By Franklin Lamb

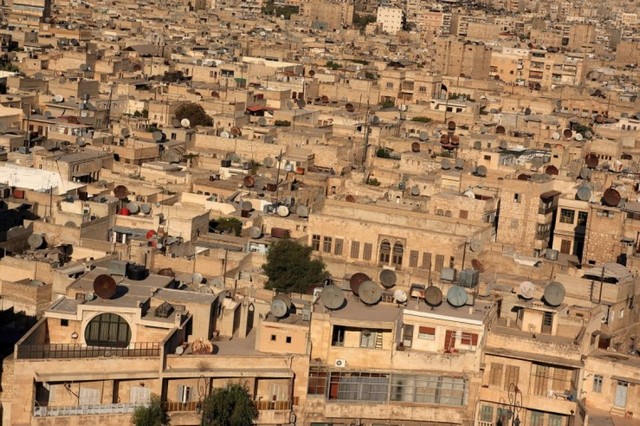

With the Syrian army deep inside Aleppo’s old city: This observer has long sought an extended visit to the old city of Aleppo which is also one of this cradle of civilizations cultural and educational centers. Despite being in a continuing war zone, the visit materialized when security authorities granted permission and assistance to this observer to complete research finalizing more than two years of research across Syria on the subject of Syria’s Endangered Heritage: The Story Of A Nations Fight To Preserve Its Cultural Heritage.

Several visits to damaged archeological sites and quality briefings soon turned a few days into more than a week with more than a two dozen detailed evaluations and analyses during meetings with Syrian nationalists among them, M.B. Shabani, Director of the Aleppo National Museum. Another was with Professor of Islamic Science, Bouthania Chalkhi and a group of her faculty colleagues and researchers at Aleppo’s 80,000 plus student university. Aleppo University, like nearly all of Syria’s institutions of higher learning has paid a bitter price for keeping its classrooms open. On January 15 2013 the School of Architecture was shelled and more than 90 students and visitors on campus were killed. By shocking coincidence, Damascus University’s School of Architecture was similarly shelled only five weeks later on March 28, 2013, killing more than 15 students.

Two military commanders, currently with their troops deep inside the old city near the ancient Citadel, seemed more like college philosophy instructors than military men, as they discussed the massive destruction inside the old city including more than 1,600 khans and souks.

This observer and another American, a special young man from Maryland who is studying Arabic in this region, was guided along with two colleagues on a long nighttime tour and briefing among alleys inside the ancient burned out and blasted medina souk. Sometimes as we paused our army guide would comment on how parts of the souk might be salvageable and how he felt anger at what was wantonly inflicted in the area now under his command. Our military escort advised us that our tour of the remains of this UNESCO World Heritage site was the first such visit allowed since its destruction more than 18 months ago. He even joked that nearly a month ago a team with the BBC was offered a more limited tour but that a famous female BBC Middle East correspondent, one of this observers favorites, turned back after penetrating the warrens by less than 50 yards.

Surely not the first or last time that Yankees have followed up Brits to complete a task, our interpreter from Damascus giggled.

For hours we trudged through the widely reported massive destruction observing the burned detritus of what were formerly historic “khans” which for centuries traded and sold specialty items as noted below. The tour left one in numbed disbelief over the extent of the destruction.

Among the most historic souks in Aleppo’s old city, verified by this observer as having been destroyed on 9/29/2012, all within the burned out covered alleyways of Souk al-Madina, include, but are not limited to the following. This partial list is presented as a condolence to Syrian artisans and citizens whose lives have been deeply, negatively, and irreversibly damaged. Wanton destruction of a significant part of the shared global heritage of us all.

Khan al-Qadi, one of the oldest khans (specialized souk areas) in Aleppo dating back to 1450;

Khan al-Burghul (Bulger), built in 1472 and the location of the British general consulate of Aleppo until the beginning of the 20th century;

Souk al-Saboun (soap khan) built in the beginning of the 16th century was the main center of the soap production in Aleppo;

Souk Khan al-Nahhaseen (coppersmiths), built in 1539. The general consulate of Belgium was at this location during the16th century. Before its destruction it including more than 80 traditional and modern shoe-trading and production shops;

Khan al-Shouneh, built in 1546 was a market for trades and traditional handicrafts of Aleppine art;

Souq Khan al-Jumrok or the customs’ khan, was a textile trading center with more than 50 stores. Built in 1574, Khan Al-Gumrok was considered to be the largest khan in ancient Aleppo;

Souk Khan al-Wazir, built in 1682, was the main souk for cotton products in Aleppo;

