By Dr Ramzy Baroud

Some promises are made and kept; others disavowed. But the ‘promise’ made by Arthur James Balfour in what became known as the ‘Balfour Declaration’ to the leaders of the Zionist Jewish community in Britain one hundred years ago, was only honored in part: it established a state for the Jews and attempted to destroy the Palestinian nation.

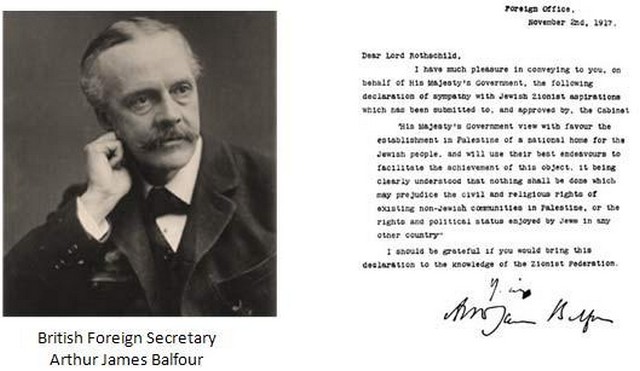

In fact, Balfour, the foreign Secretary of Britain at the time his declaration of 84 words was pronounced on November 2, 1917, was, like many of his peers, anti-Semitic. He cared little about the fate of Jewish communities. His commitment to establishing a Jewish state in a land that was already populated by a thriving and historically-rooted nation was only meant to enlist the support of wealthy Zionist leaders in Britain’s massive military buildup during World War I.

Whether Balfour knew it or not, the extent to which his short statement to the leader of the Jewish community in Britain, Walter Rothschild, would uproot a whole nation from their ancestral homes and continue to devastate several generations of Palestinians decades later, is moot. In fact, judging by the strong support his descendants continue to exhibit towards Israel, one would guess that he, too, would have been ‘proud’ of Israel, oblivious to the tragic fate of the Palestinians.

This is what he penned down a century ago:

“His Majesty’s government views with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country. I should be grateful if you would bring this declaration to the knowledge of the Zionist Federation.”

Speaking recently at New York University, Palestinian professor Rashid Khalidi described the British commitment, then, as an event that “marked the beginning of a century-long colonial war in Palestine, supported by an array of outside powers which continues to this day.”

But oftentimes, generalized, academic language and refined political analysis, even if accurate, masks the true extent of tragedies as expressed in the lives of ordinary people.

As Balfour finished writing down his infamous words, he must have been consumed with how effective his political tactic would be in enlisting Zionists to join Britain’s military adventures, in exchange for a piece of land that was still under the control of the Ottoman Empire.

Yet, he clearly had no genuine regard for the millions of Palestinian Arabs – Muslims and Christians alike – who were to suffer the cruelty of war, ethnic cleansing, racism and humiliation over the course of a century.

The Balfour Declaration was equivalent to a decree calling for the annihilation of the Palestinian people. Not one Palestinian, anywhere, remained completely immune from the harm invited by Balfour and his government.

Tamam Nassar, now 75 years old, was one of millions of Palestinians whose life Balfour scarred forever. She was uprooted from her village of Joulis in southern Palestine, in 1948. She was only five.

Tamam, now lives with her children and grandchildren in the Nuseirat Refugee Camp in Gaza. Ailing under the weight of harsh years, and weary by a never-ending episode of war, siege and poverty, she holds on to a few hazy memories of a past that can never be redeemed.

Little does she know that a man by the name of Arthur James Balfour had sealed the fate of the Nassar family for many generations, condemning them to a life of perpetual desolation.

I spoke to Tamam, also known as Umm Marwan (mother of Marwan), as part of an attempt to document the Palestinian past through the personal memories of ordinary people.

By the time she was born, the British had already colonized Palestine for decades, starting only months after Balfour signed his declaration.

The few memories peeking through the naïveté of her innocence were largely about racing after British military convoys, pleading for candy.

Back then, Tamam did not encounter Jews or, perhaps, she did. But since many Palestinian Jews looked just like Palestinian Arabs, she could not tell the difference or even care to make the distinction. People were just people. Jews were their neighbors in Joulis, and that was all that mattered.

Although the Palestinian Jews lived behind walls, fences and trenches, for a while they walked freely among the fellahin (peasants), shopped in their markets and sought their help, for only the fellahin knew how to speak the language of the land and decode the signs of the seasons.

Tamam’s house was made of hardened mud, and had a small front yard, where the little girl and her brothers were often confined when the military convoys roamed their village. Soon, this would happen more and more frequently and the candy that once sweetened the lives of the children, was no longer offered.

Then, there was the war that changed everything. That was in 1948. The battle around Joulis crept up all too quickly and showed little mercy. Some of the fellahin, who ventured out beyond the borders of the village, were never seen again.

The battle of Joulis was short-lived. Poor peasants with kitchen knives and a few old rifles were no match for advanced armies. British soldiers pulled out from the outskirts of Joulis to allow Zionist militias to stage their attack, and the villagers were chased out after a brief but bloody battle.

Tamam, her brothers and parents were chased out of Joulis, as well, never to see their beloved village again. They moved about in refugee camps around Gaza, before settling permanently in Nuseirat. Their tent was eventually replaced by a mud house.

In Gaza, Tamam experienced many wars, bombing campaigns, sieges and every warfare tactic Israel could possibly muster. Her resolve is only weakened by the frailty of her aging body, and the entrenched sadness over the untimely deaths of her brother, Salim, and her young son, Kamal.

Salim was killed by the Israeli army as he attempted to escape Gaza following the war and brief Israeli invasion of the Strip in 1956, and Kamal died as a result of health complications resulting from torture in Israeli prisons.

If Balfour was keen to ensure “nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine,” why is it, then, that the British government remains committed to Israel after all of these years?

Isn’t a century since that declaration was made, 70 years of Palestinian exile, 50 years of Israeli military occupation all sufficient proof that Israel has no respect for international law and Palestinian human, civil and religious rights?

As she grew older, Tamam began returning to Joulis in her mind, more often seeking a fleetingly happy memory, and a moment of solace. Life under siege in Gaza is too hard, especially for old people like her, struggling with multiple ailments and broken hearts.

The attitude of the current British government, which is gearing up for a massive celebration to commemorate the centennial of the Balfour Declaration suggests that nothing has changed and that no lessons were ever learned in the 100 years since Balfour made his ominous promise to establish a Jewish state at the expense of Palestinians.

But this also rings true for the Palestinian people. Their commitment to fight for freedom, also remains unchanged and, neither Balfour nor all of Britain’s foreign secretaries since then, have managed to break the will of the Palestinian nation.

That, too, is worth pondering upon.

– Ramzy Baroud is a journalist, author and editor of Palestine Chronicle. His forthcoming book is ‘The Last Earth: A Palestinian Story’ (Pluto Press, London). Baroud has a Ph.D. in Palestine Studies from the University of Exeter and is a Non-Resident Scholar at Orfalea Center for Global and International Studies, University of California Santa Barbara. His website is www.ramzybaroud.net.