By Hugh Turley

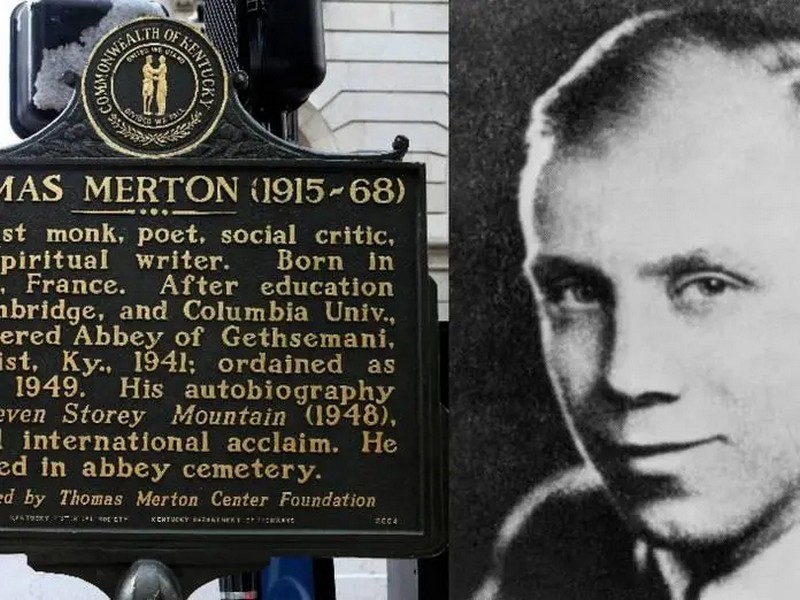

8 Jul 2024 – Thomas Merton was the most influential Catholic writer of the 20th century.

He was almost as well-known in the United States as the author Ernest Hemingway or the popular Bishop Fulton J. Sheen.

He had been raised in France where his American mother and New Zealander father had met in a Paris art school, and he was educated as a teenager at a boarding school in England. After a wasted year at Cambridge, he had gone on to Columbia, near his prosperous grandparents’ home.

Shortly after his graduation in 1938, while working on his M.A. in English, he became a Catholic. He interrupted his work toward a Ph.D. to pursue a religious vocation, entering a Trappist monastery just a few days after the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. He remained at the Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky until his death in 1968.

A voracious reader and always interested in writing, Merton, encouraged by his first abbot, Frederic Dunne, continued his career as a writer at the monastery, getting books of his poetry published. Then Dunne suggested that he write a book about his eventful and tragic young life.

His mother had died when he was very young, his father had died when he was a boarding student, and his younger brother, his only sibling, had been killed in an accident as a member of the Canadian Air Force in World War II.

The resulting book, The Seven Storey Mountain, became a surprising overnight sensation. He continued writing, and during the 1950s and 1960s, almost every Catholic home in America owned books by Thomas Merton.

In the 1960s his writing turned political, as he wrote about civil rights and non-violence, warning that the press was responsible for promoting wars. If Merton had lived, there is a good chance that he would have become the leading Catholic voice against the Vietnam War.

In 1968, three prominent advocates for peace died under questionable circumstances: Martin Luther King, Jr., Robert F. Kennedy, and Thomas Merton. It was the last full year of Lyndon Johnson’s presidency. King and Kennedy were publicly assassinated, with the identity of their assassin or assassins continuing to remain in doubt, regardless of the press-endorsed lone-crazed-gunman official verdict. Merton’s secret assassination was covered up as an accident. The cover-up succeeded for a half-century.

On December 10, 1968, at around 4:00 p.m. at a cottage at the Red Cross retreat center near Bangkok, Thailand, where they were attending a Catholic monastic conference, three Benedictine monks found Thomas Merton’s body when they entered his room. Abbot Odo Haas, Archabbot Egbert Donovan, and Father Celestine Say immediately recognized that Merton was dead.

Say’s room was just across the hall, and the scene was so odd that Donovan encouraged him to get his camera and photograph what they saw. Say took two photographs of the body just as they had found it. Say intended to give the photographs to the Thai police, but it quickly became clear to him that the police were not doing a proper investigation.

As we can see, Say took his two photographs of Merton’s body from different angles. He later said that he did not tell the police about the photos because he thought that they might confiscate his film and camera. After the film was developed, he sent one of the photographs (the other was underexposed) and a letter on March 18, 1969, to Merton’s Gethsemani Abbey in Kentucky.

