By Hyab Yohannes

On October 3, 2013, a devastating tragedy off the coast of Lampedusa resulted in the loss of over 365 lives. Among those who drowned was my dear childhood friend, Alex, whose final text message to me reads: “Born rightless, die rightless”. These were the last words I received from him before he tragically perished without a trace. Alongside Alex was Yohanna, who passed away with her new-born baby still attached to her by the umbilical cord. In the last ten years, I have lost dozens of close relatives, childhood friends, and former colleagues. The homes of the drowned still quiet and empty, filled with the shrieks of their grieving loved ones. This sense of stillness and emptiness, alongside the haunting pain of the bereaved, continue to devour my conscience. It feels as though I am stuck in a limbo between night and day, as if I am still dreaming. Despite the sun rising, the darkness of the night still lingers.

Since 2014, the IOM Missing Migrants Project has reported that more than 56,216 forced migrants have disappeared in perilous journeys, including crossing violent borders, lifeless deserts, treacherous waters, and impoverished refugee camps. More than 23,437 bodies have not been recovered at all. Before the latest tragic incident along the Mediterranean coast of Greece, just this year alone, over 2,091 forced migrants have lost their lives. Now we have more people to add to that tally. The Guardian reports that hundreds of migrants, including 100 children, are believed to have died in this latest incident. Only 78 deaths have been confirmed according to reports, and it remains uncertain whether the remaining bodies will ever be recovered. All of these numbers represent human beings who have suffered torturous deaths. These bodies once contained lives, before they were “discounted” in “unimaginable worlds and uninhabitable places”. They once had hopes for a better life, but their yearning for freedom ended tragically.

I want to remind the reader a few things about these human calamities.

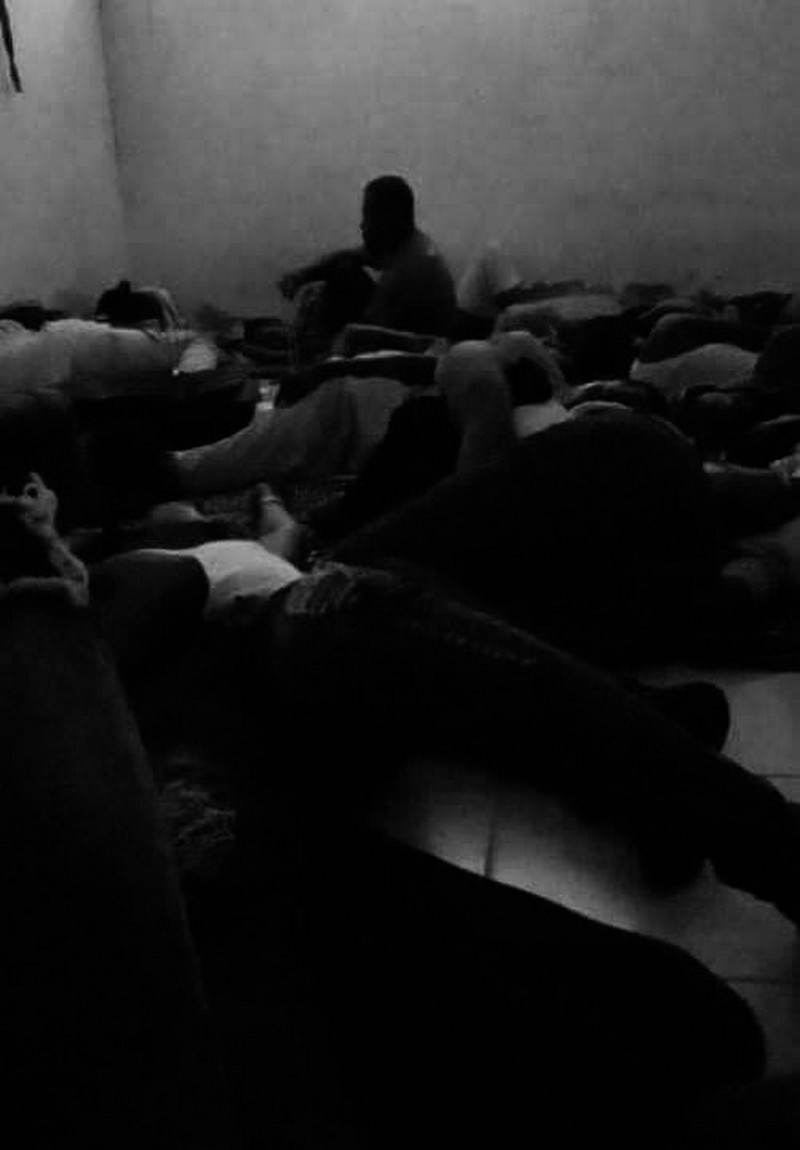

First, we must grasp the severity of the situation. The conditions faced by forced migrants in the Mediterranean Sea and elsewhere are no different from those experienced by slaves during the transatlantic slave trade between the 16th and 19th centuries. Evoking the slave condition is not just a symbolic reference to enslaved people in the past, but rather a reminder that refugees are currently experiencing similar conditions before our very eyes. We must come to terms with the fact that the dehumanisation of these racialised bodies remains endlessly normalised. It only takes a glimpse at the apocalyptic images of bodies floating in the sea, innocent people brutally tortured by traffickers in torture camps, children killed during perilous journeys, and families consumed by grief at the loss of their loved ones to imagine the gravity of the human calamity. If we cannot recognise these deaths as human deaths and their suffering as human suffering, I doubt there is an iota of humanity left in us. I truly doubt that humanity will hold any meaning beyond those few who benefit from its destruction.

Second, it is time to recognise that our fate is inextricably intertwined with the lives of those who die. With each death, we lose a significant portion of our humanity. If we get accustomed to these suffering and normalise them, it is because we have lost sight of our own humanity and mortality. This might sound like an emotional plea, but it’s actually a warning. It is a warning against an irrevocable exodus from humanity to catastrophic raciality.

Thirdly, overcoming this human calamity is not the responsibility of only those who suffer its consequences or those who smuggle them. Rather, it is the responsibility of all humanity. Those who create the conditions for this necropolitical spectacle bear the greatest responsibility towards those whom their (in)actions dehumanise.

Finally, dealing with this challenge necessitates a profound change. It requires warmongers, dictators, and their masters to silence their guns and stop creating refugees in the first place. It requires acknowledging the violence of (b)ordering and sharing culpability for this human calamity. It requires governments to take responsibility for their catastrophic abdication of responsibility and for transforming politics into a politics of death. The media and journalists can come out of the shadows of political scandals and speak up for, and with, those yearning to breathe. Ordinary citizens must demand justice for all.

Hyab Teklehaimanot Yohannes, Research Associate, University of Glasgow.

16 June 2023

Source: blogs.law.ox.ac.uk