Souk al-Farrayin was the fur market, is the main entrance to the souk from the south. The souk is home to 77 stores mainly specialized in furry products;

Souk al-Hiraj, traditionally was historically the main market for firewood and charcoal. Until its destruction it reportedly included 33 stores mainly dealing in rug and carpet weaving and products;

Souk al-Dira’, was perhaps the main center for tailoring and one of the most organized alleys in the souk with more than 60 workshops;

Souk al-Attareen for more than a century was the vast herbal market and in fact was the main spice-selling market of Aleppo. Before its destruction it was a textile-selling center with more than 80 stores, including spice-selling shops;

Souk az-Zirb, was the main entrance to the souq from the east and the place where coins were being struck during the Mamluk (18th century) period. All of its 72 shops featured textiles and the basic needs of the Bedouins;

Souk al-Behramiyeh, located near the Behramiyeh mosque had more than 20 stores trading in foodstuffs;

Souk Marcopoli (derived from Marco Polo), was a center of textile trading with 29 stores.

Souk al-Atiq specialized in raw leather trading with 48 outlets;

Souk as-Siyyagh or the jewelry market was the main center of jewelry shops in Aleppo and Syria with more than 100 outlets located in 2 parallel alleys.

The Venetians’ Khan, was home to the consul of Venice and the Venetian merchants.

Souk an-Niswan or the women’s market, was an area where accessories, clothes and wedding equipment’s of the bride could be found;

Souk Arslan Dada, is one of the main entrances to the walled city from the north. With 33 stores, the souk is a center of leather and textile trading;

Souk al-Haddadin, is one of the northern entrances to the old city. Located outside the main gate it was considered to be the old traditional blacksmiths’ market with more than 40 workshops;

Souk Khan al-Harir (the silk khan) was another entrance to the old city from the north and was buiit in the second half of the 16th century. The silk souk hosted the Iranian consulate until 1919.

Suweiqa (small souk) consisted of 2 long alleys: Sweiqat Ali and Suweiqat Hatem, located in al-Farafira district which contained markets mainly specialized in home and kitchen equipment.

One is left distraught over the seeming futility of even contemplating rebuilding this world heritage site. Would it require half a century to reconstruct, as was required in Dresden Germany following three days of firebombing by British and American planes, which began on February 13, 1945?

There are many questions to be answered whether rebuilding would ever authentically restore Aleppo’s old city to what it had been for centuries.

Would “restoration” render it a sterile or glitzy place with the main focus on the tourist dollar? Which countries would help rebuild it and where would the money come from, and could Syria and her experts influence and oversee the reconstruction? One professor of Archeology at Aleppo University asked, “Could a rebuilt Medina souk ever again be ‘my neighborhood, the cherished neighborhood of my youth and of my family over preceding generations?” Many of the individual souks, maybe 12 feet by 10 feet were valued at close of one million dollars and restoration would cost hundreds of millions.

Locating experts in areas amidst fairly intense government security concerns and measures which are much greater than in Damascus was not always easy. It was compounded by the fact of 2 hour per day electricity and water shortages, yet one still had the opportunity to discuss and learn from a cross section of this community including academic, governmental, business and citizen activists.

Three tentative conclusions arrived at by this observer from fascinating and heart felt discussions include one from Professor Lamis Herbly, Chairperson of the Archeology department of Aleppo University. This warm and elegant lady’s eyes welled with tears, being the mother of two youngsters and who worries daily about the safety of her children while insisting that they stay in school despite the dangers, described her and her communities losses. She also expressed the concerns of her academic colleagues that if and when reconstruction begins in the old city of Aleppo that it must be done with utmost care and under Syrian experts control. She explained what she meant was that reconstruction in Syria not mirror what was done in Beirut to renovate the ‘downtown’ area which separated Muslim and Christian militia along the ‘green line’ during Lebanon’s 15 year (1975-1990).

One professor declared the reconstruction of downtown Beirut and the filling in of Beirut harbor with thousands of years of antiquities as Saudi financed, behemoth Mercedes Benz earth movers shoved much of Lebanon’s history into the sea to make way for upscale fancy tourist attracting shops catering to rich Gulf tourists (of whom there are very few these days). “So they can buy yet more jewelry and Paris fashions?” she asked. Someone else joined in saying what happened in Lebanon was a cultural crime.

“Downtown Beirut is an obscenity,” one PhD candidate, a young lady who formerly lived near the old city insisted. This student is among those who joined efforts that began nearly two decades ago to preserve and protect one of Aleppo’s two remaining synagogues in the Samoua neighborhood. She vowed that citizens of Aleppo must not and will not allow what happened in Beirut to happen here in Aleppo.

