By Rima Najjar

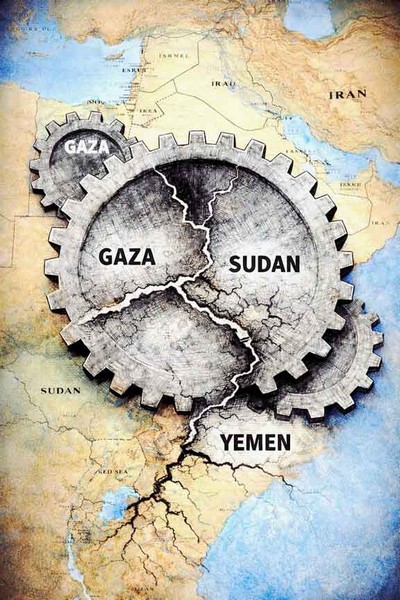

For most observers, the Middle East reads as chaotic noise — disconnected wars, perpetual emergencies. Yet from Palestine, a clear pattern emerges: a unified U.S.–Israel–anchored military-diplomatic order orbits one unresolved core — the political status of Palestine — while fueling conflicts across the region.

Gaza serves as the system’s primary template and proving ground.

Unlike the civil wars in Sudan and Yemen — internal non-international armed conflicts (NIACs) between rival domestic factions vying for state control — Gaza is not a civil conflict. It constitutes an international armed conflict rooted in Israel’s ongoing occupation and effective control over blockaded territory (as affirmed by the ICJ’s 2024 Advisory Opinion and subsequent rulings), involving direct state-to-non-state hostilities between Israeli forces and Palestinian armed groups.

This structural asymmetry and occupation framework make Gaza the system’s most transparent and intensely monitored proving ground, where direct field-testing of weapons, near-absolute diplomatic shielding, and systematic civilian harm expose the machinery with exceptional clarity.

A single integrated ecosystem of arms manufacturers, financiers, and logistics sustains the violence in Gaza, Yemen, and Sudan through shared supply chains, entrenched impunity, and a calculus that deems civilian lives expendable. Diplomatic failures — vetoed UN resolutions, blocked sanctions, uninterrupted arms flows — signal to all actors that brutality carries no enforceable price. Here, the United States and United Kingdom field-test weapon systems (often marketed as “battle-tested” post-Gaza); Washington and London deploy near-unrestrained diplomatic shields; and regional powers — Saudi Arabia, UAE, Egypt, Turkey, Iran, Qatar — reinforce the collapse of international law.

In response, Palestine-focused activists have become forensic analysts of this architecture: mapping supply chains (e.g., tracing Elbit Systems’ UK factories, whose disruptions contributed to site closures like Aztec West in September 2025 after products appeared in Gaza), tracking veto patterns, and extending this knowledge to Yemen, Sudan, and beyond.

These wars are bound into one regional system through three interlocking layers of power.

Layer One: The U.S.–Israel Axis

At the core lies the enduring confrontation between the U.S.–Israel axis and Iran. Iran sustains armed groups resisting dominance without formal alliances, while the U.S. and Israel bolster their stance through massive military aid, diplomatic cover, and strategic partnerships. This dynamic shines clearest in Palestine, yet it extends outward, shaping conflicts in Yemen and Sudan.

Gaza exposes the mechanics plainly. The United States props up Israel’s military freedom and shields it diplomatically. Israel wields direct coercive force over Palestinians. Iran, in turn, arms groups that challenge Israeli control.

The pattern intensifies in Yemen, escalating to open warfare. Houthis fire missiles and drones at ships linked to Israel’s Gaza operations — including those hauling arms — prompting retaliatory strikes from the U.S., UK, and Israel on Yemeni soil. Israel conducted repeated airstrikes on Houthi targets throughout 2025 (targeting ports, airports, and leadership in Sanaa and Hodeidah), though both sides paused direct exchanges after the October Gaza ceasefire.

In Sudan, the axis operates more covertly, but with equal strategic weight. Israel avoids direct strikes yet views the country as vital to its Red Sea map: maintaining intelligence networks, pursuing normalization (stalled since 2020–2023 efforts), and monitoring alleged Iranian smuggling routes to Gaza — routes long cited by Israeli and Western sources to justify surveillance. Iran’s renewed ties with Khartoum since 2023, including drone supplies to the Sudanese Armed Forces, alongside Gulf alignments with Washington, influence how powers back the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) or Rapid Support Forces (RSF). Far from purely internal, these wars orbit the Gaza-centered clash, drawn inexorably into its pull.

