By Rama Sundari

On August 5, 2019, a wound was carved into Kashmir’s history that refuses to heal. In a move carried out without the consent of its people, the region was stripped of its autonomy and statehood -rights enshrined for decades in the Indian Constitution. Since that day, Kashmir has become an open-air prison. Freedoms have been dismantled one by one. Journalists are muzzled, news is blacked out, human rights defenders are jailed, and every independent rights organisation in the valley has been shut down. What passes for democracy are hollow elections -staged performances meant to pacify public anger while masking the suffocation of an entire people.

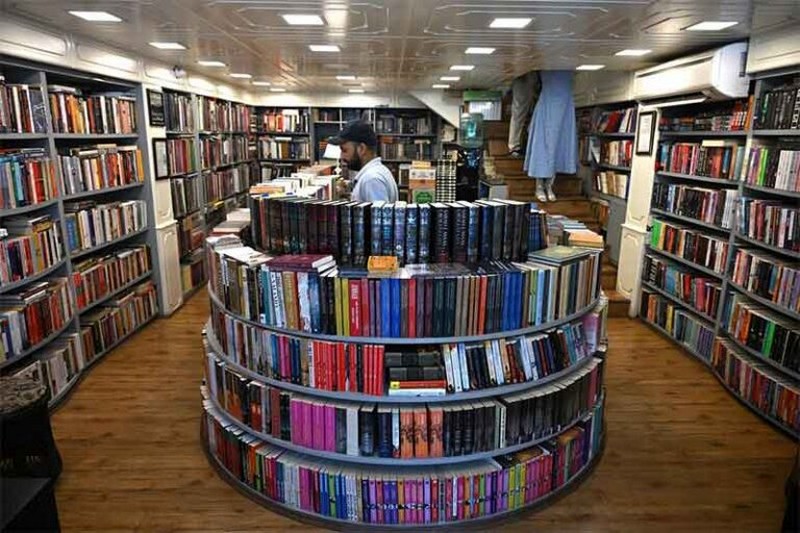

Six years later, on that same date, grief returned in a different form. This time, the weapon was not soldiers or barbed wire, but ink and paper -a ban on 25 books about Kashmir. Setting aside the truth that banning books is an assault on democracy itself, the question remains: why, specifically, are books on Kashmir being targeted now?

The answer is blunt and undeniable: they want to bury Kashmir’s truth. By crafting false narratives to overwrite its complex and painful history, they strip away every trace of sympathy from the mainland’s conscience if any leftover exists. The horrors before and after August 5, 2019, are to be not only forgotten but justified. It is a calculated attempt to begin anew on a blank page where the past is forbidden to exist.

Since 2021, authentic news from the valley has all but disappeared. With the flow of information choked, the people of Kashmir -and those who care deeply about it -have turned to books as their last refuge. In their pages, they find voices long silenced, truths that cannot be aired on censored television or printed in tightly controlled newspapers. These histories bring Kashmir back into the light, allowing readers to trace its past to understand its troubled present. And it is precisely this illumination that makes such books dangerous to those determined to erase the region’s rich and complex history.

As the state tightens its grip on the internet -criminalising even the mildest social media posts and unleashing organised troll mobs to crush dissent -many young people are walking away from these toxic platforms. They reclaim their time for more meaningful pursuits, turning to writing as one of the few refuges left where truth can still breathe. But now, the government turns its gaze toward writers and their words. It dares to ban books, branding them as enemies of the state -easy to criminalise, convenient to punish. In this war on ideas, the written page becomes a battleground, and every sentence a potential act of defiance.

What the banned books reveal

Every title on the banned list is more than a book -it is a record of truths the authorities would rather bury. They lay bare the centuries-long ordeal of a people crushed under successive rulers since the 16th century. They expose the justice denied to Kashmiris after 1947, unravel the political manoeuvres that birthed Article 370, and explain why the region was left to languish as a disputed territory. Page by page, they document how, in the decades following independence, political freedoms and social rights were dismantled in deliberate, calculated steps.

These books are not merely histories; they are indictments -and that is precisely why they have been silenced. In the shadow of the guns that guard Kashmir, these books open a door to a world of silenced pain -telling stories of youth and women scarred by visible wounds and the deep, invisible traumas that still haunt them. They speak of young men who left home and never returned, their fates sealed in unmarked graves scattered across the valley. They describe the chilling stillness of thoughts held hostage at gunpoint, where even an idea can be a crime. And they paint, with unflinching detail, how the abrogation of Kashmir’s autonomy caged entire people in an open-air prison, with the mountains as silent witnesses.

