By Richard E. Rubenstein

When I taught political science in my younger days, the received wisdom was that the major U.S. political parties were loose coalitions of diverse groups bound together principally by their common interest in acquiring political power: i.e., governmental offices and the spoils of office. What they notably lacked was the sort of ideological, cultural, and socioeconomic unity that characterized party organizations in many other nations. As a result, except during unusual periods like the runup to the Civil War and the era of the Great Depression, America’s Republican and Democratic parties tended to resemble each other like Tweedledum and Tweedledee. One could either celebrate this incoherence or criticize it, but the lust for office and a taste for unprincipled deal-making long seemed unshakeable political norms in the U.S.A.

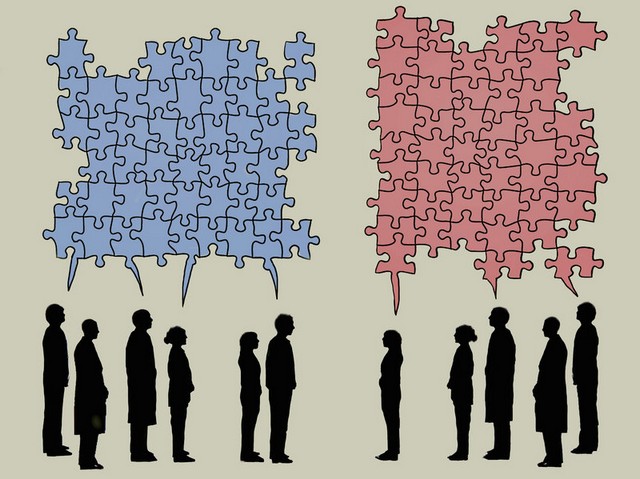

No longer! Although President Trump is demanding a recount of votes, the current national elections will almost certainly expel him from the White House and make Joe Biden the 46th U.S. President. They will also confirm Democratic control of the House of Representatives and produce a closely divided Senate, with Vice-President Kamala Harris (the first woman and first person of color to occupy that office) in a position to break tie votes as the Senate’s presiding officer. But the elections’ real headline is the division of the American electorate into two groups almost exactly the same size (approximately 70 million in each camp), which are not describable merely as ad hoc coalitions of power-seeking “interest groups.”

On the contrary, those now identifying themselves either as Republicans or Democrats have come to think of themselves and their comrades as embodying identical or closely related ideological commitments, cultural characteristics, and moral or religious values. They have become modern tribes – a development that is transforming American politics and the politics of many other nations as well.

Some may consider this reference to tribalism an exaggeration, but it is not. Tribalism is what happens when competing social groups identify themselves as peoples or “nations,” with each group embracing a narrative that expresses a commonly accepted version of its history, grievances and destiny. Tribalism emerges when each group comes to trust and patronize its own sources of information and opinion and to distrust “hostile” sources, thus producing separate and conflicting images of the world. Neo-tribal groups consider their own members trustworthy, caring brothers and sisters, while branding outsiders deceitful, cruel, or malicious. The conflicts they engage in with other groups thus come to look far more like ethnic, racial, or religious conflicts than traditional public policy disputes.

This is why – to take one small example – scholars report that “fact checking” rarely changes the minds of group members committed to their own version of the facts. As one researcher puts it, political party affiliation is now as strong as religious identity. “You’re not going to change your religion if somebody tells you that Moses didn’t actually have the Ten Commandments.”[i] The rise of neo-tribalism also helps to explain why conflicts formerly framed as differences over public policy tend to be reframed in terms of the defense of a threatened way of life. The debate about gun control, for example, once considered a dispute about the costs and benefits of firearms regulation now appears to partisans on both sides to be a conflict pitting “civilized” against “uncivilized” groups, with the definition of “civilized” varying according to the political and ethical values of one’s tribe.