Layer Two: The Saudi–UAE Rivalry

A second layer overlays the region: the intense competition between Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. This rivalry — fought over ports, militias, airbases, and political leverage — shapes outcomes in states hollowed out by war, determining who controls key assets in Yemen and Sudan.

Neither intervenes directly in Gaza militarily, yet both carefully calibrate their stances — from humanitarian aid and reconstruction pledges to public rhetoric and deliberate silences — primarily to bolster their influence in Washington, Tel Aviv, and the broader Arab world. By early January 2026, this rivalry had spilled into open confrontation in Yemen: Saudi-led coalition airstrikes struck UAE-linked arms shipments and separatist positions at Mukalla port in late December 2025 and in Hadramout, followed by UAE troop withdrawals and open accusations that Saudi actions endangered Emirati forces — laying bare the volatility and fragility of Gulf alignments.

In Yemen, the rivalry structures the conflict itself. Saudi Arabia arms and backs the internationally recognized government, aiming for a unified state. The UAE, by contrast, cultivates southern militias — particularly the Southern Transitional Council (STC) — to secure coastal influence and fragment authority into rival zones. Emirati logistical networks supply these forces while simultaneously arming the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in Sudan, illustrating how one set of supply chains sustains parallel wars.

Sudan sees a quieter but no less pivotal version of the same dynamic. The UAE provides the RSF with arms (including drones, vehicles, and ammunition, often via proxies or breaches of UN embargoes, as alleged in ongoing 2025–2026 reports). Saudi Arabia, alongside Egypt, offers diplomatic, financial, and military backing to the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), prioritizing stability along the Red Sea. Each power injects its own agenda: securing maritime corridors, gold/agricultural access, countering political Islam (a UAE priority), and aligning Sudan with U.S./Israeli Red Sea interests.

The result is that Sudan’s institutions are reorganized around external strategic demands rather than national needs: militarization deepens, civilian governance is weakened, and territorial fragmentation becomes politically acceptable to external powers and their regional partners so long as they retain secure access to ports, corridors, and resource flows.

Across both theaters, Gulf competition reinforces local militaries, entrenches external priorities, and perpetuates division — turning dysfunctional states into arenas for proxy influence.

Layer Three: Evasion in a Multipolar Order

The third layer emerges from the erosion of a U.S.-dominated regional order toward multipolarity. States and armed groups now routinely evade sanctions, diplomatic pressure, accountability mechanisms, and conditional aid by cultivating multiple patrons — each providing distinct forms of protection, from weapons and funding to political cover and sanctions relief.

In Sudan, this evasion has become a core survival tactic. The SAF draw support from Egypt (diplomatic and military backing, driven by Nile security), Russia (arms and potential naval base access at Port Sudan), Iran (drones and other supplies), and Turkey — a mix that shields them from full isolation. The RSF, meanwhile, rely heavily on the UAE (alleged arms deliveries, including drones and vehicles, often via covert routes despite denials), alongside sporadic ties to Russia (via Wagner/Africa Corps networks) and others. These overlapping patrons allow both sides to procure weapons, finance operations, and deflect consequences, prolonging the conflict amid a fractured global response.

Yemen mirrors this pattern even more deeply embedded in daily operations. The Houthis lean on Iran for advanced weaponry and financial lifelines (despite UN arms embargoes), use Omani mediation channels for diplomacy, and leverage control of Red Sea shipping lanes to generate revenue and blunt external pressure. Southern factions, particularly those aligned with the Southern Transitional Council (STC), depend on the UAE for military and financial sustainment, while Saudi Arabia provides backing to the internationally recognized government. Each actor secures a patron capable of offsetting sanctions, supplying arms, or blocking punitive measures — turning evasion into a structural feature of the war.

This diffusion of leverage does not diminish Washington’s enforcement power so much as reveal its selective restraint. The persistent lack of consequences in Gaza — even after the October 2025 ceasefire — sends a clear regional message: no major power, East or West, consistently imposes meaningful limits on belligerents. Armed actors in Sudan and Yemen draw the obvious lesson, operating with calculated impunity.

