By Nafeez Mosaddeq Ahmed

Why France’s brave new war on ISIS is a sick joke and an insult to the victims of the Paris attacks.

“We stand alongside Turkey in its efforts in protecting its national security and fighting against terrorism. France and Turkey are on the same side within the framework of the international coalition against the terrorist group ISIS.”

— Statement by French Foreign Ministry, July 2015

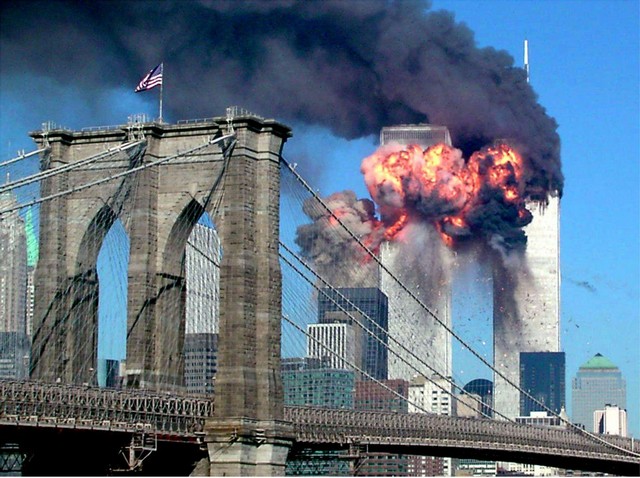

19 Nov 2015 – The 13th November Paris massacre will be remembered, like 9/11, as a defining moment in world history.

The murder of 129 people, the injury of 352 more, by ‘Islamic State’ (ISIS) acolytes striking multiple targets simultaneously in the heart of Europe, mark a major sea-change in the terror threat.

For the first time, a Mumbai-style attack has occurred on Western soil — the worst attack on Europe in decades. As such, it has triggered a seemingly commensurate response from France: the declaration of a nationwide state of emergency, the likes of which have not been seen since the 1961 Algerian war.

ISIS has followed up with threats to attack Washington and New York City.

Meanwhile, President Hollande wants European Union leaders to suspend the Schengen Agreement on open borders to allow dramatic restrictions on freedom of movement across Europe. He also demands the EU-wide adoption of the Passenger Name Records (PNR) system allowing intelligence services to meticulously track the travel patterns of Europeans, along with an extension of the state of emergency to at least three months.

Under the extension, French police can now block any website, put people under house arrest without trial, search homes without a warrant, and prevent suspects from meeting others deemed a threat.

“We know that more attacks are being prepared, not just against France but also against other European countries,” said the French Prime Minister Manuel Valls. “We are going to live with this terrorist threat for a long time.”

Hollande plans to strengthen the powers of police and security services under new anti-terror legislation, and to pursue amendments to the constitution that would permanently enshrine the state of emergency into French politics. “We need an appropriate tool we can use without having to resort to the state of emergency,” he explained.

Parallel with martial law at home, Hollande was quick to accelerate military action abroad, launching 30 airstrikes on over a dozen Islamic State targets in its de facto capital, Raqqa.

France’s defiant promise, according to Hollande, is to “destroy” ISIS.

The ripple effect from the attacks in terms of the impact on Western societies is likely to be permanent. In much the same way that 9/11 saw the birth of a new era of perpetual war in the Muslim world, the 13/11 Paris attacks are already giving rise to a brave new phase in that perpetual war: a new age of Constant Vigilance, in which citizens are vital accessories to the police state, enacted in the name of defending a democracy eroded by the very act of defending it through Constant Vigilance.

Mass surveillance at home and endless military projection abroad are the twin sides of the same coin of national security, which must simply be maximized as much as possible.

“France is at war,” Hollande told French parliament at the Palace of Versailles.

“We’re not engaged in a war of civilizations, because these assassins do not represent any. We are in a war against jihadist terrorism which is threatening the whole world.”

The friend of our enemy is our friend

Conspicuously missing from President Hollande’s decisive declaration of war however, was any mention of the biggest elephant in the room: state-sponsorship.

Syrian passports discovered near the bodies of two of the suspected Paris attackers, according to police sources, were fake, and likely forged in Turkey.

