By Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja

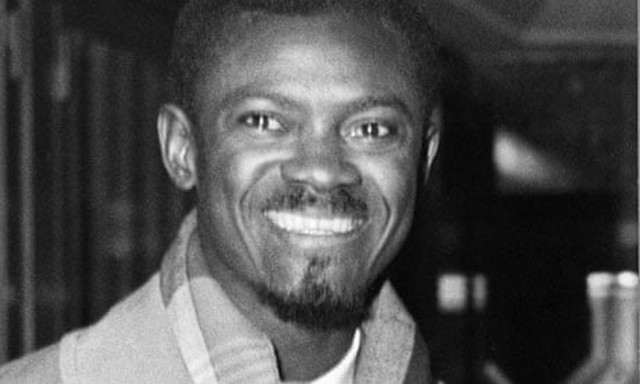

Patrice Lumumba, the first legally elected prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), was assassinated 50 years ago today, on 17 January, 1961. This heinous crime was a culmination of two inter-related assassination plots by American and Belgian governments, which used Congolese accomplices and a Belgian execution squad to carry out the deed.

Ludo De Witte, the Belgian author of the best book on this crime, qualifies it as “the most important assassination of the 20th century”. The assassination’s historical importance lies in a multitude of factors, the most pertinent being the global context in which it took place, its impact on Congolese politics since then and Lumumba’s overall legacy as a nationalist leader.

For 126 years, the US and Belgium have played key roles in shaping Congo’s destiny. In April 1884, seven months before the Berlin Congress, the US became the first country in the world to recognise the claims of King Leopold II of the Belgians to the territories of the Congo Basin.

When the atrocities related to brutal economic exploitation in Leopold’s Congo Free State resulted in millions of fatalities, the US joined other world powers to force Belgium to take over the country as a regular colony. And it was during the colonial period that the US acquired a strategic stake in the enormous natural wealth of the Congo, following its use of the uranium from Congolese mines to manufacture the first atomic weapons, the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs.

With the outbreak of the cold war, it was inevitable that the US and its western allies would not be prepared to let Africans have effective control over strategic raw materials, lest these fall in the hands of their enemies in the Soviet camp. It is in this regard that Patrice Lumumba’s determination to achieve genuine independence and to have full control over Congo’s resources in order to utilise them to improve the living conditions of our people was perceived as a threat to western interests. To fight him, the US and Belgium used all the tools and resources at their disposal, including the United Nations secretariat, under Dag Hammarskjöld and Ralph Bunche, to buy the support of Lumumba’s Congolese rivals , and hired killers.

In Congo, Lumumba’s assassination is rightly viewed as the country’s original sin. Coming less than seven months after independence (on 30 June, 1960), it was a stumbling block to the ideals of national unity, economic independence and pan-African solidarity that Lumumba had championed, as well as a shattering blow to the hopes of millions of Congolese for freedom and material prosperity.

The assassination took place at a time when the country had fallen under four separate governments: the central government in Kinshasa (then Léopoldville); a rival central government by Lumumba’s followers in Kisangani (then Stanleyville); and the secessionist regimes in the mineral-rich provinces of Katanga and South Kasai. Since Lumumba’s physical elimination had removed what the west saw as the major threat to their interests in the Congo, internationally-led efforts were undertaken to restore the authority of the moderate and pro-western regime in Kinshasa over the entire country. These resulted in ending the Lumumbist regime in Kisangani in August 1961, the secession of South Kasai in September 1962, and the Katanga secession in January 1963.

No sooner did this unification process end than a radical social movement for a “second independence” arose to challenge the neocolonial state and its pro-western leadership. This mass movement of peasants, workers, the urban unemployed, students and lower civil servants found an eager leadership among Lumumba’s lieutenants, most of whom had regrouped to establish a National Liberation Council (CNL) in October 1963 in Brazzaville, across the Congo river from Kinshasa. The strengths and weaknesses of this movement may serve as a way of gauging the overall legacy of Patrice Lumumba for Congo and Africa as a whole.

The most positive aspect of this legacy was manifest in the selfless devotion of Pierre Mulele to radical change for purposes of meeting the deepest aspirations of the Congolese people for democracy and social progress. On the other hand, the CNL leadership, which included Christophe Gbenye and Laurent-Désiré Kabila, was more interested in power and its attendant privileges than in the people’s welfare. This is Lumumbism in words rather than in deeds. As president three decades later, Laurent Kabila did little to move from words to deeds.

More importantly, the greatest legacy that Lumumba left for Congo is the ideal of national unity. Recently, a Congolese radio station asked me whether the independence of South Sudan should be a matter of concern with respect to national unity in the Congo. I responded that since Patrice Lumumba has died for Congo’s unity, our people will remain utterly steadfast in their defence of our national unity.

Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja is professor of African and Afro-American studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and author of The Congo from Leopold to Kabila: A People’s History

17 January 2011

Source: www.theguardian.com