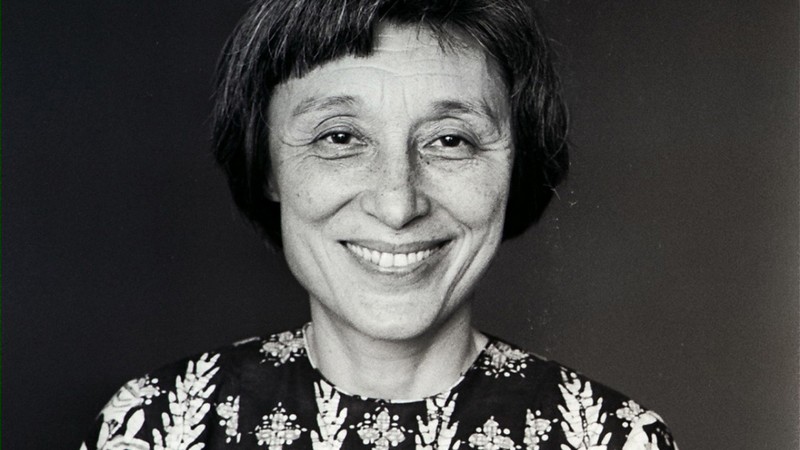

Last November we commemorated the 10th anniversary of the death of Han Suyin who left us on November 2nd, in 2012. Apart from the gratuitous obituaries in official newspapers her death was received with scant attention: passing away in obscurity, like so many revolutionary women. On her birth centenary, no noticeable commemoration meeting was staged.

Han Suyin carves a permanent niche amongst the most creative revolutionary writers from China and the world .The trademark in her writing was the simplistic style and natural flow, that projected the essence of the Chinese Revolution and China after 1949.Han could touch the core of a readers soul in conveying the extensive strides made in China .Without jargonised language or rhetoric she articulately illustrated how China after 1949 surpassed every other the world country in heath, literacy, industrial and agricultural production and democratic power of the workers and peasants.

Han Suyin’s writings described how in the Chinese Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, revolutionary democracy touched heights unscaled and gave credibility to the mass movements. In the very thick of the skin she rebuked the Western media for wrongly cast in a negative picture of China. Han gave extensive coverage of the land reform movements, creation of people’s communes, and significance of Big Character posters in the Cultural Revolution, innovative experiments in education and production, workers and peasants running their revolutionary Commitees.etc.

Her works are significant today when the Western Media and capitalist countries are leaving no stone unturned in heaping lies to discredit Marxism and distorting past history of USSR an China .They work overtime in propaganda that horrific terror was the feature of China from 1956-78 ,projecting Mao Tse Tung as a dictator.

It is my firm wish that Han Suyin’s best book are re-printed to bring to light the truth about the Chinese Revolution and Socialism when the world is one verge of it’s most grave economic crisis with globalisation engulfing every corner of the globe like a Tsunami. Her great literary style could well be emulated by progressive writers today.

At one point Han Suyin was a mascot for the Chinese Revolution. Born Elizabeth Rosalie Chou, a “eurasian” woman who came of age in China on the eve of the revolution led by Mao, Han would eventually become one of the Revolution’s literary torchbearer’s of the western world. She was a medical doctor and a novelist who, after she was gradually politically groomed by the revolution, would write social biographies of Mao Zedong and the Chinese Revolution––defending its imperative value from its beginning to the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, to the English-speaking world. And though, at the end of the 1970s, like so many communists she made the mistake of harbouring faith that the China under Deng Xiaoping would continue the revolution––that China was not going down a capitalist road––she would soon become disillusioned by China’s path to state capitalism and retire, living in near anonymity, in exile in Europe. In the mid-1990s she wrote a biography about Chou En lai and in this biography, upholding his great contribution as a Marxist.

Early Life

Han Suyin was born in Xinyang in the north-central province of Henan. Her father, who came from a landowning clan in Sichuan province, met his wife while studying abroad and took her home to semi-feudal China.

