By Farooque Chowdhury

Condition of labor in today’s world is not difficult to gauge. News on labor’s working and living condition is in abundance, which help comprehend the conditions within which labor survive in the present day world.

State of societies also gives a picture of labor’s condition. Afghanistan or Iraq, Libya or Syria, Greece or Ukraine, Egypt or Sudan, the UK or the USA is only a few examples. A number of societies have already experienced imperialist onslaught or financial and other crises related to capitalism or the so-called austerity measures, which brought devastation and death, eviction from home and unemployment, slashed real wage and anti-labor legislation. Everyday existence is the only question that life faces there in these societies. There’s little scope for labor to get mobilized, chalk out and raise demands, express opinion. A number of laws in a number of advanced capitalist societies virtually make unionization difficult, which is hard to identify at first and easy glance. In countries, unionization is falling. It requires serious search to get the fact from these societies. Modern slaves are now well-known fact in many modern economies.

Another angle of the issue also helps see the present condition of labor: profit. The quantity of profit shows the extent labor was robbed over the years as profit comes from whatever surplus labor is appropriated. Moreover, there’s monopoly superprofit – “surplus of profits”, as Lenin defines, “over and above the capitalist profits that are normal and customary all over the world.” (“Imperialism and the split in socialism”, 1916) It comes by intensively appropriating labor, over-pricing and -valuing, and robbing non-monopoly enterprises, small producers, countries having productive investment by monopolies, by financial operations. “A handful of wealthy countries […] have developed monopoly to vast proportions, they obtain superprofits […] they ‘ride on the backs’ of hundreds and hundreds of millions of people in other countries […]” (ibid.) John Perkins in his The New Confessions of an Economic Hit Man Paperback tells the ways trillions of dollars were robbed from countries. It’s a story from Ecuador, Honduras, Seychelles, Vietnam. It’s a story from Turkey. Are other countries free from the loot? Greece, Spain, Portugal? Rest of the countries within clutch of imperialism and with colluding governments? People including labor are coerced to submit to “policies that make the rich richer and the poor poorer.” Imperialist wars and interventions have aggravated the situation. At the end, there remains profit and superprofit.

Let’s look at a randomly picked portion of profit/superprofit over the last few years:

“US banks posted $40.24 billion in net income during the second quarter, the industry’s second-highest profit total in at least 23 years, according to data from research firm SNL Financial. The latest profits are just below the record $40.36 billion recorded in the first quarter of 2013.” (The Wall Street Journal, “U.S. Bank Profits Near Record Levels”, by Robin Sidel & Saabira Chaudhuri, August 11, 2014)

New York Fed economists Tobias Adrian, Michael Fleming, Or Shachar, Daniel Stackman and Erik Vogt wrote in the blog Liberty Street Economics (“Changes in the Returns to Market Making”): Profits have soared since the global financial crisis at the five biggest US banks. From 2009 to 2014, the combined net income of J.P. Morgan, Citigroup, Bank of America, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley annually averaged $41.73 billion, up from annual average of $25.08 billion from 2002 to 2008. (The table on net income for the five largest US dealers exceeds pre-crisis levels) (Reuters, “Profits at big U.S. banks soar since crisis: New York Fed”, by Richard Leong, October 7, 2015)

Citing Federal Deposit Insurance Corp Matthew Heller writes: The US banking industry finished 2015 with a strong fourth quarter. In its latest Quarterly Banking Profile, the FDIC said federally-insured commercial banks and savings institutions reported aggregate net income of $40.8 billion in the fourth quarter of 2015, up $4.4 billion (11.9%) from a year earlier. The proportion of banks that were unprofitable in the fourth quarter fell from 9.9% a year earlier to 9.1%, the lowest level for a fourth quarter since 1996. (“U.S. Bank Profits Climb 11.9% to $40.8B”, CFO.com, CFO Publishing, New York, February 24, 2016)

Swiss banks saw their profits rise during 2014 to close to 19.5 billion Swiss francs although their staff count declined in the year. Announcing its annual update on Swiss banks, the country’s central bank SNB (Swiss National Bank) said on June 18, 2015: 246 out of the 275 banks in Switzerland recorded an annual profit, taking total profit to CHF 14.2 billion in 2014, from CHF 11.9 billion in the previous year. The number of staff working in banks decreased by 1,844 to 125,289. (The Economic Times, “Swiss banks’ profit rises; staff count down”, June 18, 2015)

