By Samer Alatout

This commentary is based on an episode of Rethinking Palestine, Al-Shabaka’s podcast series, which aired on May 27, 2024. The discussion may be listened to in full here.

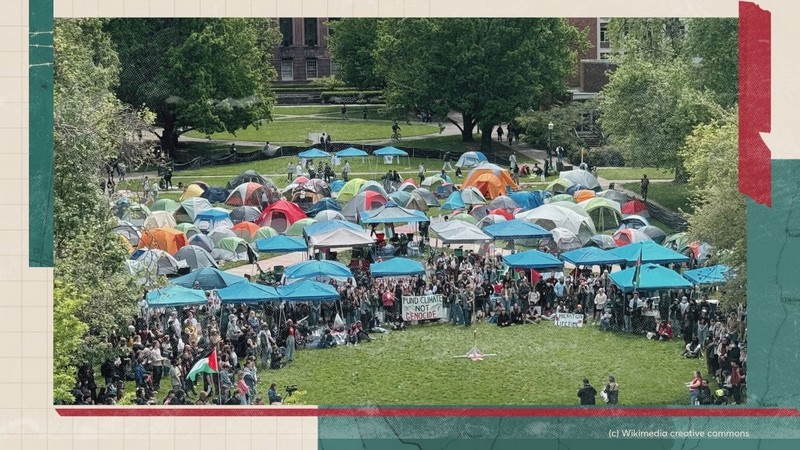

In April 2024, students at Columbia University set up an encampment on campus grounds in solidarity with the Palestinian people—particularly those in Gaza facing the ongoing genocide. Their demands to the university administration were simple: to disclose investments and divest from companies complicit in the oppression of Palestinians. Similar encampments soon spread across college and university campuses throughout the US, as well as in Canada, the UK, and Europe.

While unprecedented in the context of Palestine solidarity, these encampments and protests follow a long legacy of student mobilization in the US against war and imperialism. Just like their predecessors, students today are facing brutal repression from university administrations, as well as from security and policy forces. Hundreds of students and faculty members have been injured, arrested, and even suspended from their institutions. They have also faced smear campaigns by the media and agitators, attempting to discredit the protests and the people behind them.

This commentary offers key insights into this new wave of student mobilization. It details student demands and places them within the historical legacy of US student organizing. The commentary also examines the relationship between university administrators, students, and faculty, and finds hope in the kinship emerging between the latter two groups at this critical moment.

Student Demands: Understanding Disclosure and Divestment

The US has a long history of student activism, particularly across university campuses. Indeed, student mobilization previously emerged during the civil rights movement, Vietnam War, anti-apartheid movement, and Iraq War. Each of these efforts followed a similar trajectory: In the short term, student activists were met with condemnation from university administrators and violent police responses. Meanwhile, the impact of student actions and demands began to feed into a growing discourse of condemnation towards the US and its geopolitical allies. Years later, the very universities that attempted to stifle such mobilizations would come to celebrate their former students, acknowledge their bravery, and claim that times have since changed and campuses were now safe spaces for justice-based organizing.

Universities across the US are generating profits to sustain operations by investing millions—if not billions—of dollars in companies that actively support Israeli settler colonization and Palestinian subjugationSHARE ON X

Standing on the shoulders of these historic mobilizations, today’s student organizing efforts are centered on US complicity in Israel’s genocidal assault in Gaza. Through protests and encampments, the students are making specific demands of their universities—namely, disclosure and divestment. To effectively grasp the impact and potentiality of these mobilizations, it is important to first understand the basis behind their calls.

Many colleges and universities across the US have endowments that are intended to help fund the core operational costs of the institutions in perpetuity. The value of a university endowment varies, with Harvard University possessing the largest at a total of roughly $50 billion. The top 15 university endowments amount to over $315 billion. Importantly, these endowments are sustained through investments in stocks, capital, and other instruments. Some of these investments feed directly into companies that help to uphold the infrastructure of Israeli settler colonization—including weapons manufacturer Lockheed Martin, technology company Hewlett Packard Enterprise, and telecommunications company Motorola Solutions. Lockheed Martin, for example, has provided Israel with Hellfire missiles, transport planes, as well as F-16 and F-35 fighter jets throughout the genocide in Gaza. Hewlett Packard Enterprise has supplied the Israeli government for years with various systems that enable its ministries to surveil and store information on Palestinians throughout the West Bank and Gaza. Meanwhile, Motorola Solutions remains the sole supplier of 4G to the Israeli military and previously designed a unique smartphone model for the Israeli military.

Thus, universities across the US are generating profits to sustain their operations by investing millions—if not billions—of dollars in companies that actively support Israeli settler colonization and Palestinian subjugation. Accordingly, students are calling on their academic institutions to divest from such companies and develop investment strategies that better align with the universities’ stated values.