As a child in Beijing, she had fond memories of travelling to school by rickshaw and witnessing the gruesome sight of bodies of those who had died of starvation From the age of 12, she decided to become a doctor against the wishes of her mother who urged her to marry a foreigner – preferably an American because “all Americans are wealthy”.

After leaving school she paid for her fees at Yenching University in Beijing by learning to type. A Belgian businessman became her father substitute and arranged a scholarship for her to continue her medical studies in Brussels. In 1938 she returned to China to work in a French hospital in Yunnan, but was diverted on the way, meeting a handsome young officer, Tang Pao-huang (Pao), who moulded her in the Nationalist version of patriotism.

They were married that year in Wuhan, just before it was left to the mercy to the Japanese, and fled on the same boat as Chiang Kai-shek, head of the Nationalist government. They travelled west to Chongqing, the Nationalist wartime retreat, where she discovered her father’s relatives. There, she acquired her writing skill.

A missionary doctor, Marian Manly, encouraged her to sum up he story of her journey with Pao, refined the text and suggested avoiding subjects such as prostitution which might cause “misunderstanding”. The intention was to attract American readers to the Chinese cause. Bertrand Russell said that Destination Chungking (1942) – published under the pen name Han Suyin, which she kept – told him more about China in an hour than he had learned there in a year.

In 1942, when Pao was posted to London as military attache, she followed him with her adopted daughter and resumed her medical studies two years later. Through her publisher Jonathan Cape, she joined the circle of progressive Asia-minded intellectuals around Kingsley Martin, Dorothy Woodman, Margery Fry and JB Priestley. But medicine remained her goal.

Pao was posted to Washington and later to the Manchurian front where he died, fighting the communists, in 1947. Han Suyin remained in London to take her finals and then moved to Hong Kong. It was there that she met and had a passionate affair with the Times correspondent Ian Morrison. Their relationship laid the ground for ‘Many-Splendoured Thing’, which became a bestseller.

Five Volume Memoir

More important than her novels and historical biographies, however, was her five volume memoir that recounted her political evolution or crystallisation within China’s unfolding revolution. This was simply soul searching, tracing the inner or spiritual transformation of a Marxist revolutionary. A series of books where the personal was political aspects were completely mingled , these memoirs not only cashed on her subjective experience to project t and justify the revolution led by Mao right along till the end of the Cultural Revolution, but also manifested protracted literary self-criticism. They traced and illustrated her journey to communism where the older Han Suyin would critique the young and petty-bourgeois Elizabeth Chou while, at the same time, reflecting the shadow of world historical events over her tiny and limited experience.

Although these memoirs were, by the publication of the third instalment (Birdless Summer), described as “a masterpiece in progress” by The Observer, by the 1990s they were largely out of print. And by the 21st Century publishers, in a resurgence of anti-communist fever and the so-called capitalist “end of history”, would hardly give consideration in touching a literary memoir that defended Mao and the Chinese Revolution––instead these publishers were flooding book stands with reactionary memoirs such as Jung Chang’s Wild Swans. Han Suyin’s memoir counter attack to this backwards “wound literature” was considered anathema; no publisher was interested in a series of books, regardless of their literary value, where the author would place the Cultural Revolution in positive light.

Despite the fact that in 1968 The Daily Telegraph would claim that Han’s multi-volume memoirs would be “re-read two generations hence as one of the key documents of the twentieth century” these books are largely obliterated from public memory. Now the Jung Changs of the world have replaced the Han Suyins and working overtime to tarnish the achievements of Mao Tse Tung and the Chinese Revolution that confirm everything westerners wish to project revolutionary China s a ‘horror.’

Han should be resurrected by radical history because, far ahead of her time, her memoirs upheld the world historical revolution in China under Mao.

False Projection of Han Suyin

Regretfully she is remembered for the 1955 movie adaptation of her novel A Many Splendored Thing that also inspired a pop song and subsequent cliché. Still when people narrate that “love is a many splendored thing” one questions whether they had any genuine insight into Han Suyin or what she stood for. She battled for much more than a terrible movie adaptation of a novel she wrote when she was young, let alone its even more terrible pop song and trite saying.

