By Stephan Shaw

‘It happened, therefore it can happen again: this is the core of what I have to say.’

‘Consciences can again be seduced and obscured: even our own.’

– Primo Levi

Not This Israel, Not this Jew

For a long, long time I packed away my Jewish education and my soft spot for Jewish ethics and philosophy. It went to a dusty corner that I learned to forget. The notion of “Jewish ethics” once weighty and important, could seem quaint today, if not entirely outrageous. Jewish ethics are so plastic it seems that they now encompass and countenance genocide. It’s now obvious to all who care that Judaism has become what the theologian Martin Buber had warned of last century, a victim of the dehumanized colonization and dispossession of others. It turned long ago into nationalism and a question of sovereignty, not of God, but of land. The Atzei Chayim in the Ark of the Covenant was replaced by two hellfire missiles, and we went from sanctifying the Sabbath and thanking God for life to sanctifying our hatred and praying to God for the annihilation of the Palestinian. If there is anything positive from this moment in history in Gaza, it’s that the fig leaf cover of Israel’s viciousness is falling off.

Since I was a young boy born into a secular Jewish household, I’ve struggled in the space between professed “Jewish values” and actual Jewish politics. My grandparents came here as children, fleeing pogroms and discrimination. By the time my grandfather was forty, he was a small business owner and standing proudly on his feet. America had become a beloved home for my secular, jewish family.

I never experienced anti-semitism growing up. I wondered about that, because I was always hearing about it, told that it lurked in every corner. I was the first in my family to have a formal American, Jewish education. It’s an unusual, almost biblical story: I was essentially sold into the religious institution for my older brother’s sake. He had decided out of nowhere at the age of twelve that he wanted to be Bar Mitzvahed. The Rabbi told my parents that because he was already nearly thirteen, he couldn’t do a traditional Bar Mitzvah. However, he told my parents, if they enrolled their youngest son, he would bend the rules. And so, at the age of seven, I was enrolled in what they call in the US a Hebrew School, and my brother had his shotgun Bar Mitzvah.

In my first year, the curriculum was divided between learning to read Hebrew (not to understand it, mind you, but just to read the script so we could recite from the Torah) and “current events”. The current events class was, in retrospect, our introduction to what is called Hasbara (which can most succinctly and fairly be defined as sophistry.) We learned that Israel was an empty desert that the Jews made bloom. We learned that though it was called the land of milk and honey in the Torah, it had lain fallow until Jewish refugees brought their hearts, minds, and labor. Oddly, the lion’s share of each class was a discussion of the Israeli military, including inventories of weaponry and histories of tactical brilliance. We were taught about the Holocaust and how, as Joe Biden would have it today, there is no safety for Jews except for Israel. We learned to intone the phrase “never again” with complete conviction. All this took place in my Hebrew school in Long Island, NY, which felt for me in the 70’s a very safe place for a Jewish boy with mostly Christian friends.

I was eventually Bar Mitzvahed, but as far as I was concerned, it was the end of my being Jewish. There was little in Hebrew School that spoke to me. We were, of course, taught some of the beautiful parts of Judaism, like Tikkun Olam, the Jewish command to repair the world – but back then, in my school, Tikkun Olam boiled down to raising money to plant trees in Israel. I planted dozens. I didn’t know it then, but Israel was uprooting as many olive trees in the West Bank as we could raise money for trees somewhere else. Today, Tikkun Olam has expanded for some to include raising money to arm West Bank settlers with AK47s.

Abraham Joshual Heschel, a shining light of Jewish theology and philosophy, long bemoaned Jewish education in the United States, fearing that many Jews would fall from the faith if they were not nourished on ethics and tradition. He wrote that American Jews would do a better job than Hitler in erasing Judaism from the planet. One of the oldest Jewish commandments, he taught, was the refusal of idolatry along with the core principle that Judaism was not about place or land, but service and rejoicing in the Sabbath. My entire religious education seemed to have just two pillars: worshiping the golden calf of Israel and fearing for my safety, neither of which I wanted any part of, but as a kid it didn’t make much difference to me. I moved on.

It was only in college, when Israeli documents from the first half of the 20th century had been made public and the New Historians of Israel, like Benny Morris, Avi Shlaim and Ilan Pappe, published the truth of the founding of Israel, that I fully woke from the lull instilled in me throughout Hebrew School. The reckoning of Jewish history – from the terror of European pogroms and the Holocaust, to committing outright terror, murder and appropriation in Israel – was and is not easily absorbed. That it was so flagrantly counterintuitive helps to explain how little it penetrated into Jewish spaces. It also explains the outright shock that so many Jews feel today at the genocide case before the ICJ. As Ilan Pappe wrote years ago, liberal Zionists “find themselves confused and disoriented, representing the oppressor, the colonizer and the occupier.“ There is a mental dissonance in the contemporary situation that it seems most minds cannot process; an identity crisis created by an attachment to a mythos that no longer carries any water. It is often deflected by blaming Netanyahu for all the problems, but that is like blaming all of America’s problems on Trump.

It was in 2008, when Israel had launched another “mowing of the lawn”, the sardonic and vicious euphemism for indiscriminate use of force and deliberate murder of civilians, that I, counter-intuitively, found my way back to being a Jew. In 2008 I felt one thing acutely – I could not tolerate the worst crimes in international law going down in my name. At the time my reclamation felt perverse, like it had something in common with the way Nazism forced secular Germans to be Jewish when they had only considered themselves German previously. Primo Levi discussed how the Nazis stamped him into a Jew: ‘If it hadn’t been for the racial laws and the concentration camp, I’d probably no longer be a Jew, except for my last name … the racial laws and the concentration camp, stamped me the way you stamp a steel plate.” It was the unimaginable events of the Shoah that forced Levi to wear the insignia of Judaism. But towards the end of his life, and certainly a factor in his suicide he began to show signs of shame and disgust. “It happened, therefore it can happen again: this is the core of what I have to say.” Elsewhere, he added, “Consciences can again be seduced and obscured: even our own.” At the end of his life, he confessed, “I retain a close sentimental tie with Israel, but not with this Israel.”

