By Julian Borger

Twenty million Yemenis, nearly 80% of the population, are in urgent need of food, water and medical aid, in a humanitarian disaster that aid agencies say has been dramatically worsened by a naval blockade imposed by an Arab coalition with US and British backing.

Washington and London have quietly tried to persuade the Saudis, who are leading the coalition, to moderate its tactics, and in particular to ease the naval embargo, but to little effect. A small number of aid ships is being allowed to unload but the bulk of commercial shipping, on which the desperately poor country depends, are being blocked.

Despite western and UN entreaties, Riyadh has also failed to disburse any of the $274m it promised in funding for humanitarian relief. According to UN estimates due to be released next week 78% of the population is in need of emergency aid, an increase of 4 million over the past three months.

The desperate shortage of food, water and medical supplies raises urgent questions over US and UK support for the Arab coalition’s intervention in the Yemeni civil war since March. Washington provides logistical and intelligence supportthrough a joint planning cell established with the Saudi military, who are leading the campaign. London has offered to help the Saudi military effort in “every practical way short of engaging in combat”.

On western urging, Riyadh had promised to move towards “intelligence-led interdiction”, stopping and searching individual ships on which there was good reason to believe arms were being smuggled, and away from a blanket policy of blocking the majority of vessels approaching Yemeni ports. But aid agencies and shipping sources say there is little sign of any such change. UN sources say that only 15% of the pre-crisis volume of imports is getting through, and that the country depends on imports for nine-tenths of its food.

“There are less and less of the basic necessities. People are queueing all day long,” said Nuha Abdul Jabber, Oxfam’s humanitarian programme manager in the Yemeni capital, Sana’a. “The blockade means it’s impossible to bring anything into the country. There are lots of ships, with basic things like flour, that are not allowed to approach. The situation is deteriorating, hospitals are now shutting down, without diesel. People are dying of simple diseases. It is becoming almost impossible to survive.”

In April, Saudi Arabia pledged it would completely fund a $274m UN emergency humanitarian fund for Yemen, but so far none of the money has been transferred to the UN Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Riyadh is nonetheless insisting upon the right to decide which aid workers can enter Yemen.

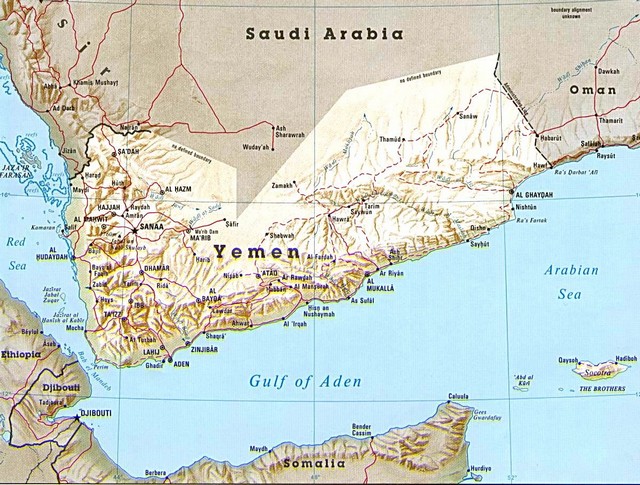

At Al Hudaydah on Yemen’s west coast, the only major port still functioning, a trickle of humanitarian food supplies is arriving on a handful of aid ships allowed through the naval blockade each week, but many more ships are being turned away or made to wait many days to be searched for weapons.

A State Department official said Washington was pressing for basic goods to be allowed through the blockade. “We continue to urge all sides, including the Saudis, to exercise restraint and avoid unnecessary violence,” the official said in an emailed statement. “We also urge all parties to allow the entry and delivery of urgently needed food, medicine, fuel and other necessary assistance through UN and international humanitarian organisation channels to address the urgent needs of civilians impacted by the crisis.”

Britain’s Royal Navy has liaison officers working with their Saudi counterparts, and they have been trying to urge a more targeted, intelligence-driven, approach to stopping a much smaller number of ships, so far with limited effect. In London, where a pro-Saudi line has been driven principally by Downing Street, there is growing unease over the impact of the blockade.

A Foreign Office spokesman said the UK “urges the coalition to quickly move to targeted naval interdictions of incoming commercial ships”.

“The UK remains in close contact with the government of Yemen and other international partners regarding the situation in Yemen, including the maritime blockade. The foreign secretary discussed Yemen with the Saudi foreign minister while in Paris this week,” the spokesman said.

“We are not participating directly in military operations, but are providing support to the Saudi Arabian armed forces through pre-existing arrangements. A small number of UK personnel are coordinating planning support with Saudi and coalition partners. All UK military personnel have extensive training on International Humanitarian Law.”

The Saudi government did not respond to requests for comment.