Swiss bank UBS on February 2, 2016 reported net profit for 2015 up 79 percent at 6.2 billion Swiss francs, ahead of a consensus forecast compiled by Reuters of 5.75 billion Swiss francs. The wealth management business reported its best annual pre-tax profit since 2008. (CNBC.com, “UBS profit up 79% amid ‘paralyzing’ volatility”, by Julia Chatterley & Antonia Matthews”, February 2, 2016)

Canada’s top banks saw their fourth-quarter profits edge higher in 2014. Combined, Canada’s five biggest banks — Royal Bank, TD Bank, Scotiabank, Bank of Montreal and CIBC — earned $7.4 billion of net income during the quarter, up slightly from $7.3 billion a year ago. Their profits for the year climbed to a total of $31.7 billion, from $29.2 billion last year. National Bank, the country’s sixth largest lender, reported fourth-quarter net income of $330 million, up from $320 million a year ago. The bank also boosted its dividend for the third time in the past year. (The Canadian Press, “Canadian Banks’ Profits Top $31.7 Billion In Fiscal Year, But ‘Challenges’ Loom”, by Alexandra Posadzki, 12/05/2014 & with update 02/04/2015)

Australia’s big banks will next week hand down interim profits of almost $16 billion (The Australian, “Big banks set to face more scrutiny as profits near $16bn”, by Michael Bennet, April 25, 2016)

Armaments industries are a good indicator of the joyful journey of profit. A report by Rob Garver in The Fiscal Times said:

“[H]ow well have U.S. defense firms done in the past few years? To put it in context, in the past 24 months, the U.S. stock market has been on a nearly unprecedented tear. Since April of 2013, the Standard & Poor’s 500 index has soared, increasing in value by more than 30 percent. […]

“Since April of 2013, the Dow Jones U.S. Aerospace and Defense Total Stock Market Index has grown at double the rate of the S&P, increasing in value by 60 percent”. (“U.S. Defense Industry Outperforms S&P by 100 Percent”, April 20, 2015)

Another report, two years prior to the above report, in USA Today said:

“The business of war is profitable. In 2011, the 100 largest contractors sold $410 billion in arms and military services. Just 10 of those companies sold over $208 billion. Based on a list of the top 100 arms-producing and military services companies in 2011 compiled by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), 24/7 Wall St. reviewed the 10 companies with the most military sales worldwide.

“These companies have benefited tremendously from the growth in military spending in the U.S., which by far has the largest military budget in the world. […] SIPRI noted that between 2002 and 2011, arms sales among the top 100 companies grew by 51%.”

Based on the SIPRI report, 24/7 Wall St. reviewed the 10 biggest weapons companies, looked at sales figures for two years through 2011, among other metrics. Following “are the 10 companies that profit the most from war”:

10. United Technologies – arm sales: $11.6 billion, total sales: $58.2 billion, gross profit: $5.3 billion, total workforce: 199,900.

9. L-3 Communications – arm sales: $12.5 billion, total sales: $15.2 billion, gross profit: $956 million, total workforce: 61,000.

8. Finmeccanica – arm sales: $14.6 billion, total sales: $24.1 billion, gross profit: $ 3.2 billion, total workforce: 70,470.

7. European Aeronautic Defense and Space Company – arm sales: $16.4 billion, total sales: $68.3 billion, gross profit: $1.4 billion, total workforce: 133,120.

6. Northrop Grumman – arm sales: $21.4 billion, total sales: $26.4 billion, gross profit: $2.1 billion, total workforce: 72,500.

5. Raytheon – arm sales: $22.5 billion, total sales: $24.9 billion, gross profit: $1.9 billion, total workforce: 71,000.

4. General Dynamics – arm sales: $23.8 billion, total sales: $32.7 billion, gross profit: $2.5 billion, total workforce: 95,100. The company announced layoffs in early March, blaming mandated federal budget cuts.