Unfortunately, due to the fact that the majority of her books are out of print, Han will mainly be remembered for A Many Splendored Thing––that semi-autobiographical novel that was written before she was a communist. Even worse, she will probably be remembered for the movie adaptation where a white woman wearing eye make-up played her fictionalized self (since non-white women were not allowed to act as main characters in Hollywood at the time) and a complex novel about interracial love affairs in racial contexts was turned into another Hollywood romance. However those of us who are Marxists or revolutionary democrats need to remember Han as a torchbearer for a world historical revolution––someone who invested every ounce of her energy in projecting the Chinese Revolution in glowing light to her bourgeois readers in the west.

Biography of Mao

Indeed, her second historical biography on Mao, Wind in the Tower, has an appraisal of of Mao––which is redeeming in today’s anti-communist and anti-Marxist climate. Han Suyin clearly took a side––, in the moment of revolutionary upheaval, as a conscious catalyst of revolutionary ideology. In respect of her more personal and critical memoirs where she discusses being attacked by Red Guards at certain points for her political failures, It s poignant that she would create books upholding both Mao and the GPCR. Regrettably all of these books are now out-of-print and Han Suyin is dead.

Incredibly detailed and extensively cited, Suyin’s work traces the development of China starting from directly after the People’s Liberation War in ’49 up until ’75, when the book was written. The book has too strong of a tendency to shift the blame for the excesses of the Cultural Revolution onto Lin Biao- being a sharp critique of his anarchism, along with the anarchist tendencies within the party and the youth movements as I thought both were mostly valid. The coverage of the treatment of USSR-PRC relations was fascinating and informative.

Most comprehensively Han Suyin sum s up the positive political role of the Cultural Revolution.

A possible weakness here is in making no comprehensive analysis of the 2 line struggle in the final stages o the Cultural Revolution after Lin Biao perishing, with no evaluation of the Gang of Four.

Morning Deluge

In The Morning Deluge Han Suyin concentrates on the condition of the people and on the task that Mao embarked himself upon, to liberate them from the hunger, disease and oppression which made many observers 50 years ago (and less) dismiss China as a decaying backwater of futility. These two books pose a general issue of whether “the truth” about a man like Mao comes most nearly from a portrait painted with passion in broad strokes, or from an agglomerated portrait of small lines deriving from the printed data we get from and about China. Han Suyin dips her ink boldly, retaining her novelist’s selectivity in assembling choices; which result in a moral tale with the extraordinary mixture of sentimentality toward what she likes and ferocity toward what she does not

The Morning Deluge “recounts the first 61 years of the chairman’s life, from his birth in 1893 at the tranquil village of Shaoshan to the end of the Korean War, and a second volume is promised to take the story on from 1954. Han Suyin brings to life the studious nature of young Mao—he wrote more than one million words of notes and critiques during his five years of study in Changsha—and the boldness of his mind; he accepted only what he himself found to be true and then held to it unflinchingly.. She claims Mao had a “considerable following” among Changsha’s factory workers before 1919, and says a reproduction of the famous painting of him going in flowing robe with noble men in Hanyuan was hung by mistake in the Vatican in 1969 as a portrait of “a young Chinese missionary.” When Chou Enlai and others went off to study in France he stayed home because he felt he still had so much to learn about his own country.

She shows how Mao evolved, from his own unique combination of study and observation, the stress upon organizing peasants and the building of a broad front against imperialism which were the two points at which he was a torch bearer of Leninism even further from Marx than Lenin himself had done. Always Mao stressed integrating with the masses (“the many‐millioned” is Han Suyin’s word) more than blueprints, and the book rightly pictures Mao as regularly in conflict with old styled Marxists who wished to prematurely storm cities and slavishly ape Soviet models.

