By Olivia B. Waxman

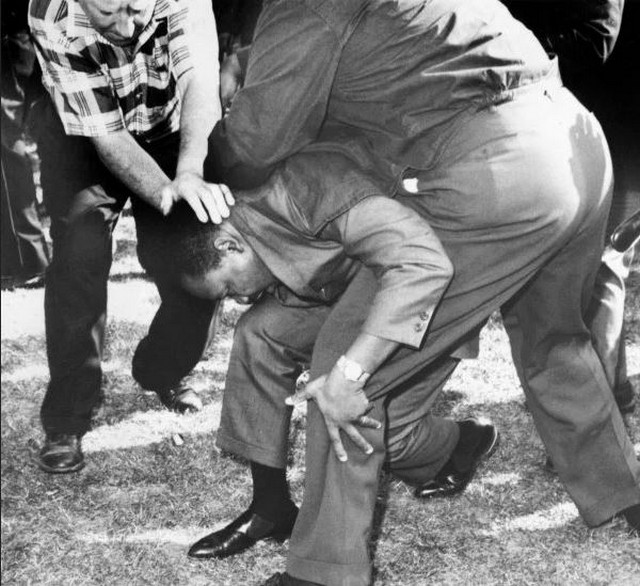

Though such was not the case during his lifetime, it’s uncontroversial today to note that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was an American hero of the civil rights movement, a hero whose birth is celebrated by Americans each year with the national Martin Luther King Jr. Day holiday. More than perhaps any other American, King has come to represent peace — which is just one reason why this image of him brought to his knees in Chicago is so shocking. The story behind the image makes it all the more so.

Though King’s early, more famous efforts for the civil rights movement were concentrated in the American South, from the Montgomery bus boycotts in the late 1950s to his work in Mississippi with the Freedom Riders, this photograph was not taken there. Instead, it dates to a period during which he experienced discrimination that was, in some ways, worse — after his shift to focus on Northern cities after the Voting Rights Act was signed on Aug. 6, 1965.

The tipping point for the shift? “The explosion in Watts really captured the attention of Dr. King,” says James R. Ralph Jr., professor of history at Middlebury College and an author of The Chicago Freedom Movement: Martin Luther King Jr. and Civil Rights Activism in the North.

Yet Chicago seemed like a logical starting point for his efforts in the North, as King later wrote, because, “It is reasonable to believe that if the problems of Chicago, the nation’s second largest city, can be solved, they can be solved everywhere.” To raise awareness of poor living conditions for the city’s African Americans, he himself moved into an apartment in Chicago’s West Side neighborhood of Lawndale. “We don’t have wall-to-wall carpeting to worry about, but we have wall-to-wall rats and roaches,” the Chicago Tribune reported King saying shortly after he moved in on Jan. 26, 1966. King called for “the unconditional surrender of forces dedicated to the creation and maintenance of slums.”

The Chicago campaign — the slogan for which was, at one point, simply “End Slums” — became known as the Chicago Freedom Movement, a collaboration between King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Chicago’s Coordinating Council of Community Organizations. One of its leaders was James Bevel, who had been an architect of the Children’s Crusade that was part of the May 1963 March on Birmingham. That summer in Chicago, two marches helped get the word out about what local civil rights activists were fighting for.

On July 10, 1966, more than 30,000 braved the 98-degree heat wave to hear King speak at a rally at Soldier Field. “We are here because we’re tired of living in rat-infested slums,” he said. “We are tired of having to pay a median rent of $97 a month in Lawndale for four rooms while whites in South Deering pay $73 a month for five rooms… We are tired of being lynched physically in Mississippi, and we are tired of being lynched spiritually and economically in the North.”

Then the crowd followed King to City Hall, where he taped a list of demands to an entrance way. They included increasing the supply of housing options for low and middle-income families, rehabbing public housing amenities, and “Federal supervision of the nondiscriminatory granting of loans by banks and savings institutions.”

A few weeks later came a second march — the occasion for one of his most famous quotes from that campaign, as well as the shocking image seen above.

On Aug. 5, 1966, in Marquette Park, where King was planning to lead a march to a realtor’s office to demand properties be sold to everyone regardless of their race, he got swarmed by about 700 white protesters hurling bricks, bottles and rocks. One of those rocks hit King, and his aides rushed to shield him, as the photo shows.

“The blow knocked King to one knee and he thrust out an arm to break the fall,” the Chicago Tribune reported at the time. “He remained in this kneeling position, head bent, for a few seconds until his head cleared.”

Afterward, King told reporters, “I’ve been in many demonstrations all across the South, but I can say that I have never seen, even in Mississippi and Alabama, mobs as hostile and as hate-filled as I’m seeing in Chicago.”

The virulence of that hatred can be surprising in light of the fact that many African Americans had migrated North, to cities like Chicago, to flee the South. From the perspective of civil rights activists, Ralph argues, “You can argue it was easier to identify the visible problems and laws that were disenfranchising people in the South. In the North, it was more muddied, more difficult to find a single thread you can pull out.”

King expressed that idea when he looked at the hostility from the perspective of whites. “As long as the struggle was down in Alabama and Mississippi, they could look afar and think about it and say how terrible people are,” he wrote later in his autobiography. “When they discovered brotherhood had to be a reality in Chicago and that brotherhood extended to next door, then those latent hostilities came out.”

These fair housing demonstrations gradually started to take place in other nearby cities, such as Louisville and Milwaukee. The Chicago activists even got street gang members to serve as marshals at the 1966 open housing marches in an effort to redirect their energies. Among the campaign’s other accomplishments were efforts to organize tenant unions, so residents could stand up to landlords about things like peeling lead-based paint on their walls, and the launch of Jesse Jackson’s career, as he helped run the Windy City’s chapter of a campaign to combat discriminatory hiring practices.

President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Fair Housing Act into law on April 11, 1968, one week after King’s death. Yet some experts see the Chicago campaign’s effectiveness as mixed, because the problems that the activists tried to combat there have not gone away.

“Did that legislation equalize opportunities? No, but it was an important step, and fair housing groups that had been working before then now had congressional backing,” as Ralph puts it. “Did it end the slums? No, so [the movement] was not successful that regard. But there were substantial strides taken forward.” Peter Ling, a Martin Luther King biographer, has called the Chicago campaign the civil rights leader’s “most relevant campaign” for today’s world.

As Claybourne Carson, editor of the King Papers, put it in his foreword to The Chicago Freedom Movement, the fact that these problems still exist are not King’s fault. “It is also,” he wrote, “the failure of those of us who have outlived him.”

16 January 2020

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com.

Source: time.com