3. BAE Systems – arm sales: $29.2 billion, total sales: $30.7 billion, gross profit: $2.3 billion, total workforce: 93,500. BAE noted that its outlook “constrained”, “likely due to the diminished presence in international conflicts and government budget cuts.”

2. Boeing – arm sales: $31.8 billion, total sales: $68.7 billion, gross profit: $4 billion, total workforce: 171,700.

1. Lockheed Martin – arm sales: $36.3 billion, total sales: $46.5 billion, gross profit: $2.7 billion, total workforce, 123,000. “In the fall of 2012, the company planned on issuing layoff notices to all employees before backing down at the White House’s request.” (“10 companies profiting the most from war”, by Samuel Weigley, 24/7 Wall St., March 10, 2013)

A year later, a Bloomberg News report by Richard Clough said:

“Led by Lockheed Martin, the biggest U.S. defense companies are trading at record prices as shareholders reap rewards from escalating military conflicts around the world.

“Investors see rising sales for makers of missiles, drones and other weapons as the U.S. hits Islamic State fighters in Syria and Iraq, said Jack Ablin, chief investment officer at Chicago-based BMO Private Bank.

“‘As we ramp up our military muscle in the Mideast, there’s a sense that demand for military equipment and weaponry will likely rise,’ said Ablin, who oversees $66 billion including Northrop Grumman and Boeing shares. ‘To the extent we can shift away from relying on troops and rely more heavily on equipment — that could present an opportunity.’

“A Bloomberg gauge of the four largest Pentagon contractors – excluding Boeing … – rose 19 percent this year through yesterday, outstripping the 2.2 percent gain for the Standard & Poor’s 500 Industrials Index.

“Lockheed, the world’s biggest defense company, reached an all-time high of $180.74 on Sept. 19, when Northrop and Raytheon also set records. General Dynamics, the parent company of Maine shipbuilder Bath Iron Works, traded at $129.45 on that day, up from $87.74 a year ago. That quartet of companies and Chicago-based Boeing accounted for about $105 billion in federal contract orders last year, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

“Even with revenue at Lockheed, Raytheon, General Dynamics and Falls Church, Virginia-based Northrop down 4 percent since 2011, non-U.S. sales have climbed 9 percent during that stretch. The four companies also have pared expenses, including reducing their combined workforce since 2011 by 23,000 people, or about 6 percent, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

“‘We haven’t seen so many territories and borders called into question since World War II,’ said BMO Private Bank’s Ablin.” (Portland Press Herald, “U.S. defense industry’s profits soaring along with global tensions” September 25, 2014)

There’s a similar tale of profit-game from Europe. Ron Fraser writes:

“Even as the Greek economy continues its agonizing collapse, with the nation struggling to submit to extreme austerity measures being enforced by its masters in Berlin, the nation’s unelected technocratic government is overseeing a giant fiddle of the books involving the channeling of bailout money into the coffers of Germany’s armaments industry.

“To counter Turkey’s aggression, Greece has spent huge amounts on defense budgets — as much as 4.3 percent of gross domestic product, proportionately the highest among the EU nations.

“Who has been the greatest beneficiary of this defense expenditure? The major supplier of defense equipment to Greece: the German armaments industry.

“How much have EU elites actually manipulated ongoing Greek-Turkish tensions for the advantage of the European Union’s thriving defense industries? As one Greek source observed: “In this volatile game of geopolitics, the bosses of Euro ‘family’ have always been playing the major role in cultivating and manipulating an unguaranteed stability in the area, thus creating market conditions for their influential military industries to flourish. German defense corporations in particular have been major contractors with the Greek (and Turkish) army for more than two decades” (Antibaro.gr, Nov. 29, 2010).

“The facts are that Greece’s coffers have been substantially drained into huge profits for German defense industry barons. This includes multibillion-euro contracts for Greece to purchase big-ticket military hardware ranging from tanks to missiles to naval vessels, including submarines.

“‘All these sum up to hundreds of billions of euros and, under other circumstances, could have been more than enough to balance the Greek budget deficit and even drastically alleviate the external debt,’ that same Greek source observed. ‘One thing is for sure, those billions were added to the profits of German industrialists, bankers and intermediaries.’

