By Dr. Salim Nazzal

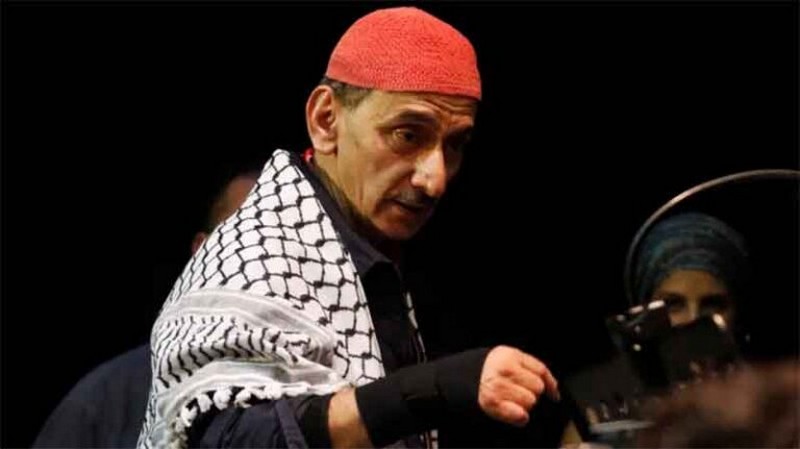

Losing Ziad Rahbani, for us the dreamers of the left in 1970s Beirut was not just the departure of a brilliant artist. It felt like a light going out, a light that had walked with us through the darkness. It was as if we had lost a friend whose soul we had known long before we shook his hand, a companion who walked the same streets, carried the same dream, and believed, as we did, that art could shake the pillars of this crumbling world.

Maybe I’m exaggerating or maybe not. Ziad didn’t belong to one generation or one movement, but we felt he was “one of us,” one of those who believed that a song could be a political manifesto, and that theater could be an arena of struggle, not just a luxury.

I remember him at the beginning of his journey, the day I saw him by chance at a café in Hamra alone, lost in his thoughts, as if traveling deep inside himself. My friend said, “That’s Ziad, Fairuz’s son.” We approached him, greeted him, and he responded with a faint smile.

Not long after, I attended his play Nazl Al-Sourour. I walked out of the hall feeling as though I had returned from a revolutionary voyage. I turned to the friend who was with me and said, with excitement: “This young man is a genius.” I don’t know where she is now life that brings people together also tears them apart. But if she reads these words, perhaps she will remember my awe that night, and how I spoke to her about it as if it were a prophecy.

That was just before the outbreak of the civil war, when Beirut was still Beirut the city of culture and beautiful noise. Around that time, I read The Mills of Beirut by Tawfiq Yusuf Awwad, a copy I had bought from the Lebanese University bookstore in UNESCO. And just like with Nazl Al-Sourour, I felt something cracking beneath the surface as if both the novel and the play were early warnings of the storm to come.

I lived then in Sin El Fil, in a small room with a garden, and we would spend our evenings listening to Joseph Sakr’s songs. I remember well when that same friend and I first listened to Al-Haleh Taabaneh Ya Layla, before Ziad himself would sing it later with his tender, angry voice. The voice, the lyrics, the melody all were a soft cry against everything.

During that period, the stage of Shoushou was thriving, and I would laugh with a heavy heart watching his plays. But my heart remained tied to Nazl Al-Sourour. Perhaps because it was about a group of friends dreaming of revolution and I was one of them. Not on stage, but in life. I was a dreamy communist, convinced that change was inevitable, and that Beirut could be reborn to the rhythm of songs, manifestos, and words.

But time is merciless. It slowly trimmed down our certainties. I later visited the Soviet Union, and that was the beginning of the fracture in my conviction. There, I started to piece myself back together. I never fully abandoned the dream, but I no longer saw it with the same innocence.

Still, Ziad remained a constant presence in my soul. I followed his works from A Long American Film to Bel Nesbeh La Bokra Shou. He remained, for me, that rare state of being on the edge: a rebel who didn’t raise slogans, an artist who didn’t compromise.

Ziad was defiance made music, rejection spoken in bittersweet satire. He lived through the era of great Arab defeats, yet tried to redefine the pulse of life. He wasn’t a preacher, but a lover of honest phrases, of melodies that said what newspapers could not.

And despite his communist background, he was never a prisoner of ideology. I saw him as naturally liberal free in spirit and thought, flitting between ideas like a bird that never settles in a cage, never repeating itself. That’s what made his art so expansive, so full of fresh rhythm.

As for his compositions for Fairuz they are collective memory. They’re not just music, but windows we open onto ourselves, onto days that weren’t perfect, but were real. They hold as much pain as they do longing, and just enough dream to help us endure what’s still to come.

Dr. Salim Nazzal is President of the European-Palestinian Cultural Forum

30 July 2025

Source: countercurrents.org