Together, these three layers — confrontation (U.S.–Israel–Iran), rivalry (Saudi–UAE), and evasion (multipolar shielding) — constitute a unified regional war-making architecture. Gaza remains the most transparent proving ground; Yemen the militarized spillover where direct clashes unfold; Sudan the competition arena where alignments and rivalries reshape the state, driving militarization, fragmentation, and governance oriented toward external imperatives.

What appear as isolated crises are, in reality, varied manifestations of the same system: intertwined supply chains, cross-cutting alliances that pit the same states against each other in different theaters, and mechanisms of external control that render civilian suffering strategically tolerable.

Sudan: A State Split Into Two Armed Machines

Sudan’s civil war erupted on 15 April 2023 between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), led by Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), commanded by Mohamed Hamdan “Hemedti” Dagalo. Rooted in internal fractures — competition over force integration, Darfur’s gold fields, ethnic tensions, and systematic civilian violence described as genocidal — these cleavages long predated regional involvement. Yet the current order ensures they cannot remain internal. External networks of arms pipelines, political shielding, and diffused veto points amplify the conflict, rewarding brutality with near-total impunity.

Sudan occupies a pivotal spot in the Red Sea control system linking Gaza, Yemen, and the Horn of Africa. Israel’s involvement stays strategic rather than direct military: intelligence ties persist, normalization efforts (2020–2023) linger in memory, and monitoring of alleged Iran-linked weapons-smuggling routes to Gaza keeps Sudan tied to the U.S.–Israel–Iran confrontation. Netanyahu’s past UN references to Sudan as a “friend” highlighted this interest. For Sudan’s ruling institutions, this geography makes Iranian alignment both tactically useful and strategically dangerous, inviting Israeli and Western retaliation and jeopardizing Gulf backing. For external powers and their regional partners, the country’s collapse becomes politically tolerable so long as the Red Sea corridor and associated ports and transit routes remain secure from Iran-aligned groups.

The U.S.–Israel–Iran triangle and Saudi–UAE rivalry exert powerful gravitational force. The UAE has faced persistent allegations of arming the RSF — including armored vehicles, drones, and other equipment (often via covert channels or proxies, breaching UN embargoes) — while Saudi Arabia and Egypt provide diplomatic, financial, and military support to the SAF. These patterns mirror their competing architectures in Yemen. Gulf competition hardens local militaries, sidelines civilian authority, and reorients Sudan’s institutions toward external priorities: control of Red Sea ports, access to gold and agricultural land, countering political Islam (a UAE focus), and alignment with U.S./Israeli Red Sea interests.

Civilian infrastructure turns into deliberate battlefield targets: hospitals, markets, water points, and transport routes face systematic attacks or militarization. The RSF’s 18-month siege of Al-Fashir (El Fasher) in North Darfur culminated in the city’s fall in late October 2025, unleashing mass killings, detentions, executions, and the destruction of basic services — leaving it nearly devoid of life and sparking mass exodus. Famine conditions (IPC Phase 5) persist in El Fasher and Kadugli through at least January 2026, driven by sieges, restricted access, market collapse, and ongoing violence. With over 12 million people displaced (UNHCR figures as of late 2025, including trends into early 2026) — making Sudan the world’s largest displacement crisis — the country exemplifies how local violence, fused with regional competition and global impunity, delivers predictable state collapse.

Yemen: A Long War Rewired by the Regional Machine

Yemen’s conflict began with internal fractures: the 2014 Houthi takeover of Sanaa amid widespread economic grievances, compounded by enduring north–south divides that continue to fuel separatist demands. These divides trace back to Yemen’s pre-1990 history as two separate states — the tribal-influenced, conservative North Yemen centered in Sana’a and the Marxist, secular South Yemen with Aden as its capital — whose rushed 1990 unification led to northern dominance, southern marginalization, economic neglect, and the failed 1994 secession attempt, entrenching grievances that birthed the Southern Movement (al-Hirak) from 2007 onward.

The Southern Transitional Council (STC)’s rapid December 2025 offensive — codenamed “Promising Future” — seizing control of much of Hadramout (including oil-rich facilities, Seiyun, Tarim, and key sites), al-Mahra (including the capital Al Ghaydah and Nishtun port), and other southern territories without major resistance demonstrates these rifts remain active and potent. By early December, UAE-backed STC forces had swept through eastern provinces, reaching Oman’s border and controlling most of the former South Yemen territory (Aden, Lahij, Dhale, Abyan, Shabwah, Hadramout, al-Mahra, Socotra), often against fragmented Saudi-backed government troops.