Being fresh from Moscow, these ultra‐leftists thought Mao was devoid in grasping “proletarian internationalism,” and were sceptical that there could be “Marxism in the mountains” where Mao was with incredible foresight and patience embarked on building guerrilla bases. Han Suyin, as a half Chinese, is understandably moved by the towering achievements of Mao, and in the chapters on the Long March and the Yenan years which followed she uses interviews conducted in China to unfold a readable drama of the new defining day in which the Chinese people finally “stood up” and re-wrote world history on equal terms.

Survivors told her how Long Marchers roped themselves together (“sleep flying”) to avoid sleep and collapse; how one marcher was perplexed when he came upon the Mao minority in Kwangsi: “I trotted up to a man I saw, but he did not understand me; I tried every word: Red Army, Jiuchin Soviet, Communist party: I called him old cousin in three dialects. He shook his head. Then thought: ‘That’s it, we’re out of China, and we’ve arrived in a foreign country where they can’t even speak Chinese.’”

The book in an organised manner touches on the moral balance against the years of anti‐Peking propaganda fed to the American general reader, and it casts a fresh perspective across certain issues: The success or failure of a united front should not be judged, it is pointed out, by whether the relations between the parties remain good, for that is not its objective; Mao’s clashes with his father were not just a private or Freudian a matter but part of a social phenomena of revolutionary times; Mao’s military and physical training interests likewise .

‘China in the Year 2001’ and ‘Asia Today’.

Two other outstanding books of Han Suyin are ‘China in the year 2001’ and ‘Asia Today.’ In ‘China in theYear 2001’ in classical manner she illustrates the essence of the ‘Great Leap Forward’, ‘The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution ‘,’Politics in Command,’,’The Atomic Bomb’ ‘Designing anew heaven nad Earth’ etc. She delves into how China attempted to create a fundamentally new Socialist man.In ‘Designing aNew heaven and earth’ she delves into the economic shphere and contrasts the production methods to that of USSR placing emphasis on agriculture .In section on the Cultural Revolution she illustratively describes the very relevance of Mao Tse Tung Thought and how in the practical sense it was dissected and penetrated in every sphere to revolutionise society .

Most poignant parts of this book were the manner during the Cultural revolution China combined functions of a peasants ,worker an soldier,the democratic initaive of the communes,thetarnsformation of agriculture at the grassroots,and the democratic methods of introducing political ideology and vivdly illustrated how the Peoples Liberation arm represnted the very soul of the workers and peasants.

In ‘Asia Today’ she portrayed why China merited the tag of a genuine revolutionary democracy .In Chapter on ‘War and Peace’ she portrayed how china’s foreign policy was fairer thanany other nation.In chapter on Cultural Revolution’She made a subtle contrast with the approach in the Soviet Union when Stalin placed single handed emphasis on the base,neglecting the superstructure.She elaborated ho wthe Cultural Revolution was the greatest revolutionary mass movemnt and firstsone of it’s kind.Vividly she illustrated how the Peoples Liberation army repreesnted the very soul of the workers and peasnts.In a simplistic manner she sumarised the reviosnist pat of Khruschev after 1956 in USSSR.Articultealy she illustrated how great strides were accomplished,unpreecdented before.

Han supporting Deng Xiapoing

Sadly after 1978 Han Suyin failed to diagnose China’s road towards capitalism and became a strong apologist of Deng Xiaoping. Han Suyin’s post-1976 endorsement of Deng Xiaopong, including her involvement in a hagiographic documentary of Deng in the 1990’s (even going as far as to say Jiang Qing was the one opposed to Deng, rather than Mao and that Deng was a great man etc); opposition to the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 (which she called, “poor young people who were misled” and explained the CPC’s dictatorship as, ““You have to have a dictatorship. How can you run a country with 22 percent of the world’s population without a strong hand?”); and even putting down Mao in comparison to Deng.I am not able to diagnose what transformed her thinking, to champion the line of the capitalist roaders.

Harsh Thakor is freelance journalist who has done extensive research on Liberation movements and Communism.

18 March 2023

Source: countercurrents.org