Earlier this year, the Turkish daily Meydan reported that citing an Uighur source that more than 100,000 fake Turkish passports had been given to ISIS. The figure, according to the US Army’s Foreign Studies Military Office (FSMO), is likely exaggerated, but corroborated “by Uighurs captured with Turkish passports in Thailand and Malaysia.”

Further corroboration came from a Sky News Arabia report by correspondent Stuart Ramsey, which revealed that the Turkish government was certifying passports of foreign militants crossing the Turkey-Syria border to join ISIS. The passports, obtained from Kurdish fighters, had the official exit stamp of Turkish border control, indicating the ISIS militants had entered Syria with full knowledge of Turkish authorities.

The dilemma facing the Erdogan administration is summed up by the FSMO: “If the country cracks down on illegal passports and militants transiting the country, the militants may target Turkey for attack. However, if Turkey allows the current course to continue, its diplomatic relations with other countries and internal political situation will sour.”

This barely scratches the surface. A senior Western official familiar with a large cache of intelligence obtained this summer from a major raid on an ISIS safehouse told the Guardian that “direct dealings between Turkish officials and ranking ISIS members was now ‘undeniable.’”

The same official confirmed that Turkey, a longstanding member of NATO, is not just supporting ISIS, but also other jihadist groups, including Ahrar al-Sham and Jabhat al-Nusra, al-Qaeda’s affiliate in Syria. “The distinctions they draw [with other opposition groups] are thin indeed,” said the official. “There is no doubt at all that they militarily cooperate with both.”

In a rare insight into this brazen state-sponsorship of ISIS, a year ago Newsweek reported the testimony of a former ISIS communications technician, who had travelled to Syria to fight the regime of Bashir al-Assad.

The former ISIS fighter told Newsweek that Turkey was allowing ISIS trucks from Raqqa to cross the “border, through Turkey and then back across the border to attack Syrian Kurds in the city of Serekaniye in northern Syria in February.” ISIS militants would freely travel “through Turkey in a convoy of trucks,” and stop “at safehouses along the way.”

The former ISIS communication technician also admitted that he would routinely “connect ISIS field captains and commanders from Syria with people in Turkey on innumerable occasions,” adding that “the people they talked to were Turkish officials… ISIS commanders told us to fear nothing at all because there was full cooperation with the Turks.”

In January, authenticated official documents of the Turkish military were leaked online, showing that Turkey’s intelligence services had been caught in Adana by military officers transporting missiles, mortars and anti-aircraft ammunition via truck “to the al-Qaeda terror organisation” in Syria.

According to other ISIS suspects facing trial in Turkey, the Turkish national military intelligence organization (MIT) had begun smuggling arms, including NATO weapons to jihadist groups in Syria as early as 2011.

The allegations have been corroborated by a prosecutor and court testimony of Turkish military police officers, who confirmed that Turkish intelligence was delivering arms to Syrian jihadists from 2013 to 2014.

Documents leaked in September 2014 showed that Saudi Prince Bandar bin Sultan had financed weapons shipments to ISIS through Turkey. A clandestine plane from Germany delivered arms in the Etimesgut airport in Turkey and split into three containers, two of which were dispatched to ISIS.

A report by the Turkish Statistics Institute confirmed that the government had provided at least $1 million in arms to Syrian rebels within that period, contradicting official denials. Weapons included grenades, heavy artillery, anti-aircraft guns, firearms, ammunition, hunting rifles and other weapons — but the Institute declined to identify the specific groups receiving the shipments.

Information of that nature emerged separately. Just two months ago, Turkish police raided a news outlet that published revelations on how the local customs director had approved weapons shipments from Turkey to ISIS.

Turkey has also played a key role in facilitating the life-blood of ISIS’ expansion: black market oil sales. Senior political and intelligence sources in Turkey and Iraq confirm that Turkish authorities have actively facilitated ISIS oil sales through the country.

Last summer, Mehmet Ali Ediboglu, an MP from the main opposition, the Republican People’s Party, estimated the quantity of ISIS oil sales in Turkey at about $800 million — that was over a year ago.