This advance has deepened Yemen’s de facto partition along north–south lines, creating rival authorities, currencies, and armed forces. In the north, Iran-backed Houthis maintain a separate administration in Sana’a with their own institutions, security apparatus, and economy. In the south, the STC dominates administration, security, and economic levers, operating via the Aden-based central bank, issuing banknotes, and pursuing independent monetary policies — resulting in rival currencies (with differing exchange rates, old vs. new notes, and Houthi rejection of post-2016 Aden-printed bills) and parallel economic systems. These developments underscore how the underlying north–south divide — rooted in historical separation, unequal unification, and persistent grievances — has evolved into parallel realities and a near-partition that overshadows any unified state vision.

Yet Saudi and Emirati intervention transformed Yemen from a domestic crisis into a theater reshaped by overlapping external networks. Saudi Arabia has long armed and supported the internationally recognized government, seeking a unified state. The UAE, in contrast, has cultivated southern militias — especially the STC — to secure coastal strongholds around Aden, Mukalla, and beyond. T

As noted before, the same Emirati logistical chains that supply these forces also arm the RSF in Sudan, showing how one rivalry powers multiple wars across the region. Rather than heal divisions, these interventions entrenched them: ministries split, revenue streams fragmented, and the currency divided. By 2025, Yemen functioned less as a unified state than as competing patronage zones anchored to external patrons.

Front-line clashes have eased, but the war has shifted to economic fronts — blocked salaries, rival customs systems, and fierce battles over ports and fuel. Diplomacy has reduced airstrikes without reversing fragmentation. More than 19 million people — over half the population — require humanitarian assistance and protection as the enduring baseline, with women, girls, IDPs, refugees, and migrants facing acute vulnerability amid ongoing economic warfare and service breakdowns.

The Red Sea crisis fully integrated Yemen into the U.S.–Israel–Iran confrontation. Houthis framed their maritime attacks as solidarity with Gaza, launching missiles and drones in rhythm with escalations there; U.S. responses aligned closely with Israeli threat assessments. Israel became a direct military actor, conducting repeated airstrikes on Houthi targets — most intensely from mid-2025 (targeting ports like Hodeidah, power stations, and leadership in Sanaa) — though both sides paused direct exchanges after the October 2025 Gaza ceasefire, with Houthis halting attacks on Israel and shipping (while reserving the right to resume if the truce breaks).

Saudi–UAE tensions exploded dramatically in late December 2025: Saudi-led coalition airstrikes targeted alleged UAE-linked arms shipments and military vehicles bound for STC separatists at Mukalla port (destroying trucks and equipment), followed by UAE troop withdrawals, public accusations of endangerment, and a brief cooling into early January 2026. This unprecedented escalation — including multiple strikes and warnings of threats to Saudi national security — exposed the rivalry’s volatility amid STC advances in Hadramout and al-Mahra, culminating in the STC’s January 2, 2026 announcement of a two-year transitional period toward southern independence. This includes a constitutional declaration for the “State of South Arabia” (capital Aden, based on pre-1990 borders) and a planned referendum on self-determination, with immediate independence possible if dialogue fails or attacks resume.

Like Sudan, Yemen stands far from peripheral to the Gaza-centered architecture. The Houthi Red Sea campaign, explicitly tied to Gaza solidarity, drew direct Israeli and U.S. military involvement, while the southern separatist surge — fueled by Gulf proxy rivalries — has further fragmented the country, complicating any unified response to regional threats. It serves as a frontline where confrontation, rivalry, and evasion converge: shared supply chains drive fragmentation, external priorities eclipse national ones, and civilian collapse solidifies as the norm.

Civilian Collapse

This regional war-making architecture reliably generates civilian collapse — eroding essential services first, then markets, and ultimately demographics.

In Sudan, the breakdown manifests starkly: emptied cities, destroyed hospitals, missing detainees, and mass displacement on a historic scale. Famine conditions (IPC Phase 5) persist in El Fasher (North Darfur) and Kadugli (South Kordofan), with reasonable evidence confirming starvation-level food insecurity as of September 2025 and expectations that these conditions will continue through at least January 2026, according to the latest IPC analysis and Famine Review Committee conclusions. Immediate deaths blend into long-term devastation: extreme malnutrition (with Global Acute Malnutrition rates reaching 38–75% in El Fasher and 29% in Kadugli), widespread disease, educational collapse, mass trauma, and forced demographic shifts through displacement and mortality.

