By Rami G. Khouri

BEIRUT — The dispute between Saudi Arabia/United Arab Emirates and Qatar has added major new developments and regional dynamics to existing dramatic situations across the Middle East — especially in Yemen, Syria, Iraq, Libya, and Palestine. Diving deep into any of these situations inevitably leads one to some of the others, confirming again and again the interconnections between the many actors and issues that have generated so much violence and uncertainty in the Arab region.

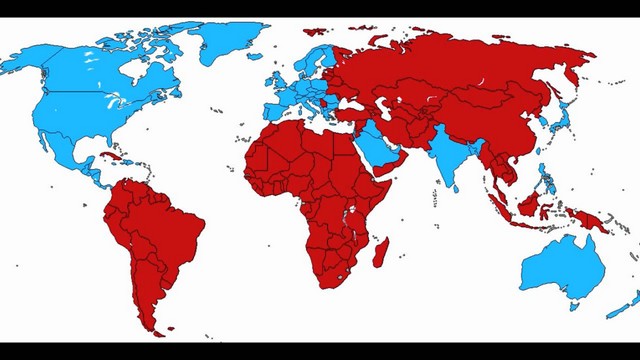

So it might be useful to step back from examining any one conflict and instead simply try to identify larger historical and political patterns that help us understand the players and the issues at stake. The latest dispute in particular, focused on Qatar and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), has generated a flurry of speculation about new alliances coming into being. The most popular one is a possible alliance between Qatar, Iran, Turkey, and Russia to face off against the Saudi-Emirati-led group of half a dozen countries that have lined up against Qatar. While nothing can be ruled out in the modern Middle East, this kind of instant alliance-formation seems more reflective of a Western tradition of toying with Arab lands and peoples like a handful of putty, rather than any serious analysis of realistic expectations.

We can, however, survey the region and identify notable new political dynamics and actors in the Arab World’s past several hundred years of colonial entanglements, state formation, and foreign military interventions. However the Qatar-GCC, Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Libya situations are resolved, I suggest that we can see in them the beginning of a new era that has taken a quarter century to come into focus — since the end of the Cold War around 1990.

I see this as a new era because of several novel developments. One is the phenomenon of two very small and very young Arab states — Qatar and UAE — playing much bigger regional and global roles militarily and politically than their geography and demography would normally suggest. Another is the spectacle of several Arab energy-producing wealthy states like Saudi Arabia and the UAE ganging up against a third, Qatar, using siege tactics that cause havoc regionally and seek to bludgeon it into submission to their will — despite their having spent several decades trying to create a GCC regional block that values stability and security above all else. A third is the direct military, strategic, political, and economic involvement of two regional non-Arab powers — Turkey and Iran — in both participating in and trying to resolve the disputes. And a fourth is the role of the two big global powers — the United States and Russia — who promote a mediated resolution to the Qatar-GCC and Syria conflicts, but often also are vexingly imprecise on their bottom lines.

Two important things about these phenomena are that they all reached maximum impact and clarity in the last six years since the 2010-11 Arab uprisings, even though their roots sprouted during the post-Cold War years; and, they include within them a relatively clear scorecard of actors, identities, and ideologies that now battle in the open to define the Arab region, whether through the policies of the existing states or large non-state actors like Hizbollah and Hamas.

Perhaps this clarifies the major forces at work that now compete for the soul, spirit, and sovereignty of the Arab region and its many smaller components. I would list the following as the players to watch in this respect: Foreign big powers (U.S., Russia, for now), regional non-Arab powers (Iran, Turkey, for now), Arabism even in its faded state, Islamism even in its subjugated state, oil-anchored materialistic patriarchy (the energy producers and their dependents, like Egypt), and remnants of former socialist-nationalist-military states in Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and other places.

These actors and a few other smaller ones now wage battle in the open to shape the identities and policies of the existing Arab countries. It is unlikely that any one or two will achieve full victory and dominate the region, as imperial powers did in history. More likely is that most of them will coexist in uneasy truces, as the region gets back to a developmental phase in a no-war context that can resume the socio-economic growth needed to respond to people’s basic needs and thus achieve lasting security and stability.

The most striking thing about this situation is that the ordinary Arab citizen is not among the powerful forces battling it out for the soul and sovereignty of the Arab region, which has been the case for centuries, unfortunately. One day, who knows when, the final battle of the modern Arab era will take place and witness the will of the citizenry struggle to achieve supremacy over the stultifying power of autocratic local elites and foreign powers that have subjugated hundreds of millions of men, women and children for hundreds of years. The Arab uprisings of 2010-11 hinted at that eventuality; but they were quickly put down by local and foreign forces of autocracy and control that have stepped out into the open more clearly this week in the Qatar-GCC crisis.

Rami G. Khouri is senior public policy fellow and professor of journalism at the American University of Beirut, and a non-resident senior fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School Middle East Initiative.

14 June 2017