By Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirovic

From the very political point of view, the 19th century in Latin America started in 1808 when the emancipation of the subordinated people against the foreign (Spanish & Portuguese) rule started (and finished in 1826) and was over with the beginning of the Great War in Europe in 1914. The struggle for independence was extremely speeded up by the French military-political subjection of the Iberian Peninsula when both Spain and Portugal lost direct connections with their overseas colonies. Such a new geopolitical situation fostered domestic Latin American patriotic nationalism which demanded political independence, administrative sovereignty, and economic self-administration instead of the subordination and exploitation by colonial motherlands with their capitals in Madrid and Lisbon.

These political, administrative, and economic requirements were met by the Portuguese royal court by accepting them and consequently leading the biggest Portuguese colony – Brazil toward the creation of political nationhood as an independent state (Kingdom in 1815, Empire in 1822, and Republic in 1889) on peaceful way but with a minimum of social change. This characteristic was common for almost all ex-Iberian colonies in Latin America (Mezo/Central- and South America): political independence did not change a social framework and relations within society from Mexico to Cape Horn.

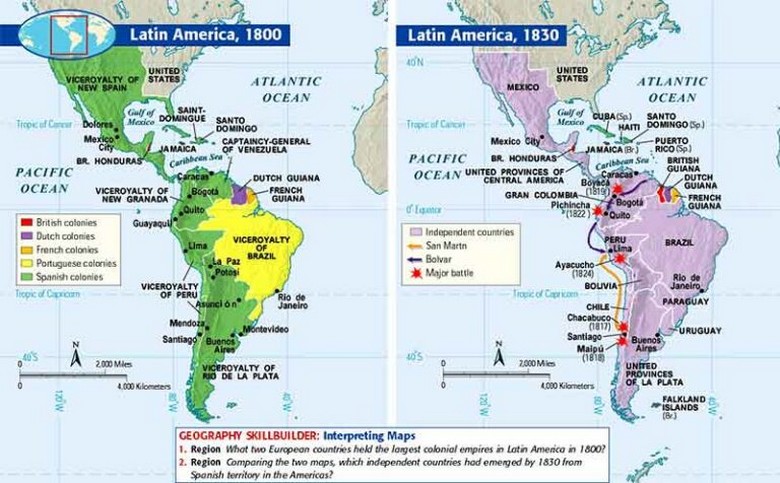

Differently to Portugal, Spain, on the other hand, adopted from the very beginning of the Latin American liberation movements the policy of military confrontation with the nationalists for the sake of eliminating all political, administrative, and economic demands of its Latin American colonies, in fact, by the brutal way. Such policy, however, directly provoked the revolutions for independence across both Central America and South America. As a result, within the South American Spanish colonies, there were two revolutionary movements for independence against the administration in Madrid: 1) The southern revolution going from Buenos Aires toward Peru via Chile and led by San Martín’s Army of Argentinians and Bernardo O’Higgins’ Chileans (Battle of Maipu in Chile in 1818) attacking Lima – the capital of Peru; and 2) The northern revolution that was more seriously harassed by the Spanish army, was headed by Venezuelans Simon Bolívar and Antonio José de Sucre (Battle of Boyacá in 1819 in New Granada/North Colombia) and back to Venezuela. Nevertheless, both movements met each other in Peru – at that time the fortress of Spanish colonial rule in America.

In Central America, the Mexican revolution of independence was of its own nature: it started as a social uprising but then became a prolonged counter-revolution, and ultimately was finished as a successful power seizure by the conservative military commander Iturbide who became enthroned as Emperor Agustín I.

The independence wars in Latin America (1808−1826) as a result brought independence for ex-colonies but this independence was essentially only of a political nature which, in fact, only transferred political-administrative authority from the colonial power to domestic landlords with minimal social and economic change within the society which structure left as it was during colonial time. Nevertheless, the independence wars across the continent ended with great loss of both life and property. In addition, revolutionary and counter-revolutionary terror followed by insecurity resulted in a struggle between the owners of capital and the labor force that was very difficult to restore the pre-war economy.

Very soon after the wars of liberation started a violent struggle between the political center and surrounding regions, ideas of free trade and protection, agriculturalists, mine-owners, and industrialists, supporters of cheap imports vs. proponents of national production and export. For instance, the violent struggle between liberals and conservatives lasted in Colombia for more than a century. Finally, the business vacuum in Latin America left by the Spanish colonial administration was soon covered by Western (British, US, French) merchants within the general trend of cheap import and primary export. All new Latin American nations were export economies founded on the exploitation of cheap land and labor for the production of raw materials for Western industries and the global market. National industries were left underdeveloped while common economic institutions were mine, ranch, and plantation. Latin America in 1913 experienced the biggest foreign investment from the UK (more than 50% out of the total) followed by the USA, France, and Germany.

From the 1880s, massive immigration of both foreign capital and manpower occurred which fostered economic growth. For instance, in both Brazil and Argentina, the Italians were at the top of the immigration number followed by Portuguese immigrants to Brazil and Spanish to Argentina.

Unfortunately, the national economic development of Latin America soon after gaining political independence was impossible due to the old-preserved social structure of the new political unities as an impoverished population from the villages did not provide substantial support for the local industry in the cities. The essence was that the old West European (Spanish, Portuguese, French, Dutch, and British) colonial system of production and social relations founded on it remained without serious changes. In practice, it meant that two existing social strata were sharply divided: 1) Privileged minority (of exploitation) who monopolized both civil offices and the land for production followed by 2) Hardly surviving peasants and industrial workers.