In Yemen, institutional decay appears in currency fragmentation, chronic unpaid salaries, restricted movement and trade, and persistent underfunding of aid. More than 19 million people — over half the population — require humanitarian assistance and protection as the baseline in 2025–2026, per OCHA and UNHCR assessments, with women, girls, IDPs, refugees, and migrants facing acute vulnerability amid ongoing economic warfare and service breakdowns.

These patterns directly mirror mechanisms long entrenched in Gaza and the West Bank: systematic targeting of civilian infrastructure, normalization of mass harm, and long-term demographic engineering. When brutality in one theater faces no enforceable consequences, it reduces the perceived cost of similar violence elsewhere, embedding impunity across the system.

The New Activism as Systems Practice

This is the grim reality that contemporary activists now confront head-on. Since 2023, solidarity movements have matured beyond moral outrage into a sophisticated systems practice. They no longer ask whether the wars are wrong; they systematically expose how they are sustained — and apply targeted pressure at the precise pressure points of the machinery.

Activists map weapons supply chains in detail: tracing components from factories to frontlines, exposing banks that finance them, ports that transport them, insurers that underwrite them, universities that research them, and corporations that profit. Palestine Action’s pre-proscription disruptions of Elbit Systems’ UK factories — which forced public scrutiny and contributed to site closures like Aztec West in September 2025 — exemplified this forensic approach, directly challenging the supply lines feeding Gaza’s destruction.

These efforts transform ordinary infrastructure into contested terrain. Dockworkers across Europe — from France’s Fos-Marseille (June 2025 blockade of arms components) to Italy’s Genoa (multiple 2025 actions, including inspections and refusals on ZIM-linked ships), as well as ports in Sweden, Greece, and beyond — have refused to handle military cargo bound for Israel, responding to calls from Palestinian trade unions and generating immediate logistical friction. Banks reassess reputational and legal risks; universities cut ties to surveillance technologies; courts turn into arenas for injunctions, liability suits, and challenges to complicit transfers.

What emerges is not just narrative shift, but tangible friction: shipment delays, elevated risks for financiers, reputational damage for corporations, legal uncertainty for enablers, and rising financial costs for the war machine. This activism does not end wars through moral appeals alone; it constrains and slows them by disrupting the infrastructure that sustains them.

Yet friction cannot dismantle a system designed to neutralize resistance. The state’s juridical shield — anti-terror laws, proscriptions, diplomatic vetoes — activates rapidly when threatened. The July 5, 2025, proscription of Palestine Action under the Terrorism Act (following the earlier proscription of Samidoun) demonstrated this protective coherence. As of early 2026, the ban remains in force, but a landmark judicial review — heard over three days in late November/early December 2025, with interventions from Amnesty International UK, Liberty, and UN experts — contests it as a disproportionate violation of free expression, assembly, and protest rights under Articles 10, 11, and 14 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Judgment remains pending, even as mass defiance continues: over 2,000 arrests (many for simply holding signs stating “I oppose genocide, I support Palestine Action”), hunger strikes by imprisoned activists demanding the ban’s reversal, and broad condemnation from civil liberties groups as Orwellian overreach.

Boycotts, blockades, and supply-chain disruptions have raised costs and slowed arms flows, yet systemic transformation stays elusive amid entrenched financing, UN vetoes, and legal fortifications. The region remains locked in managed catastrophe: external powers sustain their rivalries by fueling perpetual internal collapse.

For the first time in decades, however, this lethal equilibrium encounters sustained resistance from a new activism that targets the logistical and financial core directly. Activists recognize that halting the wars requires disrupting the machine — even in the face of repression, arrests, and daunting setbacks.

Everything connects.

Every component, from the bank to the bomb, has a function.

Everything has a cost.

And for millions across Gaza, the West Bank, Yemen, and Sudan, that cost is measured in life itself.

Rima Najjar is a Palestinian whose father’s side of the family comes from the forcibly depopulated village of Lifta on the western outskirts of Jerusalem and whose mother’s side of the family is from Ijzim, south of Haifa.

4 January 2026

Source: countercurrents.org