By Shiraz Durrani

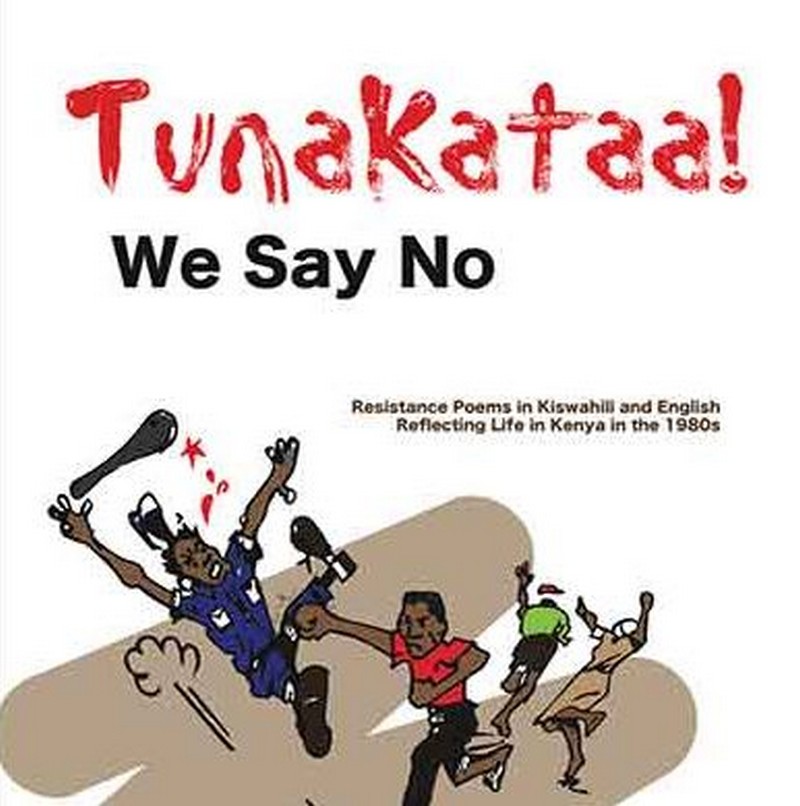

Preface to the book by Durrani, Nazmi: Tunakataa! We Say No! Resistance Poems in Kiswahili and English Reflecting Life in Kenya in the 1980s. Forthcoming: Nairobi: Vita Books.

[Tunakataa: Kiswahili – ‘We Say No!]

Kenyans have been saying Tunakataa/We Say No to colonialism and imperialism for over 500 years, ‘No’ to all the exploitation and oppression that are part of these oppressive systems. But the greed and the brute force of the Portuguese initially, then British and USA imperialism blinded their eyes and closed their ears to the voice of people. Resistance was the only way of challenging the invading forces — political, military, religious, cultural, among others . It was the taking up of arms by Mau Mau in the late 1950s that finally brought independence to Kenya. But not an end to capitalism, long planted by British colonialism through various underhand means. The suppression of the rights of working people, the looting of their land and wealth that are the hallmark of capitalism, remained after independence, this time ably managed by the former homeguard collaborators with colonialism, now reincarnated as the rulers of independent Kenya. But they did not have it all their own way. Resistance which had been the characteristic feature during the colonial period, could not be suppressed by the new ruling class although they continued the use of the same instruments of suppression that colonialism had used: massacres, murders, disappearances and targeting resistance organisations, their leaders, their ideologies and their culture. And people have continued to say ‘No’ to all this, as does Nazmi Durrani in these poems.

An understanding of this intense repression under President Daniel arap Moi can provide the background to these poems of resistance. UMOJA (1989, 15) gives a good summary of the first ten years of President’s Moi’s rule which created the conditions reflected in these poems:

Over the ten years, the Moi-KANU regime has been involved in i) torture, killings, political executions and massacres; ii) arrests, political jailings and detentions without trial on a scale that can only mean that Kenya has been under an undeclared state of emergency; iii) the crushing of all independent democratic social organisations; iv) the rigging of elections even under the one-party state to ensure only those candidates loyal to Moi himself go through and v) the cynical arbitrary and frequent changes of laws and constitution to effect, justify and rationalise the above and to meet all the subjective whims of Dictator Moi.

The regime then used the coup of 1982 as an excuse to suppress all opposition to its bloody rule, as UMOJA (1989, 17) shows:

The regime used the coup attempt of August 1982 as a cover for the silencing of all democratic opposition. After suppressing the coup, the regime let loose its loyalist forces on the population. They stopped people in the streets. They raided people’s homes, confiscated a large quantity of people’s property and raped women. A busload of university students was gunned down. No Kenyan seriously believes the official lies about a toll of 159. Church and other independent sources put the death toll at about 2,000. Certainly all the mortuaries in and around Nairobi were full of dead bodies of civilians. It should be emphasised that these deaths had nothing to do with the acts of suppressing the coup attempt – all the killings took place after the coup had been put down.