The voices they tried to erase

One such work Kashmir in Conflict: India, Pakistan and the Unending War, British writer Victoria Schofield traces the region’s complex history -from rule under various powers, to the partition of its territory after independence, to the political manoeuvres surrounding its accession to India. She examines the conditions that led to Kashmir’s special status and offers thoughtful proposals for peace.

This book is vital, carrying truths we can no longer afford to ignore. It unpacks the geopolitics surrounding the Kashmir dispute, examining the long-promised plebiscite and the nature in which it was envisioned by the United Nations -one that would be fair, just, and acceptable to the people of Kashmir. The solution proposed in the book to resolve the dispute is likely to provoke the ire of those in power.

Prominent poet and writer Ather Zia’s Resisting Disappearance: Military Occupation and Women’s Activism in Kashmir does not offer any political solution to Kashmir. It is instead a powerful documentation of the relentless struggle of Kashmiri women fighting for their husbands and sons who vanished in the air. The book revisits the turbulent 1990s, a period that cemented the grim reality of how Kashmiris came to be treated as “killable bodies.” Drawing on real experiences and collective memories, it presents a deeply human understanding of Kashmir’s suffering. This work chronicles the tireless efforts of the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP), capturing both their unyielding activism and their undeterred quest for justice.

On the other hand, Colonizing Kashmir: State-Building under Indian Occupation by Hafsa Kanjwal examines how the centrality of Kashmir in the Indian imagination was carefully manufactured through tourism, cinema, and state propaganda. It shows how the pro-India Prime Minister Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad’s vision of “development” in the post-Independence period became a curse for Kashmiris, masking dispossession and control beneath the language of progress. Armed with irrefutable evidence, the book charts the slow, deliberate transformation of Kashmir into a colony.

Renowned journalist and editor of Kashmir Times, Anuradha Bhasin, in her book A Dismantled State: The Untold Story of Kashmir After Article 370, pieces together the harrowing sequence of events and arrests that unfolded before and after August 5, 2019. She takes the reader into the heart of that suffocating period, when phone lines went dead, the internet vanished, and an entire population was cut off from the outside world -left to endure its darkest hours in enforced silence.

None of these works are fiction -and that is precisely why they are feared. Built on meticulous research, every claim is supported by official records, historical documents, and newspaper archives. In many, the bibliography is longer than the main text. A.G. Noorani’s The Kashmir Dispute – 1947–2012 is a case in point: apart from a brief preface, it is a compilation of letters, treaty documents, and meeting records that lay bare political realities. These books are not opinion pieces; they are evidence files -and that makes them impossible to dismiss.

The Zuban books published Do You Remember Kunan Poshpora? stands as a testament to the courage of women from the twin villages of Kunan and Poshpora, who survived mass rape by military personnels on the fateful night of February 23, 1991. It chronicles their decades-long battle for justice, reignited by the nationwide protests after the 2012 Nirbhaya rape case. Here, memory becomes a weapon -a shield against erasure, a refusal to forget, and a demand for accountability.

The right to read, the right to truth

Every book contains both facts and interpretations. Truth, misconception, and conclusions drawn from pain all depend on the reader’s knowledge, attitude, and perspective. The reader must decide what resonates as truth. For example, Rahul Pandita’s Our Moon Has Blood Clots movingly tells of the suffering endured by Kashmiri Pandits when they were forced to flee. These are undeniable wounds and worth knowing. Yet emotion sometimes veils other truths -such as the violence and trauma faced by Kashmiri Muslims after the Pandits’ displacement. To truly understand any region or period -books from all perspectives must be available. The determination of truth must remain with the reader.

Why this moment demands defiance

What the Indian government has done goes far beyond censorship—it is an assault on democracy itself. By banning books, it drags history into darkness and shows contempt for the wisdom and dignity of its readers. Such acts promote selective narratives that favour the government’s actions, laced with distortions, designed to inflame emotions and serve political ends. They manufacture a hollow patriotism that works like a sedative -dulling reason and numbing critical thought. The clearest example is propaganda films like The Kashmir Files. As the state parades such films, granting them tax exemptions and free screenings as if they were unquestionable truths -it tramples underfoot the books that contain verifiable history.

This is not a policy to debate -it is an outrage to resist. To believe it will stop here is to ignore history. We have already seen that when an undemocratic act takes root in one place, it soon spreads across the nation. Any writing that critically examines government actions will be targeted, just as the bans have already begun -starting with printed newspapers, extending to digital media, and even silencing YouTube screenings.

Banning books is not merely censorship; it is the demolition of history, the silencing of political thought, the erasure of public memory. And of all the weapons a state can wield against its people, this is the most insidious -for when the printed word is killed, the mind is next. Those who will not let books live will not hesitate to come for our dreams. In the struggle to keep books alive, we safeguard the very breath of our freedom.

Rama Sundari is a political commentator

14 August 2025

Source: countercurrents.org