“Since that report came to light, the Greek economy has been brought to the brink of catastrophe, with the prospect of inevitable default on its debts being very real by the end of the first quarter of the current year.

“The saving grace for Greece may well be the degree of influence that German defense industry corporate elites and their bankers have in terms of convincing the International Monetary Fund and the European Central Bank to cough up another tranche of euros in their interests. An unnamed source is quoted by German news source Zeit Online as observing that “If Greece gets paid in March the next tranche of funding (€80 billion is expected), there is a real opportunity to conclude new arms contracts” (January 5).

“Zero Hedge reports that, ‘after the Portuguese (another obviously stressed nation), the Greeks are the largest buyers of German war weapons.’ The same source contrasts this huge expenditure by Greece on armaments amid the general state of the Grecian economy, with ‘the country’s doctors only treating emergencies, bus drivers on strike, and a dire lack of school textbooks and the country teetering on the brink of drachmatization […]’ (January 9).

“When the EU was threatened with the collapse of the Greek economy, German defense industry chiefs held the Greeks’ feet to the fire. Rather than cancel out on existing contracts, permitting the release of funds to support basic services within the ailing Greek economy, the German government defense contractors enforced Greece’s contract obligations.

“The effect of this scenario has been that Greece is treating as a priority the payment of its obligations to the German armaments industry using the very bailout funds received to ostensibly revive its dying economy.” (The Trumpet, “German Arms Industry Profits at Greek Expense”, January 11, 2012)

This seemingly endless and unfathomable profit and superprofit have its origin: at the cost of labor. In Greece, how is labor surviving? In Africa, what’s the condition of the diamond diggers? In Spain and Portugal? In India? In the US? Country after country labor, broadly, carries the same story: exploitation and deprivation, low wage and harsh living condition. Uncertainty and indignity are part of labor-life. Labor is exploited so that profit gets generated. Labor is deprived of all aspects of life: material conditions for a livable life and rights.

“An estimated one million diamond diggers in Africa”, say a number of diamond related literature, “earn less than a dollar a day. This unlivable wage is below the extreme poverty line. As a result, hundreds of thousands of miners lack basic necessities such as running water and sanitation. Hunger, illiteracy, and infant mortality are commonplace. Because children are considered an easy source of cheap labor, they are regularly employed in the diamond mining industry. In some areas of Africa, children make up more than a small part of the workforce. One survey of diamond miners in the Lunda Norte province of Angola found that 46% of miners were between the ages of 5 and 16. For children trapped in the diamond mines, life is full of hardship. Children work long days, often six or seven days a week.”

This story – source of cheap labor, long working days, seven days a week – is overwhelming in countries. The so-called informal sector, the “honorable” self-employed, labor in small enterprises, labor facing the threat of outsourcing, competition with illegal and migrant labor create the same story. Slums are one of the easier points to know working people’s life as “a large share of factory workers lives in slums and informal colonies around industrial areas.” (Labour regimes in the Indian garments sector: capital-labour relations, social reproduction and labour standards in the National Capital Region, by Alessandra Mezzadri and Ravi Srivastava, (Report of the ESRC-DFID Research Project ‘Labour Standards and the Working Poor in China and India’), October 2015, published by the Centre for Development Policy and Research) What do the Dhaka-, Cairo-, Manila-, Mumbai- slums show? What do the workers’ life in Ludhiana, Bangalore, Chennai, Tiruppur and Okhla (Delhi) show? It’s a dark, dingy-life. It’s desolate and destitute. And, slums are integral part of exploitative economy.

Europe, economically and politically much advanced and powerful than Asia-Africa-Latin America gives a clearer picture, which helps compare similar situation in the underdeveloped hemisphere. Think Differently, Humanitarian impacts of the economic crisis in Europe, an October 2013 report by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies said:

In 2011, a quarter of EU’s population was at risk, having increased by 6 million since 2009 to 120 million in total. Whilst other continents successfully reduce poverty, Europe adds to it. […]

Almost half of Bulgaria’s population was at risk in 2011. Seventeen EU countries record more than one-fifth of their population as poor or excluded. This includes almost one third of the population in the most recent new member state, Croatia. […]

Poverty is on the increase in France, Romania, Spain, Sweden and many other countries …

The 68-page study report said: Europe is sinking into a protracted period of deepening poverty, mass unemployment, social exclusion, greater inequality, and collective despair as a result of austerity policies. The grave impact of the crisis was not confined to the crisis-ravaged, bailed-out countries of southern Europe and Ireland, but extended to relative European success stories such as Germany and parts of Scandinavia.