Levi committed suicide months after the first intifada. It is my sense that he could not bear the crooked timber of humanity any longer – the sense that all of us are capable and complicit in genocide. His own history of victimization was not capable of silencing the victimization of others. He did not see a path forward for himself as a human or a Jew. Today, the majority of Jews are, in Heschel’s words, accomplishing what even the Nazis could not – undermining Judaism itself. My great heritage for thousands of years was ethics – “justice shall you pursue,” Deuteronomy proclaims – but since I was a child it has only been about power and land. Half of the Ten Commandments now lie shattered at the feet of innocents in Gaza. If to kill one person is to destroy a world, we have destroyed universes.

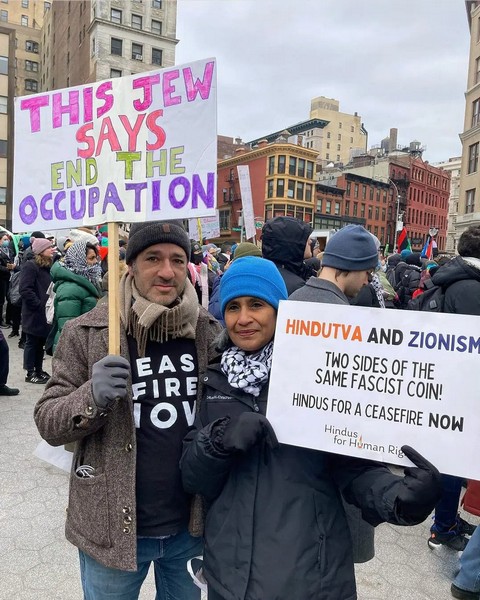

But there is a different path forward for Jews, even now. I am a Jew of conscience, not in unending victimization and war, but in truth and reconciliation. The bombing of Gaza stamped me the way one stamps a steel plate. The way Levi was stamped. In my case, it is with the revulsion and direct knowledge that it is we who are acting out the larger share of this tragedy, and that therefore we can stop it. I’ve come to believe that louder voices have for too long told all the wrong lessons of the Holocaust. I’ve come to believe that solidarity with Palestinians is the true counter-testimony to Auschwitz and the way forward for Jewish ethics. Far from being anti-semitic, the protests I’ve been going to are philo-semitic and in the deepest interest to Jews everywhere. Think what you want about the Orthodox Jewish Neturei Karta, the visual epitome of Jewishness that have been showing up with their children at all the demonstrations in the US, but they are embraced, celebrated and loved by everyone there. It is not the same as the Israeli embrace of Christian Zionism which is shortsighted and nihilistic.

At the end of his life, Levi spoke about the Jewish future. “The center of gravity is in the Diaspora,” he wrote, “I, a diasporic Jew, much more Italian than Jewish. I would prefer that the center…of Judaism remained outside Israel.” He concluded his statement by calling all Diaspora Jews to fight against the degradation of political and ethical life in Israel.

I have never felt more Jewish than when I joined Jewish Voice for Peace at Grand Central Station on October 27th, our shirts declaring “Not in my name.” To quote Heschel again, it felt as if I was praying with my feet; it felt as if I was praying for the first time. I am as certain as I am of anything that every one of my fellow Jews in handcuffs, atheists and orthodox alike, prayed that night more deeply than at any other time in their lives. Since that day, I’ve marched and been arrested with friends from every walk of life, Jewish, Buddhist, Muslim, Hindu, Punk, chanting together that there is no safety or future in occupation and murder.

I am a Jewish man and I will not be forced to condemn Hamas as a litmus test or a catechism to be recited. At this point it feels to me an act of trivialized routine or a justification for Genocide. I am against all killing but I have a particular obligation to call out the killing by Jews. There has never been a dearth of condemnation for the actions, both wretched and noble by Palestinians. There has always been a dearth of condemnations of Israel for fear of being anti-semitic. I am with Judith Butler in asking how we might release the region from violence such as this rather than simply condemning. But I know we cannot fulfill any spiritual destiny without coming to terms with the Palestinians who languish in the way that we did once, we who were slaves in Egypt – something we are reminded of every Passover. The story of Exodus, our liberation from bondage, is the core of what it means to be a Jew. But this simple truth must be acknowledged: freedom cannot exist on the backs of other people. Too many consciences have been seduced into believing there is a Jewish exception to this rule.

Uncritical support of Israel is destroying the spiritual core of Judaism itself – a dagger in the Jewish heart. Heschel wrote that “good and evil live in promiscuity but our powers of discernment have been stupefied.” He warned long ago, as the Vietnam War raged and the Jewish conscience refused to speak up for fear of angering American power, that we risked becoming value-blind. As I listen to the increasing calls for genocide in Israel and in the US, as I watch the grimmest images since the Shoah of the first televised genocide in history, I need no more evidence of this truth. Christians had to reckon with their deeds after the Holocaust. Jews need to do that now. Israel may have a right to exist, but not this Israel. It’s counter-intuitive and difficult to digest but conscience can be seduced and obscured: even our own. I promised never again. Never again is now.

Stephan Shaw is a musician and Hegel scholar, activist in Jewish Voice For Peace, a proud husband of Sunita Viswanath and father of three marvelous boys.

22 January 2024

Source: forsea.co