By Vijay Prashad

On June 22, France’s outspoken ambassador to the United States, Gérard Araud, said: “The next President will face a multipolar world where the U.S. will be the main but not the only power. Realism is the only possible agenda.” It is unusual for such a close ally of the U.S. to make this statement. After all, it has been one of the pillars of the U.S.’ self-identification that it is the major force in the world. Political leaders in the U.S. routinely speak of the country as the greatest in the world, the only country with truly global ambitions and with global reach. U.S. military bases litter the continents of the world, and U.S. warships move from ocean to ocean, bearing terrifying arsenals. When the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) collapsed in 1991, it became self-evident that the U.S. was the sole remaining superpower. Unipolarity defined the world order. So what is it that makes the French ambassador speak of a multipolar world?

Araud is not alone in his realism. Some years ago, former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger alerted the political elite against its belligerent rhetoric about China. In his 2011 book On China, Kissinger wrote of the need for the U.S. and China to form a partnership which would be “essential to global stability and peace”. Confrontations over the shipping lanes in the South China Sea and disputes over currency manipulation dangerously flirt with the language of war. “Relations between China and the United States need not—and should not —become a zero-sum game,” wrote Kissinger. China had become too important for the U.S. to indulge in Cold War theatrics. It was far more important, Kissinger noted, for the two powers to come to an understanding on how to confront global imbalances—whether economic or political.

The Republican nominee for President, Donald Trump, not known for his political sobriety, is running on a campaign slogan that admits to today’s reality. “Make America Great Again!” says the slogan, which acknowledges the weaknesses of the U.S. at this present time. At least Trump admits to this, although he hastily suggests that somehow his presidency, miraculously, will transform the vulnerabilities of the U.S. into strengths. Trump blames the presidency of Barack Obama for the collapse of the country’s strength. He condenses the right-wing antipathy to Obama in his belief that it is Obama who has brought the U.S. into disrepute. Racism feeds into this rhetoric, but so does masculinity. Obama is too dark and too feminine to keep the U.S. great. It requires the machismo of Trump to do the job. What Trump does not see, but what Araud and Kissinger recognise, is that the current weakness of the U.S. is not somehow because of the policies of Obama.

Trump would like to channel Ronald Reagan, who said during his presidency in the 1980s: “Let’s reject the nonsense that America is doomed to decline, the world is sliding toward disaster no matter what we do.” But Reagan came to power in a different era. Then the USSR had been deeply weakened by economic crises, China had not yet emerged as a serious economic powerhouse and few other “rivals” threatened American supremacy. Reagan could afford to junk the “false prophets of decline”. The U.S. could take advantage of its financial power to reshape world affairs in its image. But times have changed. No longer does the U.S. have the economic and political power to thrust its “tremendous heritage of idealism” (as Reagan put it in 1981) onto the world. It is not the U.S. culture and character that produced its supremacy in the 1980s. It is not enough, as Trump does, to lean on culture and character for another thrust towards world leadership.

Reagan could pillory President Jimmy Carter, a soft-spoken Democrat, for the weakness of the U.S. Machismo came easily to Reagan. He had played enough cowboys in the movies. Obama is not Carter. He has been President for eight years, during which he has found that U.S. power has been depleted. What has led to this “decline of America”?

First, the great social process of globalisation allowed U.S. firms to move their production sites around the world. The “global commodity chain” provided benefits to the owners of ideas and capital. This “1 per cent”, as the Occupy movement called them, was able to earn ferocious returns on investment, while the workers of the U.S. found themselves unemployed, underemployed and certainly underpaid. Income inequality increased and access to basic social goods declined for the bulk of society. Bank credit allowed the workers to take enormous loans so as to manufacture a life along the grain of the American Dream. What these workers received was not “credit” but “debt”—debt rates on home mortgages, credit card, and college tuition rose astronomically. The bursting of the home mortgage balloon in 2007 set off the global credit crisis, which is one of the great indicators of the fragility of U.S. power.