It is against this background of brutal suppression of people that Nazmi Durrani’s poems need to be read and seen as well, as part of the history of post-independence resistance. Durrani was part of the organised resistance of the underground December Twelve Movement (DTM). The Appendix to this book reproduces an earlier article that touched on some aspects of Durrani’s life and his political activities. This included turning his flat in Ngara into a centre of political activities of the Ngara Cell of the December Twelve Movement. But one cannot see the writer, the activist and his political work in isolation from the resistance movement in Kenya at that time. He was part of organised resistance and his activities reflected the aims and visions of December Twelve Movement (DTM). A background to DTM is as important as the brutality of Moi in setting the poems in their historical and political context. This is given by Durrani and Kimani (2021, 20):

Earlier attempts by radical groups to continue the vision of Mau Mau within KANU had failed, reflecting the total surrender of the comprador class to imperialist interests. It became the historical role of underground resistance movements to articulate the new phase in Kenyan politics where open tradition of organized underground resistance in Kenya goes back to the beginning of the twentieth century and continued throughout the colonial period and post-independence. Moreover, it carried on throughout the period of Kenyatta’s regime [as it] consolidated its neo-colonial grip on the country. Among the key underground movements was the December Twelve Movement (DTM) which later emerged as Mwakenya.

Within this overall context of resistance, DTM carried out its political and ideological work in various ways, again as described by Durrani and Kimani (2021, 20-21):

DTM opposed the capitalist outlook of the ruling class and their party. It was active in articulating its ideological position, policies, and outlook, not only among its active members grouped in secret cells but also in disseminating these to its actual and potential supporters among the masses. It was not a mass movement, and only accepted into its membership those who showed a clear grasp of its ideological stand and were willing to put into practice their commitments. The emergence of DTM marked the end of the attempts by democratic forces to form legal opposition parties. DTM’s activities and ideological stand are best seen in its publications.

As a member of this resistance movement, Durrani was active in a number of fields — writing on, and documenting, comprador violence and people’s resistance; taking part in resistance theatre; setting up and managing an underground library of socialist and communist literature and, as mentioned earlier, turning his flat into a resistance resource. The poems included in this book reflect one of the cultural aspects of his political work. He wrote many articles — in Gujarati, English and Kiswahili — on resistance leaders in Kenya; he wrote short stories and poems some of which were published in the local media under pseudonyms. He wrote several children’s short stories. In writing the poems included in this book, he combined a number of his activist pursuits. Many of the poems record historical events of police brutality and people’s resistance to these. Some poems record the events which would otherwise have been forgotten, for example Monica Njeri, The Battle of the Tusker Bus Stop, Workers of Shimanzi and Mnjala Killed. Others raise awareness of the state of exploitation under capitalism, for example, Flood of Profits; yet others take up issues of classes and class struggle, such as Class Struggle , Two Towns, We and You and Who Are We? The poems also depict the victories of the struggles, for example Victory at Chinga while others look ahead to the coming revolution, such as Thunder of Revolution. They also reflect the struggles for liberation not only in Kenya but around the world, for example Comrade Samoral the African Hero,The Nicaraguan Revolution Will Be Victorious, Liberation Wars of the Palestinians, The Great Terrorist Reagan and several others on South Africa. Educating people about capitalism as the reason for their poverty is always present, for example in Exploitation is the Reason for Poverty and Oppression and Resistance are Inseparable.

Yet another aspect that is significant in these poems is the language used. The poems were originally written in Kiswahili, later translated by the author into English. This indicates the audience that they were aimed at — workers, whose struggles the poems reflect.

The question then is: are these poems to be seen as literature, history or politics? Library cataloguers, historians and students of literature can argues over this. At one level, they are a historical record of the 1980s Kenya. They record the daily lives of working people under state repression, their reactions, their hopes and aspirations. They record how they survived under such oppression and kept their hopes alive for a better future. At the same time, they are political communication depicting exploitation of working people and their resistance. The poems are not one or the other: they are history, they are a call to action, they are a lament and they offer hope in a grim, oppressive world. To say ‘no’ to exploitation is ultimately a statement of political commitment, of being positive about the prospect of liberation, of exhorting people everywhere to rise up agains all forms of suppression, oppression and exploitation. And the context of all this cannot be ignored or forgotten: It is saying ‘No’ to capitalism and imperialism, which is another way of saying ‘Yes’ to liberation under socialism.

Durrani emerges from these poems as a keen observer, listener and learner who takes in and re-tells, the experiences of working people and their struggles. He becomes at one with the oppressed and becomes their voice. He shows those who struggle and those who fall by the wayside and those who triumph, however temporarily. The struggle goes on and the author is always there to see, listen and record.

