By Ashish Singh

In the sweltering Delhi summer of 2017, an unusual event slipped into the rhythm of urban life, not with the stiff collars of cultural protocol but with the ease of a sudden breeze in a closed room. Titled The Drifting Canvas, this immersive digital exhibition transformed Select City Walk Mall into a corridor of art history. Curated by Russian art historian Yasha Yavorskaya and brought to India by Vikas Nair and Manikantan, it was a quiet rebellion against elitism in the world of art.

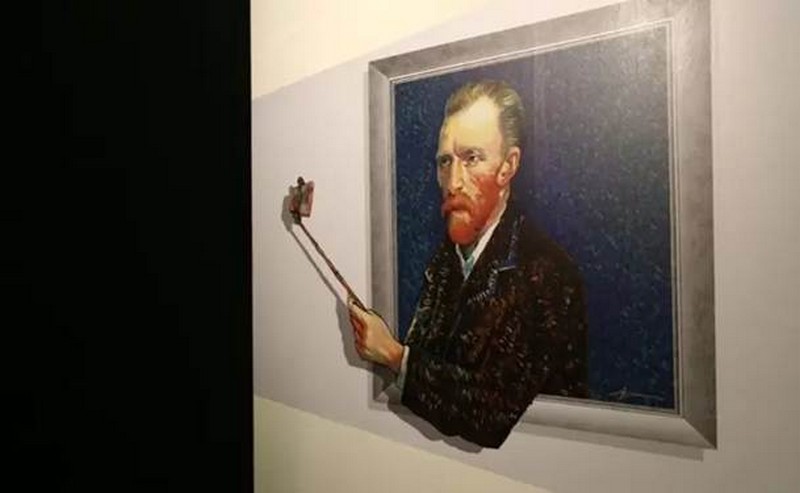

This wasn’t a gallery in the traditional sense. There were no guards shushing visitors, no hushed tones of reverence, no glass separating viewers from creation. Instead, over a thousand masterpieces from Van Gogh, Monet, Chagall, Schiele, Rousseau, and Malevich shimmered across massive HD screens, choreographed with music, motion, and light. Time itself seemed to stretch as brushstrokes unfolded slowly before the eyes. Children stood still. Shoppers paused. It was not spectacle for the sake of distraction. It was intervention. A reminder that beauty need not arrive with a price tag or pedigree.

But The Drifting Canvas was not merely a foreign showcase parachuted into an Indian mall. That temptation would have been easy and ultimately shallow. What grounded the exhibition meaningfully in India was the inclusion of Desi Canvas, a powerful countercurrent curated by Delhi-based artist Aakshat Sinha. With over 40 Indian artists ranging from the acclaimed Anupam Sud and Arpana Caur to emerging practitioners, Sinha’s section wasn’t supplementary. It was essential. It reminded viewers that India’s artistic language is not marginal but central, not reactive but assertive in its voice and vocabulary.

Sinha’s curatorial lens was sharp and unafraid. Works tackled caste, gender, myth, memory, violence, desire, and always the self. These weren’t the sanitized images of Indian art packaged for global validation. They were urgent, unsettling, and immediate. In dialogue with Western modernism, they did not defer. They responded.

This wasn’t just about visual pleasure. In a country where access to cultural spaces is still disproportionately urban, upper-class, and English-speaking, The Drifting Canvas quietly pushed back. It did what public institutions in India often fail to do. It created public art, not art in public spaces, but art for the public. When a child in South Delhi can encounter Egon Schiele’s raw emotion or Marc Chagall’s poetic surrealism on her way to the food court, that moment matters. And that’s the kind of cultural legitimacy we need to defend.

Of course, one might raise concerns. Are animated reproductions of masterworks truly art? Is there a danger of oversimplifying or commodifying aesthetics when you place them in a commercial mall? Possibly. But the alternative, hoarding art away from people in climate-controlled exclusivity, is far worse. When art is liberated from its curated silence and allowed to speak where life bustles and breathes, something genuinely democratic begins.

What The Drifting Canvas did was subtle but profound. It tore down the artificial boundary between connoisseur and casual observer. It said you didn’t need a degree in aesthetics to be moved by colour, form, or abstraction. You only needed to be there, to be present. It acknowledged that art, when made public, doesn’t lose its depth. It multiplies its meaning.

Manikantan, one of the key organisers, understood this intuitively. For him, this was not a one-time event but a possibility, a prototype for a different kind of cultural infrastructure, one where technology becomes the medium, not the barrier, for intimacy with art. Vikas Nair, equally invested, had first encountered the exhibition abroad and instinctively knew that India needed this not as indulgence but as a necessity.

Their intuition was right. The Drifting Canvas came at a time when art institutions in India were becoming increasingly insular and state support for creative expression was shrinking. Funding was precarious. Dissent was censored. And yet, here was a show that said art could still show up uninvited where no one expected it. And it could stay.

In many ways, Yasha’s decision to work with Indian collaborators rather than simply license a product was key. It allowed the exhibition to feel rooted even as it reached outward. The inclusion of Indian voices wasn’t decorative. It was dialogic.

Events like The Drifting Canvas remind us that art has the power to intervene in the most ordinary moments and render them unforgettable. They dissolve the outdated binary between the cultivated and the curious. They show us that wonder doesn’t discriminate and cultural legitimacy cannot remain the privilege of a few.

So perhaps it wasn’t just the canvas that drifted into the mall. It was memory, imagination, rebellion, and for a brief moment in Delhi, they all became public property.

Ashish Singh has finished his Ph.D. coursework in political science from the NRU-HSE, Moscow, Russia.

10 August 2025

Source: countercurrents.org