By Abdullah Al Ahsan

“On this day, 45 years ago, 93,000 members of Pakistani troops raised white flags and surrendered to Indian Army …,” wrote an Indian daily around this time two years ago. Indians celebrate December 16, 1971 as Vijay Diwas or victory day commemorating the event every year. For many reactionary caste-ridden Hindu nationalists this development came as a sweet revenge against almost thousand years of Muslim rule. Why these Hindu nationalists are are so Islamophobic? This phenomenon demands some reflections in the wider context of history.

The main challenge for these Hindu nationalists is history itself. History bears witness that Ikhtiar Uddin Muhammad Bakhtiar Khilji (d. 1206), a Turkish general, had spread political Islam in Bengal in 1203/4 with the help of only 18 horse-riders. The original author of the Indian national song Vanda Mataram, Bankim C Chatterjee, claimed that only a black sheep or an outcast could believe in such a claim. Unfortunately, these Islamophobic elements do not like to examine history properly. One must note that Islam was already known to the people of Bengal through traders and Sufis and there was a demand from the local population for political Islam. Islamophobics also ignore the fact that just next to India, throughout Southeast Asia, no Islamic political conquest occurred and yet the whole area hosts one of the highest concentrations of Muslims in the world today. One should also note that although liberal Hindu historians such as Jawaharlal Nehru or Shashi Throor recorded the economic prosperity that India had achieved under Muslim rule and how the British East India Company (EIC) destroyed the economy of Bengal, they hardly offer any credit to Muslim rulers of Bengal for their achievements. That is why one must evaluate the so-called Vijay Diwas in light of such Islamophobic mindset.

Indian nationalists clearly did not want Pakistan to come into existence. They wanted to see Pakistan collapse immediately. India subjugated the people of Kashmir, Hyderabad and Junagarh and imposed war in Kashmir. India also refused to deliver Pakistan’s due share funds from the central government budget and military hardware. Pakistan did not inherit any seat for its central government. Yet Pakistan survived almost miraculously. However, Pakistan became victim of its own burden for which it must conduct self-assessment. It has paid a very high price in 1971. Some references to the role of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, leader of what he called Naya or new Pakistan, will illustrate this point.

For any self-assessment, one must first admit that something has gone wrong and that there is a need for evaluating a given situation. However, this has not happened in Pakistan. Immediately after the election 1970 an arrogant Bhutto began to create obstacles for a peaceful political transition. He literally threatened the newly elected West Pakistani members of the parliament that if they had gone to East Pakistan to attend any session, their legs would be amputated. He then joined in a conspiracy with some military and civilian bureaucrats to crackdown on East Pakistanis who were genuinely demanding their legitimate rights. But military cracked down and Pakistan armed forces were accused of killing millions, raping hundreds and thousands and committing genocide. The new administration deliberately covered up the report of its own investigation on the subject. The containment was necessary because it found Mr. Bhutto was greatly responsible for the dismemberment of Pakistan. Pakistan’s refusal to take a stand on the allegations implied an acceptance of those claims. Almost half a century has passed since the event and although the event haunts many Pakistani psyches, the propaganda rhetoric against Pakistan has not been directly challenged. On this day Pakistan must revisit history and find out what went wrong.

Unfinished Battle of Faith or Stolen Victory

I have recently received two books related to the subject for review. The first one is The Political History of Muslim Bengal: An Unfinished Battle of Faith (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2019) by Mr. Mahmudur Rahman, editor of the popular Bangladeshi daily Amar Desh; and the other The Stolen Victory by Brig Sultan Ahmed, a Pakistani officer who served in East Pakistan in 1971. The last book was originally published in 1996 but has been re-published in 2018. Brig Sultan’s heroic resistance against the advancing Indian armed forces has been well-recognized both by Indians and international observers. He notes that, “India stole victory from Pakistan … Armed forces begged for battle … they were prepared to offer sacrifice of their lives to save the integrity and honour of their country. Their commanders, however, whose weak wills had been conquered, abjectly and ignominiously, surrendered (p.82).” His commander was rather interested in rewarding his “men, who ought to be given gallantry awards,” he reports (p.233).

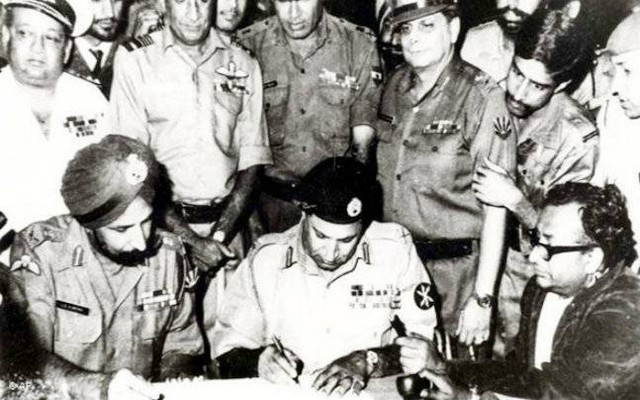

Although many Bangladeshis celebrate December 16 as Bijoy Dibos or Victory Day, Editor Mahmudur Rahman seems to have a mixed feeling about the occasion. Reporting about the Pakistan army’s surrender document, he says, “No signature from the Bangladeshi representative was felt necessary by the Indian command (p. 168).” He also notes that, “The day of December 1971 is the most glorious in the history of post-1947 India as the dream of Nehru and Patel to divide Pakistan was fulfilled (p. 170).” Rahman also notes that, “President Yahya would later foolishly fall into the Indian trap by declaring war against India on 3 December 1971 at the height of Indian preparedness (pp 153-4).” He also records that, “Just one day before Niazi’s surrender, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto surprisingly torpedoed the last chance for a face-saving withdrawal of the beleaguered Pakistani forces from Dhaka by rejecting a Polish proposal at the United Nations. Whether it was a deliberate act to complete the humiliation of arrogant armed forces of Pakistan, or sheer madness on the part of the head of the Pakistani delegation at UN remains unanswered (p. 169).” These are very penetrating observations for reflections on the significance of the day.