The response of each group to the COVID pandemic provides another example of neo-tribal thought. Witnessing the unwillingness of many Trump followers (especially in rural areas) to wear masks, and noting their powerful impulse to reopen workplaces, places of entertainment, churches, and schools as early as possible, members of the liberal tribe see the right-wingers as self-destructive, reckless with other people’s lives, obsessed with primitive ideas of macho freedom, and more interested in moneymaking than lifesaving. To those same conservatives, however, the liberals who label them uncivilized are an effete, overeducated, self-indulgent elite able to work remotely from their homes – snobs looking down their noses at those dependent for their survival on open schools and workplaces. Each side considers the other a deviant tribe and their own group the true America. Stereotyping is the rule on both sides and looking into the mirror the exception.

Many Americans interested in peace and progress are now greeting Donald Trump’s departure from office with sighs of relief and prayers of thankfulness. This is justified, since Trump is a dangerous figure whose attack on the electoral system in the late stages of the electoral campaign resembled nothing so much as the fascist assault on parliamentary institutions in the 1920s and 1930s. But this President did not create American neo-tribalism, and it will not disappear with his departure from office. To create a national community linked organically to an international community also in the process of creation will the task of the next generation of peace- and justice-makers.

The key questions that will soon confront the Biden administration, and that must interest everyone interested in the peaceful resolution of conflicts, are what is causing the pronounced trend toward neo-tribalism, and what can be done to resolve or transform neo-tribal conflicts. Four brief suggestions may be worth considering:

1. Admit that we do not yet have good answers to these questions. The first requirement, yet to be fulfilled, is to recognize the transformation of politics in the direction of neo-tribalism and our own tribal commitments. This immediately suggests that traditional methods of political dispute-resolution (power-based bargaining, judicial interpretation of rules, circulation of elites, and so forth) are unlikely to be effective. The goal here must be conflict prevention to avoid further developments that could lead to serious civil violence.

2. Recognize that neo-tribal conflicts are not cultural/religious as opposed to socioeconomic/political, but explosive combinations of class-based and culture-based antagonism. The American news media, which have an aversion to uttering the words “working class,” note that the majority of supporters of President Trump and the Republican party are white people (white men in particular) without college degrees, while college-educated men and women (women in particular) tend to support the Democrats. The task immediately confronting conflict resolvers is to gain a better understanding of the intimate links between social class and political, racial, and religious identities, and to discuss the systemic changes that will be necessary to satisfy each group’s basic needs.

3. Understand that elections and the advent of new leaders will not produce the needed systemic changes unless politics, on the deepest level, becomes the avocation of masses of people, something to be practiced continuously in a spirit of communal collaboration and experimentation, not reserved for periods of electoral competition. In nations like the United States, democracy will not be “restored”; it will be redefined. The task of redefinition must involve searching for examples of sociopolitical innovation in one’s own history (in the America of the New Deal, for example) and in other nations. Have the Americans nothing to learn about social welfare policy from Europeans, or about how to defeat a plague from Asians? Such questions answer themselves.

4. Recognize that from Roman times until the present, the rise of neo-tribal conflict has been a symptom of imperial decline. It is particularly important for Americans to “connect the dots” that run between the existence of an empire that maintains 800 or so military bases in eighty nations and consumes close to $1 trillion annually in military expenditures and the problems of communities in virtually every part of the nation plagued by poverty, precarity, poor schools, familial discord, overstressed social services, and a decaying infrastructure – all conditions that inflame conflict between groups struggling to maintain basic levels of economic and cultural security. The American system will not be rebuilt so long as it remains subordinate to the demands of the American Empire.

Equally important, the Empire’s decline raises the same sort of questions that have faced other peoples in a post-imperial context: if we are not defined by our role as a global or regional hegemon, who are we? Who do we want to be? Tribalism is one answer to that question, although a very poor one.

Goodbye (and good riddance), Mr. Trump. Welcome, Mr. Biden. Now that the election is over, it is time to get down to business. And the first order of business, in my view, will be to confront and consider how to transcend America’s intense neo-tribalism.

NOTE:

[i] Farah Stockman in New York Times, 11 Sep 2020 (“What I Learned from a List of Trump Accomplishments”)

_______________________________________

Richard E. Rubenstein is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment and a professor of conflict resolution and public affairs at George Mason University’s Jimmy and Rosalyn Carter Center for Peace and Conflict Resolution.

9 November 2020

Source: www.transcend.org