Another concern, discussed with citizens in Aleppo is the often expressed worry over whether other countries that unfortunately had, sometimes directly and sometimes indirectly, a hand in the destruction of much of Syria cultural heritage would be willing to help with its preservation and reconstruction. This observer, who has studied the subject over the past two years in Syria shared this concern, but sought to assure Aleppo interlocutors that indeed many governments acknowledge with gratitude the work of the Syrian people in protecting our mutual global heritage, in the custody of country’s people for millennia, share their horror over what has happened and indeed want to help as soon as a lasting ceasefire can be achieved. This subject was one of the most frequently raised by both experts and average citizens in Aleppo.

Archeological and restoration experts in Syria tend to agree with international research findings that estimate that despite the vast heartbreaking destruction, looting, politically motivated desecration of countless mosques and churches as well as thousands of years of pagan artifacts, that approximately 96 percent of our shared cultural heritage in Syria can be repaired, restored, or even replicated when no other option in available. What is urgently needed before more damage is infected is a ceasefire or freeze in place and is being discussed by UN mediators. Objects that have been blow up in a frenzy of ignorance and malevolence are lost and irreplaceable. The tens of thousands of illegally excavated and looted priceless antiquities now scattered to private collections and speculators have been routed through, Lebanon, Turkey, Israel, Iraq and Jordan. They must be returned as part of a massive international antiquities retrieval campaign that should include an expanded role for Interpol, auction houses and governments as well as international institution of the UN. One student at Damascus University told this observer recently that she and fellow students have started an international campaign focusing on auction houses and governments seeking the return of stolen Syrian antiquities. They have named their student led organization: “I’m Syrian and I need to go home. Please help me.”

One of life’s seeming wonderful incongruities is experienced by visitors all across Syria these days. It has to do with the human spirit. Examining and contemplating just the one example of damage to our shared global heritage in Aleppo, as depressing and discouraging as any of the damage done to our shared global culture heritage one might be excused for becoming cynical and even somewhat catatonic as one observes and studies the desecration and destruction here in Aleppo and in so many other areas.

But not the Syrian people. Rather than slump and becoming crestfallen, this observer finds Syrians resolute and even somehow inspiring in their determination to preserve, protect and restore our cultural heritage. Space allows for one example.

This observer, spent an afternoon this week next to the glowing fireplace on a cold rainy day in the warm and cozy office of Mohammad Kujjah, Director of the 1924 founded Archeological Institute of Aleppo. I was joined by some of his staff, all experts on preserving archeological treasures. One taciturn scholar sitting next to me, who I thought appeared to be on the verge of nodding off, saddening perked up and squeezed my arm to get my undivided attention. He then proceeded to further light up the bookcase lined office by presenting a brilliant lecture that, were he asked, this observer would entitle something like:

The Germans rebuilt Dresden and the Syrians will rebuild Aleppo!

He began with fascinating comparisons between what was and what was done to Dresden beginning on February 13, 1945 and what happened to Aleppo’s old city on September 28, 2012. Dresden was carpet bombed by 722 RAF and 527 USAAF bombers that dropped 2431 tons of high explosive bombs, and 1475.9 tons of incendiaries. The high explosive bombs damaged buildings and exposed their ancient wooden structures, while the incendiaries ignited them. The massive wooden structures, like in Aleppo, burned to the ground. The resultant firestorms killed an estimated 50,000 to 200,000 people, although the total number is disputed. Dresden, an historic center held no strategic value. The war in Europe was coming to an end, and the city was packed with refugees fleeing the advancing Red Army. It is widely believed that the bombing was a revenge attack for the German bombing of Coventry as well as a show of force.

As he spoke the professor displayed for his guests a large photograph of Dresden taken in early March of 1945. The high explosive bombs damaged buildings and exposed their wooden structures, while the incendiaries ignited them. The massive wooden structures of Aleppo’s old city also burned to the ground.

The archeologist lectured his rapt American audience, seemingly also to the delight of his Aleppine colleagues on how Aleppo reconstruction could be achieved and he spoke of the Syrian peoples will that it shall be done.

All people of good will who accept their personal duty to join the people of Syria in preserving, protecting and restoring our shared global heritage can take solace from what this observer witnessed an exhilarating demonstration of the sublime capacities of our shared human spirit as we help to salvage our cultural heritage.

Franklin Lamb’s most recent book, Syria’s Endangered Heritage, An international Responsibility to Protect and Preserve is in production by Orontes River Publishing, Hama, Syrian Arab Republic.

20 December, 2014

Countercurrents.org