This demand is part of a long student history of divestment calls, which was widely prevalent throughout the anti-apartheid movement in the 1970s and 1980s. During these years, students advocated for universities to become “South Africa free” by cutting financial ties with companies who conducted business with the apartheid regime. The movement resulted in 155 colleges and universities across the US and Canada divesting from South Africa between 1977 and 1988. Furthermore, its impact spread beyond college campuses to directly impact the decision-making of US corporations, many of whom—including General Electric and PepsiCo—ultimately ceased operations in South Africa until the end of apartheid. Thus, divestment efforts have proved effective for nearly fifty years.

Demands for disclosure and divestment go hand-in-hand: Universities must make their investments open to public access, and must then divest from those actively engaged in human rights violationsSHARE ON X

The divestment demand also builds on the call made by the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) Movement, an organizing framework that is increasingly becoming part of the mainstream public discourse. The movement’s prevalence has significantly increased as a result of the presence of strong Palestinian voices in the public sphere, especially across social media platforms, in recent years. This is a major shift from past decades, where Palestinian experts and analysts were sidelined in favor of non-Palestinian advocates. Furthermore, the brutality of the genocide in Gaza has pushed the boundaries of risktaking for many: What may have felt like too great a risk in the past—either on our careers, reputations, or safety—now feels necessary in the face of Palestinian erasure. This is despite the many local, state-wide, and nation-wide crackdowns on BDS activity, including legislation across 38 states to penalize those participating in boycotts. Today, we are witnessing Palestinians and Palestinian Americans at the helm of these organizing efforts and risk-taking, and students are carrying this critical work forward.

Still, a major obstacle remains for this call to be effective: the majority of college and university investments remain private. That is, academic institutions largely refuse to publicly disclose their investment portfolios; many establish distinct foundations to house profits and manage investments, so as to further distance the university from its financial liabilities. As such, students and faculty are unable to make concrete demands for divestment. This is why the call for disclosure is central to the current student uprising. Financial transparency is a basic democratic principle that all higher education institutions—particularly public universities—should adhere to.

Student demands for disclosure and divestment therefore go hand-in-hand: Universities must first make their investments open to public access, and must then divest from those companies actively engaged in fundamental human rights violations.

Student Encampments: Spaces of Resistance & Future-Building

The student encampments lay bare a number of truths about university administrations. Firstly, that they perceive themselves as the sole arbiters of these institutions, separate from faculty, staff, and student body. Such is made abundantly clear when protest spaces are unilaterally declared illegal and police forces are called in for their dismantlement. In deploying the threat—or at times, actual use—of violence, university administrations exemplify their power as diametrically opposed to that of the students. Indeed, doing so fortifies a relationship between the two that is built on the demand for compliance, and on punishment in the face of defiance.

Students are reacting to the exceptional horror with an exceptional response—both by demanding accountability from their institutions as well as by prefiguring what an alternative and just world could look likeSHARE ON X

Despite this, we must recall that the administration is not synonymous with the university itself. Rather, the university is made up of a constellation of groups—including students, faculty, and staff. Each of these constituencies has a stake in the institution, and each should accordingly participate and have representation in its governance. This is exactly what the students are demanding: A direct role in determining how investment decisions are made, and which values or ethics are used to inform those decisions. The students deserve to feel a mutual sense of belonging and kinship with the university—that they belong to it, and that it belongs to them. The same is true for all constituencies on university and college campuses, and participating in institutional decision-making is a key part of this process.

The student encampments have also revealed the contrasting responses on campuses to the Palestinian genocide in Gaza. While many university administrations desire to continue business as usual and disregard their complicity, students are reacting to the exceptional horror with an exceptional response—both by demanding accountability from their institutions as well as by prefiguring what an alternative and just world could look like. From the outside, the tent-filled encampments serve as a physical and symbolic reminder of the refugee camps that have emerged in Gaza since October 2023. Within these encampments, however, students are building forward-looking spaces that are inclusive, participatory, and safe for all. Like their predecessors, these spaces are filled with skills-sharing and popular education resources, rooted in an ethos of community-building and liberation. In this way, they are pushing the boundaries of what is considered possible on university campuses.

The recent student mobilizations have also galvanized university faculty and staff, and strengthened the coalition between these constituencies, in what may be a lasting impact beyond the current negotiations. From the faculty side, many are keen to support the students through assisting with negotiation processes, passing down historical expertise, and offering physical protection (as may be seen through the numerous human chains formed by faculty around student protestors). It is in these times that we are reminded that the role of the professor is more than just pedagogical and educational; it is also about providing a nurturing and protective environment for students to thrive intellectually, emotionally—and sometimes, unfortunately, that requires standing between them and a violent police force. In these moments and in these spaces, the power relationship between students and faculty shifts; we offer what we can and only when it is solicited, deferring to the organizers for guidance. Above all, as faculty we remain inspired and indebted to these students, who are carrying on the long legacy of change-making towards justice.

Al-Shabaka Policy Member Samer Alatout is an associate professor in the Department of Community and Environmental Sociology and the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies at…

14 July, 2024

Source: al-shabaka.org