Burning with curiosity over the odd death scene, Say asked Abbot Flavian Burns if there had been an autopsy to determine the cause of Merton’s death before his burial. The abbot, in fact, had not ordered an autopsy and none had been done, although the doctor’s certificate and the death certificate affirmed that a “post-mortem examination” had been done in accordance with the law.

Abbot Flavian shared Say’s photograph with John Howard Griffin. Griffin, a frequent visitor to the abbey and famous for his civil rights book, Black Like Me, had been authorized by the abbey to be Merton’s biographer.

Griffin immediately recognized the significance of Say’s photographs and joined Abbot Flavian and Merton’s recently named secretary, Brother Patrick Hart, in an effort to secure the film negatives from Say. They praised Say for taking the important pictures and asked him to send them the negatives so that they could be “protected.” Say sent his negatives to the abbot as a gift. The negatives became the property of the Abbey of Gethsemani.

Griffin advised Abbot Flavian and Brother Patrick that the negatives should never be published or available to anyone. What did the Benedictine monks see that prompted them to take photographs of Merton’s body? Why was it deemed necessary at the abbey that these photographs be hidden from the public?

The Associated Press had reported on December 11, 1968, the day after the death, that Merton “was electrocuted Tuesday when he moved an electric fan and touched a short in the cord.” Their source was not the official Thai investigating authorities but rather anonymous “local Catholic sources.” The Gethsemani Abbey quickly echoed the AP conclusion and has adhered to it to the present day.

In 2017, we discovered Say’s negatives in the papers of John Howard Griffin at the Butler Library of Columbia University and quickly realized why they had been hidden. With modern technology we were able to get the underexposed negative developed, and the two photographs reveal what looks very much like a crime scene that had been staged to appear as an accident.

The first thing that the witnesses noticed was the unnatural position of the body. They saw Merton lying flat on his back with his arms straight by his side. People don’t fall like that. And how in the world did the fan, well free of his hands, get across his body? His body had electrical burns, but his hands did not. It looks as though Merton had been rolled over onto his back by someone else. The rolling would have required that his arms be by his side.

Vernon Geberth, author of Practical Homicide Investigation, writes that, “if you have a gut feeling that something is wrong, then, guess what? Something is wrong.” The initial gut feeling of the first witnesses was that things were not what they appeared to be. That was why Donovan had Say take the photographs.

The abbey not only concealed the photographs, but they concealed the official Thai reports. Officially, Merton died of a natural cause. Contrary to the AP report, the Thai police, while deceptively noting the presence of the defective fan, had concluded that Merton had died of “heart failure” and that he was already dead before he encountered the fan. Hardly anything could be more absurd. Like the fan that had been effectively cooling Merton’s room, this defective one had been manufactured by the reliable Hitachi company.

Some of the muddled descriptions of Merton’s death came from his former abbot, James Fox. Fox wrote that Merton had been electrocuted by a faulty wire in a large fan in his room. According to Fox, Merton either had a heart attack and grabbed the fan and it fell with him, or he grabbed the fan and it fell with him, or he had been fixing the fan and grabbed a badly insulated wire.

The staged scene left the public to debate whether the cause of death was an accident or a natural cause. The placement of the fan by the perpetrator directed attention away from a head wound seen by witnesses.

The final authorized biographer, Michael Mott, who took over for Griffin when Griffin became too ill to continue, in The Seven Mountains of Thomas Merton revealed that the wound, which was in the back of Merton’s head, had “bled considerably.” In his next sentence Mott writes, “The obvious solution appears to be that it was caused when his head struck the floor.” It is important to point out that neither the Thai police investigators nor anyone in the press made any mention of that bleeding head wound.

Was it obvious to Mott, or did that just appear to be the cause of the long-bleeding wound? Can anyone imagine a person falling backward onto a level floor receiving such a wound? It is very doubtful that Geberth, a long-time homicide investigator for the New York City Police Department, would have seen anything obvious about it.

Say’s photographs were hidden for additional reasons. The photographs prove that Merton’s abbey knowingly spread false information. On December 19, 1968, the abbey circulated a suspicious unsigned letter from a group of conference attendees in response to requests for more details about Merton’s death. The letter stated that it was difficult at that time to determine the cause of Merton’s death and then it speculated that Merton may have had a heart attack or suffered a fatal electric shock.

