By Ed Vulliamy

Classified documents and research show that British, American and French governments were negotiating to cede ‘safe area’ town to Serbs

The fall of Srebrenica in Bosnia 20 years ago, prompting the worst massacre inEurope since the Third Reich, was a key element of the strategy pursued by the three key western powers –Britain, the US and France – and was not a shocking and unheralded event, as has long been maintained.

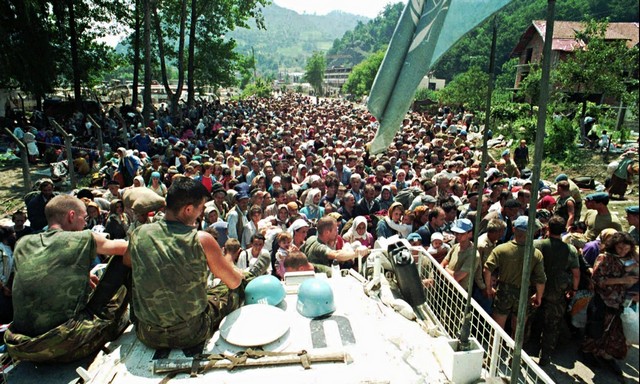

Eight thousand Bosnian Muslim men and boys were killed over four days in July 1995 by Bosnian Serb death squads after they took the besieged town, which had been designated a “safe area” under the protection of UN troops. The act has been declared a genocide by the war crimes tribunal in The Hague, and the Bosnian Serb leaders Radovan Karadžic and General Ratko Mladic await verdicts in trials for directing genocide.

Blame has also been placed on Dutch troops, who evicted thousands seeking refuge in their headquarters, and watched while the Serbs separated women and young children from their male quarry.

But a new investigation of the mass of evidence documenting the siege suggests much wider involvement in the events leading to the fall of Srebrenica. Declassified cables, exclusive interviews and testimony to the tribunal show that the British, American and French governments accepted – and sometimes argued – that Srebrenica and two other UN-protected safe areas were “untenable” long before Mladic took the town, and were ready to cede Srebrenica to the Serbs in pursuit of a map acceptable to the Serbian president, Slobodan Miloševic, for peace at any price.

But as they considered granting Srebrenica to the Serbs, western powers were also aware, or should have been, of the Bosnian Serb military “Directive 7” ordering the “permanent removal” of Bosnian Muslims from the safe areas. They also knew Mladic had told the Bosnian Serb assembly, “My concern is to have them vanish completely”, and that Karadžic pledged “blood up to the knees” if his army took Srebrenica.

Robert Frasure, a US diplomat working as an international representative, reported to Washington that Miloševic would not accept a peace map unless the safe areas were ceded to the Serbs. His boss, Anthony Lake, the US national security adviser, favoured a revised map that ceded Srebrenica, and the US policy-making Principals Committee urged that UN troops “pull back from vulnerable positions” – ergo, the safe areas.

France and Britain agreed, with UK defence secretary Sir Malcolm Rifkind arguing that the safe areas were “untenable”, as defended in 1995. As Mladic’s troops advanced on Srebrenica, the west failed to heed warnings of the town’s imminent fall. Once it had, says General Van der Wind of the Dutch defence ministry, in an exclusive interview with the Observer, the UN provided 30,000 litres of petrol, used by the Serbs to drive their quarry to the killing fields and plough their bodies into mass graves.

As the killing hit full throttle, top western negotiators met Mladic and Miloševic but did not raise the issue of mass murder, even though unclassified US cables show that the CIA was watching the killing fields almost “live” from satellite planes.

The shocking findings of high-level willingness in London, Washington and Paris to cede Srebrenica were collated over 15 years by Florence Hartmann, a former Le Monde correspondent, for a book, The Srebrenica Affair: The Blood of Realpolitik. Hartmann worked as a spokeswoman for the prosecutor at the international criminal tribunal for the former Yugoslavia between 2000 and 2006. Her previous book, Paix et Châtiment (Peace and Punishment), published in 2007, carried an account of a decision by the tribunal not to release crucial documents on the massacre to the Bosnian government in its unsuccessful attempt to sue Serbia for genocide at the international court of justice down the road in The Hague.

In August 2008, the tribunal indicted Hartmann for breach of confidentiality and summoned her for trial. In September 2009, she was convicted of contempt of court and fined €7,000. She deposited the fine in a French bank account, but the tribunal deemed the money unpaid and sentenced her to seven days’ imprisonment, ordering France to transfer her to The Hague. France refused.

Ed Vulliamy is a writer for the Guardian and Observer, and author of Amexica: War Along the Borderline

Saturday 4 July 201520.55 BSTLast modified on Sunday 5 July 2015