By Ashish Singh

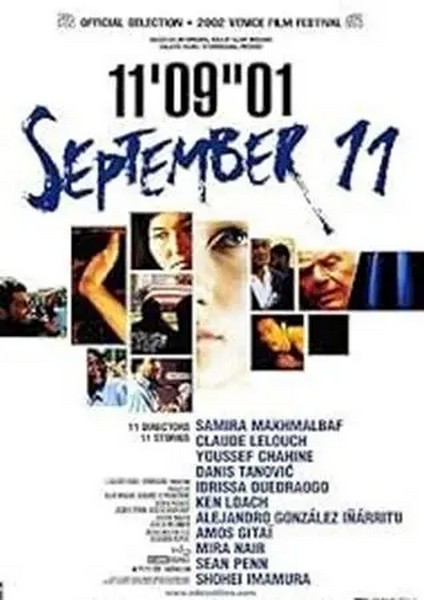

In the wake of the 9/11 attacks, filmmakers around the world turned their gaze not only toward New York, but also inward — toward their own histories of fear, violence, and grief. Among the most poignant responses came from two acclaimed directors: Israeli filmmaker Amos Gitai and Palestinian filmmaker Elia Suleiman. While Gitai contributed a segment to the 2002 international anthology 11’09″01 September 11, Suleiman created a separate, meditative response to the global moment of reckoning. These two films, emerging from different political realities and cinematic vocabularies, feel like echoes across a wall — distinct yet uncannily aligned.

Gitai’s short begins amid the chaos of a suicide bombing in Tel Aviv. Sirens wail, smoke rises, and a news team rushes to the scene, eager to broadcast the horror live. As reports begin to emerge about the attacks in New York, the Israeli anchor shrugs them off: “Why should we talk about that? We have our own terror here.” This blunt dismissal is not callousness, but a critique. Gitai holds up a mirror to national media narratives, asking whose suffering gets attention — and whose is always local, always somehow less urgent in the global conversation. His film is fast, chaotic, and relentless — a storm of sound and movement that forces us to confront how we weigh tragedy.

In contrast, Elia Suleiman’s response to 9/11 is wordless and slow, unfolding like a poem written in silences. Though not part of the 11’09″01 project, his 2002 film Divine Intervention was shaped in the shadows of the Twin Towers. Set in Ramallah and Jerusalem, it captures the surreal normalcy of occupation. Israeli tanks roll past houses. Soldiers stop cars and search passengers. A man peels an apple slowly. On a TV in the background, the world watches 9/11. But Suleiman — who appears in his own films as a silent observer — offers no commentary, only stillness. The violence is ever-present but quiet, embedded in the landscape. His cinema doesn’t shout; it watches.

These films never try to compete with the tragedy of 9/11. Neither Gitai nor Suleiman claims that their people’s suffering is greater, or more deserving of global grief. Instead, they offer something harder to process: the simultaneity of pain. They ask us to hold two truths in our minds — that while the world mourned New York, others lived in cities where explosions were routine, where the air always tasted faintly of smoke, and where grief did not begin on September 11.

Gitai’s urgency collides with Suleiman’s restraint. One film is built on speed, the other on stillness. But both arrive at the same insight — that violence is never localized. Its impact echoes across borders, across screens, across lives. When one city falls, others remember how often they have already been on fire.

Even decades later, these films remain painfully relevant. They ask what it means to be seen, and what it means to be forgotten. They challenge us not just to remember the towers that fell in New York, but to ask ourselves whose stories we never noticed collapsing in silence.

This is not just about history — it’s about empathy. Gitai and Suleiman, in radically different ways, show that true understanding begins when we stop ranking sorrow. When we look at each other’s tragedies not as interruptions to our own, but as part of a shared human condition. In a world where walls still rise and smoke still blurs our vision, these films offer one clear truth: every grief deserves to be seen.

Ashish Singh has finished his Ph.D. coursework in political science from the NRU-HSE, Moscow, Russia.

23 June 2025

Source: countercurrents.org