By Norman Solomon

In 1980, when I asked the press office at the U.S. Department of Energy to send me a listing of nuclear bomb test explosions, the agency mailed me an official booklet with the title “Announced United States Nuclear Tests, July 1945 Through December 1979.” As you’d expect, the Trinity test in New Mexico was at the top of the list. Second on the list was Hiroshima. Third was Nagasaki.

So, 35 years after the atomic bombings of those Japanese cities in August 1945, the Energy Department—the agency in charge of nuclear weaponry—was categorizing them as “tests.”

Later on, the classification changed, apparently in an effort to avert a potential PR problem. By 1994, a new edition of the same document explained that the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki “were not ‘tests’ in the sense that they were conducted to prove that the weapon would work as designed… or to advance weapon design, to determine weapons effects, or to verify weapon safety.”

But the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki actually were tests, in more ways than one.

Take it from the Manhattan Project’s director, Gen. Leslie Groves, who recalled: “To enable us to assess accurately the effects of the bomb, the targets should not have been previously damaged by air raids. It was also desirable that the first target be of such size that the damage would be confined within it, so that we could more definitely determine the power of the bomb.”

A physicist with the Manhattan Project, David H. Frisch, remembered that U.S. military strategists were eager “to use the bomb first where its effects would not only be politically effective but also technically measurable.”

For good measure, after the Trinitybomb test in the New Mexico desert used plutonium as its fission source on July 16, 1945, in early August the military was able to test both a uranium-fueled bomb on Hiroshima and a second plutonium bomb on Nagasaki to gauge their effects on big cities.

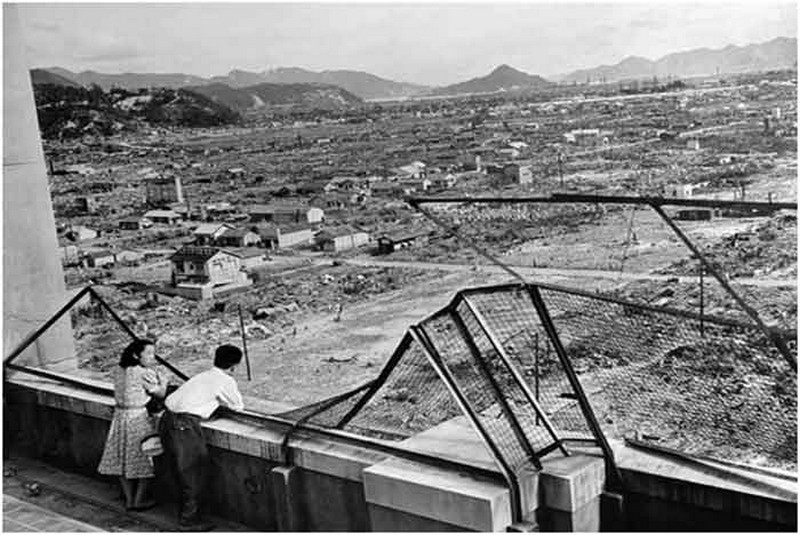

Public discussion of the nuclear era began when President Harry Truman issued a statement that announced the atomic bombing of Hiroshima—which he described only as “an important Japanese Army base.” It was a flagrant lie. A leading researcher of the atomic bombings of Japan, journalist Greg Mitchell, has pointed out: “Hiroshima was not an ‘army base’ but a city of 350,000. It did contain one important military headquarters, but the bomb had been aimed at the very center of a city—and far from its industrial area.”

Mitchell added: “Perhaps 10,000 military personnel lost their lives in the bomb but the vast majority of the 125,000 dead in Hiroshima would be women and children.” Three days later, when an atomic bomb fell on Nagasaki, “it was officially described as a ‘naval base’ yet less than 200 of the 90,000 dead were military personnel.”

Since then, presidents have routinely offered rhetorical camouflage for reckless nuclear policies, rolling the dice for global catastrophe. In recent years, the most insidious lies from leaders in Washington have come with silence—refusing to acknowledge, let alone address with genuine diplomacy, the worsening dangers of nuclear war. Those dangers have pushed the hands of the Doomsday Clock from the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists to an unprecedented mere 90 seconds to cataclysmic Midnight.