Economically speaking, in the 19th century emerged a new power social-economic basement – hacienda, the great land estate (much bigger than a ranch) that was utilizing much more land compared to invested capital surviving by a cheap labor of both natures: servile and seasonal. On one hand, slavery, and the slave trade were soon abolished in all newly proclaimed independent states of Spanish Latin America (by the 1850s). However, in Portuguese-speaking Brazil, slavery, on the other hand, lasted until 1888. Nevertheless, as it was in the pre-colonial time, the Negros (African Blacks), Mulattos (White-Blacks), and Mestizos (White-Indians), were left at the bottom of the social structure.[1] In fact, all of these three socioeconomic groups became peons (In Europe of the Middle Ages – serfs) – peasants allowing a small portion of land within the territory of a hacienda in return for hard labor work on the land. After the independence wars, the new political-administrative establishment in Latin America tended to reduce as it was impossible, at least by the law, racial discrimination based on social, economic, and ideological foundations which in practice did not work properly. The new political establishment intended to integrate native Indians into the newly established nations (based on the West European colonial division) by, in fact, forcing them to participate in post-colonial economic production. In practice, such policy presumed to divide the communal lands among individual owners (agrarian reform) which in theory has to benefit the native Indians. However, it became obvious in the practice that such agrarian reform just strengthened Indian white neighbors.

As in many other similar cases, concerning Latin America, the wars of independence created local war leaders (caudillo) who introduced military-political structure above civilian institutions. However, caudillo was at the beginning just a military leader, he, as well as, soon occupied other social and political roles becoming, in fact, a national dictator, who represented economic and national interests. He, also, became a distributor of patronage (office and land) as being at the top of a patron-client structure.[2] Up to WWI, Latin America passed through a time of brutal policy of caudillismo, when, for instance, Santa Anna in Mexico, Rosas in Argentina, Páez in Venezuela, etc., have been governing their states as a private possession (extended hacienda) like the medieval rulers in Europe.

Nevertheless, the practice of caudillismo was in some cases subject to constitutional challenge. The number of presidents in many Latin American new nations was changed frequently as in the case, for example, Mexico, which had 30 presidents during the first half of the century of its independence. A Mexican president Benito Juárez was fighting the forces of privileged social strata united together with French imperialists who for a short period succeeded in installing their puppet Emperor Maximilian I, on the throne.[3] Benito Juárez by 1867 subordinated both the Roman Catholic Church and Mexican armed forces to the level of secular state. However, Mexican liberals, who provided their country with a higher level of political freedom, at the same time were not able to provide economic prosperity and higher living standards for the citizens. Within the framework of one decade, the liberals paid way for the long-time political authoritarian regime of Porfirio Díaz.[4] His presidency experienced enormous economic progress but, however, making the country dependent on foreign capital investment and left the majority of the citizens in terrible poverty. Such an economic situation provoked in 1910 Mexico’s second revolution.

In essence, within the whole territory of Latin America, economic growth directly assisted in undermining the political regimes that promoted it. There were two reasons for including Latin America into the global market around 1900: 1) A huge investment in agriculture and mines by West European countries and the USA, and 2) Massive West European emigration (primarily from Italy, Spain, and Portugal). There was a “pampas’ revolution” in Argentina which made the country a global producer of meat and grain. Some other Latin American countries, like Mexico, Brazil, and Chile, succeeded in modernizing and commercializing economic production. At the same time, they speeded the export of food and raw materials due to and via railways and docks.

However, due to unbalanced economic dependence, there were too many risks and failures. For instance, the famous silver mine (and city) of Potosí during the Spanish colonial exploitation, declined in the 19th century to be only a simple town in the Andes. There was a nitrate boom in production from 1880 to 1919 due to the Chilean territorial gains from Peru (province of Tarapaca) and Bolivia (province of Antofagasta) in the War of the Pacific from 1879 to 1883. Nonetheless, after WWI, the Chilean nitrates industry declined due to synthetic subsidies. In 1914, oil was discovered in Venezuela which in the interwar period (1918−1939) produced extremal differences between the wealthy and poor people. There were towns of Iquitos in Peru and Manaus in Brazil that for a short period promoted them into global prominence due to the rubber production.

All these economic events promoted a social-living change in society primarily having a direct impact on the speedy process of urbanization followed by the emergence of new social groups whose everyday life strictly depended on contemporary technology (concerning production) and trade (in essence in global terms). That was, in fact, a Latin American (urban) middle class that emerged not belonging either to landlords or peasants.

Regarding political developments in Latin America in the 19th century, the people of the continent have been in wars not only for their national liberation against Spanish and Portuguese colonial authorities but, as well as against each other for territorial gains. Only Brazil was the exception that fragmentation did not swiftly follow emancipation/independence, which concerning Latin America led finally to the twenty independent states (political unities). Boundary disputes have been occasionally on the agenda causing some major wars between the Latin American republics. That was, for instance, the case with the Mexican-USA War from 1846 to 1848 which resulted in the secession of Texas, which cost Mexico California and in sum 40% of the Mexican original state territory. It was the 1864−1870 Paraguayan War, in which three Atlantic-facing states (Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina) defeated and ruined Paraguay – a country in which native Indians succeeded in preserving their ethnocultural identity.[5] This war was followed by the 1879−1883 War of the Pacific when Chile, Peru, and Bolivia joined the battle for the sake of controlling the important Atacama Desert rich in nitrite deposits. Finally, in 1883, Chilean military victory over Peru and Bolivia followed by the accession of lands from both of them, made Chile to be the major Pacific power. As rich natural nitrite deposits were annexed in both wars in the north, Chile enjoyed the next five decades with a real economic boom.

Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirovic, Ex-University Professor, Research Fellow at Centre for Geostrategic Studies, Belgrade, Serbia

3 June 2024

Source: countercurrents.org