The spirit of the book is captured by the poem It is Our Right to Fight for Our Rights. It also indicates the reason for waging a war against capitalism and imperialism. Listen to the voice of those struggling for liberation: It’s the right of each and everyone To have food clothing and shelter This is a right, the very foundation of life.

Illustration: The Nation is Like a Cow ( By Nazmi Durrani)

It is Our Right to Fight for Our Rights

It’s our right to fight for our rights

it’s our duty to fight for our rights

Not to fight for our rights is a crime

We cannot uphold our rights without struggle

It’s the right of each and everyone

To have food

Clothing and shelter

This is a right, the very foundation of life

It’s the right of people to get these necessities

By way of work, by sweating for them

Not through charity or exploitation

Work is the right of all

If denied the right to work

People have the duty to change

The system that denies them this right

it’s our right to fight for our rights

Illustration: Shamba Langu! (By Nazmi Durrani)

The poems, the history they depict, the hopes and the vision they carry reflect the reality of life for working people in Kenya in the 1980s. But these are not so different from the situation of working people in Kenya today — or indeed of the working people around the world. Capitalism uses the same tactics wherever it goes; it creates the same exploitation and oppression wherever it goes. And the cry of the people, Tunakataa!, We Say No also follows capitalism everywhere. There is a universality in these poems that reflects the exploited world as it resists capitalism and struggles for socialism. The final word is left to the poem, We Say No:

Sisi wafanyakazi na mafalahi

Ni sisi tu tunazalisha mali

Tunakataa, tunakataa, tunakataa

Kukubali zinyakuliwe na mabepari

Sisi wafanyakazi wa karakana

Tunatoa jasho kuzalisha bidhaa

Tunakataa, tunakataa, tunakataa

Kuruhusu faida ziende Ulaya

We the workers and peasants

It is we who produce wealth

We refuse, refuse totally

To let it be stolen by capitalists

Today, over two decades later, it is difficult to imagine the situation for working people in Kenya in the 1980s, the on-going repression from the Moi government and the resistance from the working people. It is then also difficult to see the full significance of the events shown in these poems. Some historical notes and references have been added in the book under the heading, the Kenya of the Poems, in order to capture the reality of that time. The poems then become a commentary on the life and times of Kenyan working people and their struggles. But it is not only history — it is also the present in Kenya and many other parts of Africa. The relevance of the poems to the reality of today’s Africa is confirmed by two members of the Learning and Teaching WhatsApp Group (L&T). First, Brian Mathenge from Kenya responds to one of the poems, December 12:

This is a powerful one, by Nazmi Durrani, that our freedom was hijacked, blood and sacrifices of our martyrs betrayed.The last bit is encouraging:

We have no doubt we shall win true freedom

But blood must be shed yet again

We will have to fight with arms once again

We’ve learned from history, we won’t be deceived again.

This can be distributed within our circles.

When asked if the poems are relevant to Kenya and Africa in 2020, Mathenge adds:

Yes, they are, there are few progressive history books or revolutionary publishing media in present Kenya, due to deliberate censorship by the state, making it difficult for the young generation to connect with their past, get inspired and keep the conviction of struggle.

With these few, rich and inspirational articles we draw a lot of strength to keep the struggle going… This [referring to the book, Tunakataa!] would be one of the powerful set of literature, it would be helpful, especially in the generational inheritance of struggle. There’s so much that is untold and scrapped from History.

Another member of the L&T Group, Ivy Himani from Zambia gives her views:

It’s very much relevant… most African countries are having the same cry. In Zambia, it’s been years of independence but that’s just in books.In reality, slavery has just been modernized where a few are privileged at the expense of others.

That is the voice of youth in Africa today. They join the demands for justice and equality. Tunakataa! indeed, is the voice of Africa and African youth today.

References

Durrani, Shiraz (2018): Kenya’s War of Independence: Mau Mau and its Legacy of Resistance to Colonialism and Imperialism, 1948-1990..

Durrani, Shiraz and Kimani Waweru (2021): Kenya: Repression and Resistance from Colony to Neo-colony,1948–1990. The Kenya Socialist, 3, 2021, 7-25. Available at: https://vitabooks.co.ke/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/The-Kenya- Socialist-Issue-3-2021.pdf.

UMOJA (1989): Moi’s Reign of Terror: A Decade of Nyayo Crimes against the people of Kenya. London: Umoja (Umoja wa Kupigania Demokrasia Kenya/ United Movement for Democracy in Kenya. Background Document No. 2.

Shiraz Durrani is a Kenyan political exile living in London. He has worked at the University of Nairobi as well as various public libraries in Britain where he also lectured at the London Metropolitan University.

27 September 2023

Source: countercurrents.org