Detective Geberth tells us that ambiguity is one of the features of a staged crime scene, and it is hard to get any more ambiguous than that. The letter also had several errors of fact, for example, that Merton “could have showered” and that a fan was found “lying across his chest.” The letter accurately stated, though, that Merton was found “in his pajamas.”

In 1973, the abbey shared the letter with a wider audience when it was published in a book, The Asian Journal of Thomas Merton. The book included a description of Merton’s death by Br. Patrick, who wrote in the postscript that Merton had taken a shower before his “accidental electrocution.” The three words, “in his pajamas,” were removed in the copy of the letter published as an appendix. Those pajamas had no place alongside Brother Patrick’s shower story.

Brother Patrick was working closely with the two other editors of The Asian Journal of Thomas Merton, Merton’s New York literary agent, Naomi Burton Stone, and his New York publisher, James Laughlin. All three of them knew about the photograph of Merton in his pajamas, so they had to have known that the shower story was not true. Witnesses in the cottage where Merton died also said that he did not take a shower.

After the abbey received Say’s photograph, the abbey continued to state that Merton’s chest had been burned deeply by the fan found lying across his chest. A wound on the chest would suggest that it had something to do with the heart failure. Say’s pictures prove that there was no such burn on the chest.

In 1967 Merton had signed an agreement to create the Merton Legacy Trust, to ensure that his valuable literary estate would belong to the abbey in the event of his death. Hardly a year had passed before Merton was dead. The three original members of the trust included Stone, Laughlin and Merton’s good friend Thomasine “Tommie” O’Callaghan. Only a few people knew about the secret photographs. Stone and Laughlin agreed with Brother Patrick and Griffin to keep the photos a secret from O’Callaghan.

On July 24, 1969, Griffin warned Brother Patrick that O’Callaghan suspected that the abbey was keeping things hidden from her. Griffin advised Brother Patrick to “be as bland and dumb as possible…sending her the vaguest answers.” On August 19, 1969, Stone wrote to Griffin that O’Callaghan was “a hazard we shall just have to live with,” adding that she disliked “the necessity of keeping things from [O’Callaghan] (which I feel is essential and I know [Laughlin] agrees)…” Stone, Griffin and others admitted that they burned and destroyed letters to each other, but a few of their letters have survived.

One obstacle to the truth being known has been the charming, likable nature of Brother Patrick. Many people remember him fondly, making it difficult for them to accept the very solid evidence that he contributed to the cover-up of Merton’s assassination. Brother Patrick had an unwavering loyalty to the abbey and especially to his former abbot James Fox, a central figure in the cover-up. Fox was responsible for the story that the fan was found lying on Merton’s deeply burned chest. Brother Patrick had seen Say’s photograph with the fan across the pelvis and no burns on the chest, so his participation in that lie can be added to his invention of the shower story among his major contributions to the cover-up.

There is popular photograph of Brother Patrick and Merton together. It cements in the public mind the false impression that Merton and Br. Patrick were friends. The photograph was taken on the day of Merton’s departure from Gethsemani. In the original picture, Br. Maurice Flood is standing on the left side of Merton. Flood was also a secretary to Thomas Merton, but Flood is frequently cropped out of this photograph.

The place where Merton died is significant. In 1968, the Phoenix Program, an assassination operation run by the CIA, was active in Thailand and the agency worked closely with corrupt Thai officials. The U.S. government has admitted committing about 20,000 assassinations in Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War. The Vietnamese estimate the number is closer to 40,000.

Thomas Merton, the peacemaker, was an incorruptible force challenging the propaganda news media and warfare state. Killing Merton in Thailand would have been business as usual for the CIA assassins.

The only possible problem might have come from Merton’s surrogate family at the Abbey of Gethsemani. The killers had to know in advance that they would have no more problem from Merton’s abbey than with the Associated Press, The New York Times, and all the others. That proved to be the case in spades. Had the abbey really cared about knowing the truth, they would have insisted that an autopsy be performed. They did not. The abbey also hid Say’s photograph and the official Thai reports, and they seemed to do everything in their power to persuade the public that Merton had died of a tragic, though bizarre, accident.

Hugh Turley as a volunteer columnist for the Hyattsville Life and Times, is winner of the National Newspaper Association award for best serious column, small-circulation, non-daily division.

5 August 2024

Source: transcend.org