Rahman continues with his description of what he calls, “unfinished battle of faith.” In independent Bangladesh resumed a struggle for self-assertion of Muslim Bengal, which one perhaps may call – the shaping of Bangladeshi nationalism. This was happening mainly as opposed to an imposition of Indian hegemony immediately after the war in 1971. India wanted to see a Bhutan or Sikkim in Bangladesh. One event is particularly noteworthy in this context. On February 25, 2009 a segment of Bangladesh’s armed forces revolted and Rahman reports, “It had been an orgy of slaughter and rape. Fifty-seven officers, from major generals to lieutenants, had been murdered in cold blood (307).” The UK based Telegraph reported that “Bangladeshi army officers blame prime minister for mutiny.” It should be noted that in 1971, during the nine-month long war, Bengalis didn’t lose so many officers. The message to the armed forces was loud and clear: armed forces must be subservient to hegemonic power. Bangladesh army has witnessed many coups and counter coups since 1975, and must now be very careful about any such attempt in the future. Indian hegemony had now stood at a much firmer grounds. Since 2009 Bangladesh has turned into another vassal state along with Bhutan and Sikkim in the Indian neighbourhood.

According to Mahmudur Rahman, assertion of Muslim identity of Bengal would be essential to regain dignity of Bangladesh. But why Muslim Bengal? Doesn’t it sound communal? These questions demand some reference to history of Bengal. When the EIC occupied Bengal in 1757, it was Muslim Bengal, ruled under the prescriptions of Shari’ah. The land was economically very prosperous which had ensured participation of all communities in its prosperity. Adam Smith in 1776 recognized the importance of trade between Bengal and London. In order to consolidate power, the EIC established Calcutta Madrasah in 1781, Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal in 1784 which paved the way to colonial educational policy and what one may call Orientalism. Many British liberals such as Lord Macaulay, John Mill, James Mill, and the academic William Muir all worked for the EIC. The EIC literally crushed the local aristocracy and encouraged what came to be known as Bengal renaissance creating mostly a new Hindu landlord class. Both authors of the Indian national song, mentioned above, were products of this development. Britain’s Bengal experiment became model for colonial control in the 19th century. One must understand the demand for the restoration of Muslim Bengal in this context.

The Muslim Bengal concept explains why Bengalis not only demanded but became the backbone for the Pakistan demand. When the All India Muslim League, political party that led the Pakistan movement, was founded in 1906 Mr. Jinnah was invited to participate. But he rejected the idea calling it communal. However, with the passage of time his experience working with the so called Indian liberals changed his perception and he found solution to India’s problem in the Islamic worldview. The idea of Pakistan, of course, came from the poet-philosopher Muhammad Iqbal who wanted to see an independent India with equal rights and dignity for all. But he too was disappointed with the attitude of self-styled liberals such as MK Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru. Iqbal was also aware of the social Darwinist stricken Europe and found solution to the problem of humanity in his Pakistan demand. I find striking similarity between Mahmudur Rahman’s Muslim Bengal and Iqbal’s Pakistan idea.

Paigham-e-Pakistan

During my last visit to Pakistan about a month ago I was given a book entitled Paigham-e-Pakistan to review. This book has been published to counter the rise of extremist ideas in Pakistan in recent years. I thought the message of the book was timely, particularly following the last general election. In my view Imran Khan’s model state of Madinah is no different from Paigham-e-Pakistan envisioned by the poet Iqbal. I also find striking similarity between Iqbal’s vision and the demand for the restoration of Muslim Bengali identity.

Now, returning to the significance of December 16 – whether the day is a victory day or a day of disgrace – it all depends on where one stands. For someone who values human dignity and lessons from history, this day can’t be a victory day. This is particularly true in the context of the current situation in Bangladesh where the ruling party seems to have taken contract from India to impose Indian hegemony on the nation. In this struggle for self-assertion Bangladeshis need Pakistan’s support. However, Pakistan needs to come forward for its own sake. One must recognize with admiration Imran Khan’s citizenship offer to Bengalis living in Pakistan. This is the first government in Pakistan since 1971 which seems to recognize the importance of looking at its history rationally. On this day Pakistan should go further and recognize Bengal’s contributions to the Pakistan movement. History bears the witness that without Bengal’s contribution, Pakistan could not have been achieved. Pakistan should apologize for Bhutto’s arrogant behaviour and armed forces’ crackdown in 1971. This apology will have the potential to restore Pakistan’s own dignity. It will pave the way from disgrace to dignity.

Dr.Abdullah Al Ahsan is a member of the International Movement for a Just World (JUST).

19 December 2018