By John Wight

Is the Trump administration embarked on a foreign policy of driving a strategic wedge between Russia, China, and Iran? Given the precedent set by the Nixon-Kissinger strategy of the 1970s vis-à-vis Russia and China, the question is pertinent.

Trump’s foreign policy since he assumed office can be boiled down to the simple, if not simplistic, proposition of peace with Russia and conflict with China and Iran. The problem with such a policy, of course, is that any conflict with China or Iran will make peace with Russia hard to achieve given that both are longstanding allies and partners of Moscow, and therefore would place Russia in a difficult position.

Regardless, there are those who continue to project faith in Trump based on nothing more concrete than the fact he isn’t Barack Obama or Hillary Clinton. This is political illiteracy of the most basic sort, especially in light of the maiden speech of the new president’s Ambassador to the UN, Nikki Haley, to the Security Council over the resumption of conflict in eastern Ukraine. “The United States continues to condemn and calls for an immediate end to the Russian occupation of Crimea,” Haley said. “Crimea is a part of Ukraine. Our Crimea-related sanctions will remain in place until Russia returns control over the peninsula to Ukraine.”

They are words that could have been lifted verbatim from any number of speeches delivered to the UN Security Council by Haley’s predecessor, Samantha Power. They reveal the Trump administration is intent on continuing the lie that Crimea was ripped from Ukraine against the will of the overwhelming majority of its citizens, and that the Ukrainian government in Kiev has legal authority over those who refuse to accept the legitimacy of the coup, backed by the US and its European allies, which brought it to power in 2014.

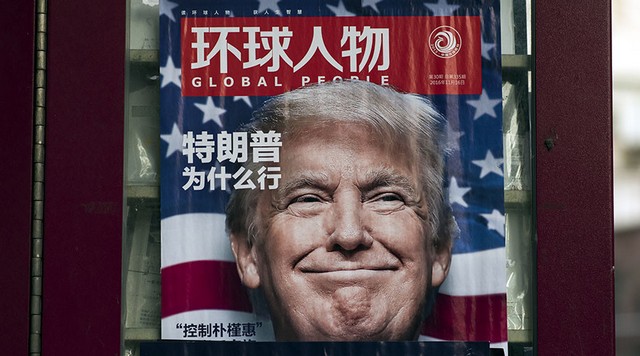

Turning to China, the school of thought which contends that Trump is merely setting out a hard bargaining position to reboot trade relations between Beijing and Washington on terms more favorable to the latter is delusional. It is a position that fails to take into account that China is currently preparing for the possibility of military conflict against the US in the near future. Understandably so given Trump’s saber rattling over the ongoing territorial dispute in the South China Sea, and understandably so given Trump’s statement that the One China Policy, under which Washington accepts Beijing’s strongly held position that Taiwan is a breakaway province of China rather than an independent state, may be up for negotiation. Predictably, the prospect has gone down like the proverbial lead balloon in the Chinese capital. East Asia, before Trump’s election, was already a region where tensions had been intensifying in recent years, reflected in a sharp increase in spending on defense by China and Japan, along with Singapore, South Korea, and Vietnam.

When it comes to Trump’s claim that China is guilty of currency manipulation, it is evident he is living in an upside down world. How has the United States been able to maintain an economic model supported by otherwise unsustainable debt and hyper-consumption if not for the manipulation of its currency? Indeed if it was not for the US dollar’s status as the world’s dominant international reserve currency, and if not for China being willing to buy so many of them, the US economy would have collapsed way before now. Yes, the US has been China’s biggest export market over the years, but the relatively low cost of Chinese imports has helped keep the cost of living down for Americans, especially during the worst years of the global recession, thus enabling them to continue the hyper level of consumption that is key to the US economy.

Rather than devaluing its currency, China has been doing precisely the opposite, offloading US Treasury Bonds over the past year to increase the value of its currency, the yuan, against the dollar. Whether Beijing’s motives in doing so are entirely economic, or if there is a strategic motive involved, given that the US economy is vulnerable in this regard, this is hard to say with certitude. But considering the ongoing territorial dispute, previously mentioned, and China’s growing concern over the build-up of US naval resources in the region, it would be naïve to discount one.

When it comes to Iran, the Trump administration is determined to join with Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in placing pressure on a country that has been a solid pole of opposition to both Israeli expansionism and US hegemony in the region over many years. Trump’s National Security Advisor, Michael Flynn, recently threatened Iran in response to a missile test that was undertaken, accusing the country of engaging in “destabilizing behavior across the Middle East.”

It is utter nonsense. The states in the region that are most guilty of “destabilizing behavior” are Israel and Saudi Arabia, both longstanding allies of Washington, whose consistent rattling of sabers toward Tehran is the real cause of rising tensions. Furthermore, Saudi Arabia’s actions in Yemen are an offense to any conception of legality or justice, yet in response, Washington continues to turn a blind eye.

Michael Flynn, it should be noted, had already been labeled an Islamophobe prior to being appointed Trump’s National Security Advisor. In a video of a speech he gave last year, the National Security Advisor described Islam as a “malignant cancer.”

His ignorance in this regard is both astounding and horrifying, especially when we consider Washington’s role in slaughtering and destroying the lives of millions of Muslims in recent years, its role in destroying Iraq, Libya, and turning the entire region into a mess. The Salafi-jihadist menace that erupted in response has killed more Muslims than members of any other religious or cultural group, and it is Muslims who have been doing the bulk of the fighting on the ground in resistance to it – specifically the Muslim-majority Iraqi Army, Syrian Army, Iranian volunteers, Hezbollah, Kurds, and so on.

President Trump’s first few weeks in office have provided enough evidence that it is far too soon to place faith in him ending a Washington foreign policy predicated on US exceptionalism.

Returning to the question posed in the opening chapter, what Russia has to consider when it comes to the foreign policy of the Trump administration at this early stage is the high probability of it being driven by the desire to weaken or indeed split the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), of which Russia and China are founding members. The Nixon-Kissinger strategy of the early 1970s resulted in the United States normalizing relations with China to capitalize on the Sino-Soviet split, thus driving a wedge between both to Washington’s strategic advantage.

Back then the strategy worked superbly from Washington’s point of view. Allowing it to do so a second time, and this time allowing the US to normalize relations with Moscow at the expense of Beijing, would constitute a historical blunder of monumental proportions from the standpoint not only of China but also Russia.

6 February 2017