European Observatory of Working Life’s report Impact of the crisis on working conditions in Europe (July 9, 2013) covered the 27 EU member states and Norway. The report said:

Throughout this report the following pattern emerges – rising insecurity, less choice, wage freezes and the feeling of “not being all in it together”.

It found “higher levels of work intensity (workload, work pressure and job demands) […] in economically restructuring workplaces”, and diminished “choice possibilities of workers”.

The report Destitution in the UK by Suzanne Fitzpatrick, Glen Bramley, Filip Sosenko, Janice Blenkinsopp, Sarah Johnsen, Mandy Littlewood, Gina Netto and Beth Watts found more than a million people across the UK are so impoverished they don’t have enough food, clothes, heating, shelter and toiletries. The report commissioned by UK charity the Joseph Rowntree Foundation was released on April 27, 2016 is based on a two years-long study. The report found: 1.25 million people, an agonizing figure, were destitute during 2015, 312,000 of whom were children. About 80 percent of these were born in Britain.

These people are humiliated and isolated. Persons considered destitute included those who:

[1] “had been forced to sleep rough”;

[2] “had no meal or just one per day over a period of 48 hours or longer”;

[3] “were unable to heat or light their home adequately for five or more days”; and

[4] “lacked weather-proof clothes or had to go without basic toiletries”.

A look at a randomly picked area provides further facts. The report on the garments sector in the India’s national capital region, cited above, says the following:

“[H]arsh, even sometimes violent, patterns of labour subordination in the industry are indisputable. In many countries, garment work could even be classified as ‘hazardous work’, based on the unsafe practices on which the industry seems to rely. Glaring examples of systemic malpractices in the sector, exposing workers to high degrees of danger and risk, have sadly emerged in the past three years across Asia.” (p. 38)

“It should be noted that the first disaster known in the history of garment production is the Triangle Shirtwaist factory fire, in New York City. It happened on March 25th 1911. Tellingly, over a hundred years apart, the NYC and South Asian cases reveal strikingly similar modalities. In all cases, evidence suggests that workers were locked into the factory premises. Recently, garment workers have been again subjected to high degrees of danger, risks and violence. In January 2014, the Cambodian government ordered its military and police to open fire on its own garment workers, who were on the street demanding an increase in minimum wages. These cases show how then informalisation of labour in the sector signifies much more than low wages and lack of benefits; it is effectively permeated by violence, and characterised by brutal patterns of disciplining, control, and subjugation of the workforce.” (pp. 38-9)

“Previous studies […] highlight the following employment trends at work in the NCR:

“1) The garment workforce is heavily composed of contract-workers […]

[…]

“3) A significant share of the garment workforce in the NCR is composed of homeworkers, due to high levels of value-addition in product cycles

“4) Both women and children work as homeworkers

“5) Homeworkers seem to be recruited and managed by contractors

“6) Overall, workers in both factories and homes are considered vulnerable as they are exposed to uncertain and casualised working conditions

“7) Unsurprisingly, levels of unionisation are extremely low

“8) So far, both national labour laws and corporate codes of conduct imposed by global buyers seem largely unable to improve working conditions.” (p. 41)

“Only six (1.7%) workers in our sample had written contracts. Most workers saw themselves as being casually employed (50.9 per cent) while 47.4 per cent saw themselves as being regularly employed (indefinite, oral contracts). Thus nearly half the workers see themselves as being in indefinite employment, although they do not have any contracts.” (p. 108)

“Work hours in the industry are long, particularly during peak periods, when they could be as high as 15 to 16 hours a day. […] 42.9 per cent of workers reported that their normal work hours were 6 to 9, while 50.9 per cent said that they worked between 10 and 12 hours and 6.2 per cent said that they worked an average of 13 to 16 hours per day. The highest work intensity is clearly in the large workshops, where 67.7 per cent of workers said that they worked for 10 to 12 hours and 29 per cent said that they worked for more than 13 hours a day.” (p. 120)