The blockade – which is also being enforced in the air and on land – has choked a fragile economy already staggering under the impact of a six-month civil conflict pitting Yemeni forces loyal to the President Abd-Rabbu Mansour Hadi, now exiled in Riyadh, against Houthi rebels allied to his predecessor and rival, Ali Abdullah Saleh.

A coalition led by Saudi Arabia and including Egypt, Jordan, Sudan and Bahrain intervened in March in support of Hadi, viewing the Houthis as an Iranian proxy force. Iran denies accusations of supplying arms to the insurgents, but British officials believe there are Iranian Revolutionary Guard advisers with the Houthi rebel leadership.

Over 2,000 Yemeni civilians are known to have been killed in the fighting so far, and, according to new UN figures, a million have been forced from their homes. The humanitarian crisis meanwhile, affects the overwhelming majority of the population. Tankers carrying petrol, diesel and fuel oil are also being stopped routinely by the naval blockade, crippling the country’s electricity supply and forcing the mass closure of hospitals and schools. Most urgently, it has stopped water pumps working. Oxfam reckons the fighting and embargo have led to 3 million Yemenis being cut off from a clean water supply since March, bringing to 16 million the total without access to drinking water or sanitation – nearly two-thirds of the population – with dire implications for the spread of disease.

Cooking gas is almost impossible to find. Queues to refill gas cylinders in Sana’a now last for than a week, with people camping out by their cylinders or chaining them down to keep their place in the queue. There are also long lines of abandoned cars waiting for elusive supplies of petrol.

The UN estimate that nearly 20 million Yemenis are in need of humanitarian assistance – 78% of the entire population – represents an increase of 4 million since the escalation of the conflict with the Saudi intervention in March. Twelve million Yemenis are “food insecure”, having to struggle to find their next meal, up 1.4 million since March. Five million are described as “severely food insecure”, meaning they often go for days without a meal.

In the cities worst hit by street fighting, such as Aden, civilians are either cowering at home to avoid sniper fire and bombardment or have joined the more than half million Yemenis forced out of their houses and now looking for food and shelter. But the blockade has spread the impact of the humanitarian crisis around the country.

According to Save the Children, hospitals in at least 18 of the country’s 22 governorates have been closed or severely affected by the fighting or the lack of fuel. In particular, 153 health centres that supplied nutrition to over 450,000 at-risk children have shut down, as well as 158 outpatient clinics, responsible for providing basic healthcare to nearly half a million children under five. At the same time, due to lack of clean water and sanitation, cholera and other diseases are on the rise. A dengue fever outbreak has been reported in Aden.

“Children are dying preventable deaths in Yemen because the rate of infectious diseases is rising ,” said Priya Jacob, Save the Children’s director of programmes in Yemen. “The humanitarian crisis in Yemen is a protracted and rapidly deteriorating situation that leaves four out of five Yemeni people in need of aid. The ongoing naval and air blockade means very little aid is getting through, exacerbating the needs of the Yemeni people.”

“The lack of fuel is a real issue – both for our teams and for local people, making it difficult to transport patients and medical supplies,” said Ahmad Bilal, medical coordinator for Médecins sans Frontières based in Yemen’s third city, Taiz. “For ordinary people it means that it is hard to move around the city and it’s an ongoing struggle to access clean water and food. Many people living in frontline areas are unable to travel to clinics or hospitals for medical care both because of the fighting and the lack of fuel. Even those who are able to make it to health facilities find that they are not functioning. At least 12 hospitals in Taiz had to close their doors and stop receiving patients, for these reasons.”

A shipping source in Al Hudaydah said the flow of ships into Yemen was down 75% compared with before the March intervention.

“Some ships have been docked in the past week or so, but many others have been stopped and it’s hard to see any pattern. Sometimes the coalition conducts a search and sometimes it doesn’t. Sometimes it depends which navy is involved. In the past few days the Saudis have been more flexible, but the Egyptians have been rigid, not letting anything through,” the shipping source said.

The uncertainty has made some ship owners nervous about having their vessels impounded. Over the past few days, two tankers carrying 70,000 tonnes of diesel, steered away from the Yemen coast and have begun offloading the fuel into small ships offshore. But as of this week, less than a tenth of the country’s monthly fuel requirement of 5m tonnes is getting through the blockade.

“We have heard a lot about international commitments to help Yemen with big sums but we haven’t seen anything here,” Oxfam’s Nuha Abdul Jabber added. “This is the moment for the world to understand the severity of the situation.”

Julian Borger is the Guardian’s diplomatic editor. He was previously a correspondent in the US, the Middle East, eastern Europe and the Balkans. His book on the pursuit and capture of the Balkan war criminals, The Butcher’s Trail, will be published by Other Press (NY) in January 2016

5 June 2015