Second, at the same time as the U.S. struggled with its financial crisis and its military overextensions in Afghanistan and Iraq, the Western alliance system frayed. The most important emergence, under the shadow of the Western alliance system, was the rapid growth of the German economy, which essentially absorbed major gains from European unity. German banks dominated the continent, as German firms took advantage of labour costs and its technological advancement to make the most of the common market. Southern Europe, from Portugal to Greece, suffered from the German success. European unity was threatened by this disparity.

At the same time, France made a dash to reclaim its central role amongst its old colonies, particularly in Africa. French military intervention in West Africa came alongside attempts to undermine the growth of a new African currency, the Afric. It was Araud, after all, who persuaded U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton to pursue the war against Libya in 2011. Meanwhile, the United Kingdom wheezed itself into isolation from the European Union, as the Conservatives became churlish about the utility of Brussels. Brexit indicates the end of “European unity” as a dream, a major partner of the U.S. The old Western alliance system—the G7 and NATO—might well become collateral damage in this debate around “Europe” and in the rise of the old European imperial powers towards illusions of greatness.

Third, as Europe implodes, China’s rise seems secured by a crafty new relationship with a defensive Russia. The attempt by the West to encage both Russia and China seems to have failed. Europe’s gambit in Ukraine will fall apart as its own energy needs imperil a reconsideration of the sanctions against Russia. Meanwhile, on the eastern flank, China’s economic dominance has broken into the Western alliance system, with countries from Japan to Australia eager for trade with China rather than to remain as ramparts for a Western military project. Economic and military arrangements between Russia and China seem to increase as each month goes by. The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation’s (SCO) expansion into becoming a major Asian bloc, now including India and Pakistan, is an indicator of regionalism that has kept the West out. The Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), created in 2010, pioneered this approach, since it actively saw itself as an alternative to the Organisation of American States, which was a U.S.-driven regional body. Both the SCO and CELAC have kept the U.S. and its major allies outside their decision-making process. It is a sign of the emergence of global multipolarity.

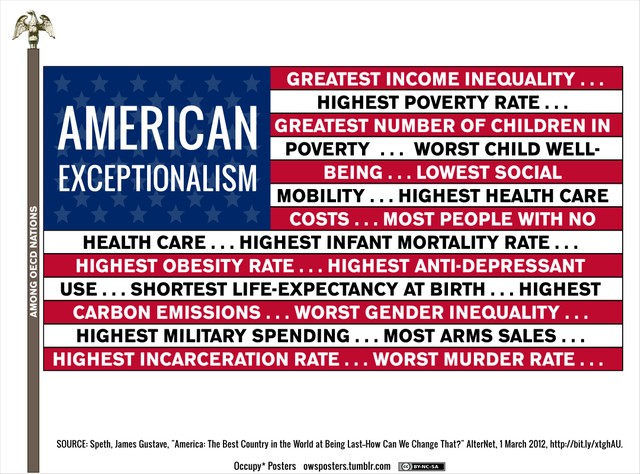

Raised on a diet of “American exceptionalism”, the U.S. public was unprepared for the compromises essential to Obama’s presidency. The deal with Iran and the inability to pursue regime change in Syria are two graphic indications of Obama’s sobriety. The Russian intervention in Syria, the first major one since the Soviet entry into Afghanistan and the Cuban entry into Angola, demonstrated the limitations of U.S. power. In February, two aid workers corralled U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry at a meeting in Istanbul. They wanted to know why the U.S. had not been more robust against the government of Bashar al-Assad. Kerry, irritated, replied: “What do you want me to do? Go to war with Russia?” These are important questions, a measure of the reality faced by the Obama team. A frazzled West and a defensive Russia-China alliance provide a new balance to the world order. The days of cowboy diplomacy are long gone. That is what Gérard Araud implies with his message.

This essay originally appeared in Frontline (India).

8 July 2016