“Fifteen per cent of the workers in the sample say that they do not get breaks on public holidays and a similar percentage (14.2%) indicate that they do not get a weekly day-off while 15.6 per cent ― sometimes get a weekly day off.” (p. 126)

“[T]here is a thick haze of dust and particle pollution in some departments, especially in large factories. The main health risk undoubtedly comes from the nature of work – requiring focused attention and fixed postures, as well as long hours. Hours, as we have seen, are especially long in the workshops. Dust and particle pollution is regarded by workers as the main cause of health risk in the garment industry (i.e., by 79% of workers across all firms), followed by eye strain (39.1% of all workers). Accidents are regarded as a smaller but a significant source of health risk, with 7.9% of workers perceiving these to be the major health risk […]. In the workshop segment, however, eyestrain is seen as the biggest source of health risk, and the percentage of workers complaining of dust/particle pollution is highest in the export sector and in large enterprises.” (p. 128)

“No safety equipment is provided to workers in workshops but units in the factory sector do provide some equipment, mainly dust masks.” (p. 128)

“Exhaustion, eye strain, back pain and allergy are the most common occupational health problems mentioned by the workers”. (p. 129)

“Garment workers whom we have interviewed live in congested surroundings, often several workers to a room, which are located in urban and peri-urban villages and slums. The density of habitation in these localities is extraordinarily high and basic amenities are poor. Typically, land owners build tenements which are provided to workers on the basis of a monthly rent, and shared. Toilet and bathroom facilities are shared floor wise or across the building. Workers share these rooms with co-workers who could be related or unrelated.” (p. 143)

“The quality of housing for workers is also poor, with one-third of them describing the construction as semi-pukka and two-thirds describing the construction as pukka [brick/concrete made]. Access to toilets and bathrooms and to drinking water is crucial. But only 7.6 per cent of workers had access to a toilet attached to the room or inside the house. In all other cases, toilets and bathrooms were common in the building premises or workers used public toilets. Only 38.1 per cent of workers had access to tapped drinking water inside their premises while 33.6 per cent used a tap water facility located outside the premise and 23.2per cent used a handpump outside their premises. Another 5.2 per cent of workers mentioned other sources such as borewells.” (p. 145)

Do the human stories from the 21st century UK or India, sound different from the reality Engels found in 1844-’45 and, based on his findings, depicted in The Condition of the Working Class in England (1845) or far different from today’s toilers in Africa and Asia?

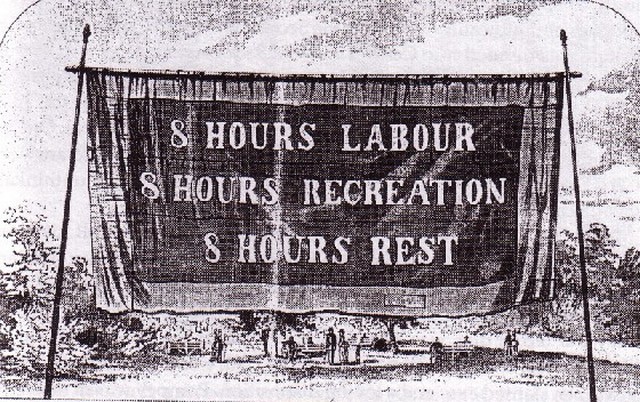

A contradictory reality emerges: higher profit or superprofit, and “deepening poverty, mass unemployment, social exclusion, greater inequality, and collective despair”, “rising insecurity, less choice, wage freezes”, “higher levels of work intensity”. Are not there relations or contradictions in the reality? Is there any reason that can make the reality in the underdeveloped hemisphere better than the European reality? Is the reality basically different from the reality that gave rise to the world workers’ May Day? In this May Day, the questions, basically old, demand renewed search.

Farooque Chowdhury, a Dhaka-based freelancer, has authored/edited three books in English (Micro Credit: Myth Manufactured (ed.), The Age of Crisis, and What Next? The Great Financial Crisis (ed.), and doesn’t operate any blog like “Farooque Chowdhury’s Blog”.

01 May, 2016

Countercurrents.org