By Hamid Dabashi

If Hollywood wants to turn to Rumi, may Rumi’s blessings be on Hollywood.

Imagine Leonardo DiCaprio, say as Jordan Belfort in Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street (2013). Now imagine him as Rumi. Yes, Rumi: the Muslim mystic poet of the 13th century.

Now imagine Robert Downey Jr, say as Tony Stark/Iron Man in Jon Favreau’s Iron Man (2008). Now imagine him as Shams-e Tabrizi. That’s right: the mysterious mystic centre of Rumi’s deepest and most moving affections, the very inspiration behind his monumental collection of lyrical poetry.

Believe it or not, this is not a mere flight of fantasy but the combined intention of a major Hollywood scriptwriter and a producer who have evidently come together to make a biopic on the Muslim mystic, scholar, thinker, and poet Mawlana Jalal al-Din Rumi: the author of two monumental masterpieces of Persian poetry, the Mathnavi and the Divan-e Shams-e Tabrizi, the founder of the Mevlevi Order, whose Mausoleum in Konya is the pilgrimage destination of millions of his devotees from around the globe.

“An Oscar-winning screenwriter,” we read in the news, “has agreed to work on a biopic about the 13th-century poet Jalaluddin al-Rumi. David Franzoni, who wrote the script for the 2000 blockbuster Gladiator, and Stephen Joel Brown, a producer on the Rumi film, said they wanted to challenge the stereotypical portrayal of Muslim characters in western cinema by charting the life of the great Sufi scholar.”

From Muslim mystic to New Age guru

Why not, was my first reaction to the news. Rumi is so big, so magnificent, so majestic a river that anyone can come closer and fill a bucketful with his grace and go about his business.

Rumi is, of course, no stranger to New Age mysticism and has been quite successfully made available in English by such cavalier “translators” as Coleman Barks and Deepak Chopra.

Though quite distant from their original Persians, these English translations indeed read very well, create an engaging emotive universe, and successfully draw global attention to a poet otherwise entirely alien to them.

When there is no rose, to borrow a metaphor from Rumi himself, what choices do people have but to remember it from a drop of rosewater!

If you read the original Persian or are otherwise familiar with Rumi through the scholarship of the hard-working but quiet Orientalists such as R A Nicholson and A J Arberry, you may roll your eyes at some of these translations.

But given Rumi’s own predilection towards a playful soul he might have smilingly approved of his poetry being taken for a ride into English with such lovely disloyalty.

You cannot really be stubbornly dogmatic about the persona and the poetry of a man who danced with words as he took all dogmas for a lovely bathing under a cascade of forgiving love. Can you?

Imagining Rumi

Be that as it may, the new biopic this report promises is going to venture into a whole different domain: how to imagine and visualise Rumi, the world he lived, the divinity he experienced, the focal points of his love and affection, the universe that he thought engulfed his life and afterlife?

Muslims who know and love Rumi, especially those who are born and raised in his original Persian poetry, will and could never be satisfied with any rendition of him – Hollywood or otherwise.

The reason for that is very simple. They have been imagining him in their own mind for generations and lifetimes, and the slightest variation from that imagining will lead them the wrong way.

The incurable banality of Hollywood for casting famous actors of European descent in leading roles of non-European characters did not of course begin with the idea of having Leonardo DiCaprio play Rumi or Robert Downey Jr Shams-e Tabrizi.

Just take a look at a picture of a blackface Laurence Olivier as Othello or Mahdi of Khartoum, or even more recently of Christian Bale as Moses in Ridley Scott’s Exodus!

The challenge that Hollywood and its scriptwriters and producers face, however, is much more serious than who will portray Rumi.

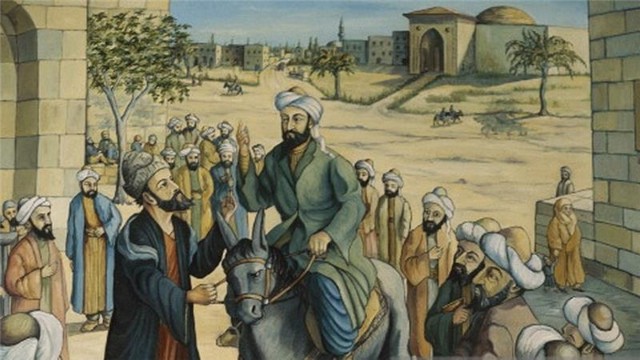

As a titanic figure in Muslim moral and intellectual history, Rumi was the product of a moment when the Mongol invasion was bringing the Abbasid and Seljuqid empires to a crushing end to build an even more enormous and opulent empire on their ruins.

Rumi was the single most towering moral intellect at the crosscurrent of that world-historic moment. His universe of imagination, the God he praised, the heavens he fathomed, the Persian poetry he perfected to the pitch of that divine presence are all at fundamental odds with the fragmentary attention span of a world in which Hollywood has turned its attention to Rumi.

As a poet, a mystic, and a prophetic soul, Rumi does not belong to anyone, and anyone can enter his presence and hope to receive the gift of his grace.

If Hollywood wants to turn to Rumi, may Rumi’s blessings be on Hollywood. But before Leonardo DiCaprio of Hollywood or Salman Khan of Bollywood is invited to play Rumi, the scriptwriter and producer are well advised quietly to whisper this piece of a ghazal that I as a mere pilgrim to Rumi’s grace translate for them from the original. I promise it will do them good:

Oh Muslims what am I to do

For I no longer know myself?

I am neither a Christian nor a Jew,

Neither a Zoroastrian, nor indeed a Muslim!

I am neither from the East nor from the West,

Neither from the sea nor from the land …

Neither from the dust nor from the wind,

Neither from water nor from fire …

Neither from this nor from the world to come,

Neither from Paradise nor from Hell,

Neither from Adam nor from Eve,

Nor indeed from the Garden of Eden –

I dwell in Noplace, my sign is Signless.

I have neither a soul nor a body,

For I come from the very Soul of all souls.

Hamid Dabashi is Hagop Kevorkian Professor of Iranian Studies and Comparative Literature at Columbia University in New York