By now, this implies that Turkey has facilitated over $1 billion worth of black market ISIS oil sales to date.

There is no “self-sustaining economy” for ISIS, contrary to the fantasies of the Washington Post and Financial Times in their recent faux investigations, according to Martin Chulov of the Guardian:

“… tankers carrying crude drawn from makeshift refineries still make it to the [Turkey-Syria] border. One Isis member says the organisation remains a long way from establishing a self-sustaining economy across the area of Syria and Iraq it controls. ‘They need the Turks. I know of a lot of cooperation and it scares me,’ he said. ‘I don’t see how Turkey can attack the organisation too hard. There are shared interests.’”

Senior officials of the ruling AKP have conceded the extent of the government’s support for ISIS.

The liberal Turkish daily Taraf quoted an AKP founder, Dengir Mir Mehmet Fırat, admitting: “In order to weaken the developments in Rojova [Kurdish province in Syria] the government gave concessions and arms to extreme religious groups…the government was helping the wounded. The Minister of Health said something such as, it’s a human obligation to care for the ISIS wounded.”

The paper also reported that ISIS militants routinely receive medical treatment in hospitals in southeast Turkey— including al-Baghdadi’s right-hand man.

Writing in Hurriyet Daily News, journalist Ahu Ozyurt described his “shock” at learning of the pro-ISIS “feelings of the AKP’s heavyweights” in Ankara and beyond, including “words of admiration for ISIL from some high-level civil servants even in Şanliurfa. ‘They are like us, fighting against seven great powers in the War of Independence,’ one said. ‘Rather than the PKK on the other side, I would rather have ISIL as a neighbor,’ said another.”

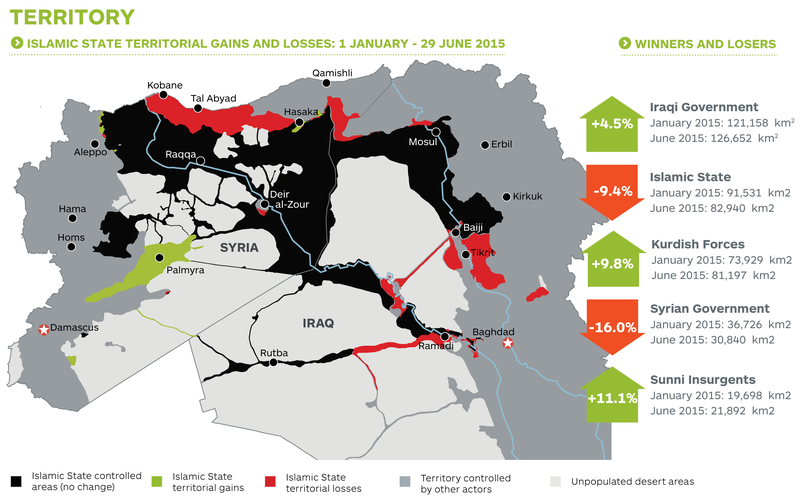

Meanwhile, NATO leaders feign outrage and learned liberal pundits continue to scratch their heads in bewilderment as to ISIS’ extraordinary resilience and inexorable expansion.

Unsurprisingly, then, Turkey’s anti-ISIS bombing raids have largely been token gestures. Under cover of fighting ISIS, Turkey has largely used the opportunity to bomb the Kurdish forces of the Democratic Union Party (YPG) in Syria and Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) in Turkey and Iraq. Yet those forces are widely recognized to be the most effective fighting ISIS on the ground.

Meanwhile, Turkey has gone to pains to thwart almost every US effort to counter ISIS. When this summer, 54 graduates of the Pentagon’s $500 million ‘moderate’ Syrian rebel train-and-equip program were kidnapped by Jabhat al-Nusra — al-Qaeda’s arm in Syria — it was due to a tip-off from Turkish intelligence.

The Turkish double-game was confirmed by multiple rebel sources to McClatchy, but denied by a Pentagon spokesman who said, reassuringly:

“Turkey is a NATO ally, close friend of the United States and an important partner in the international coalition.”

Nevermind that Turkey has facilitated about $1 billion in ISIS oil sales.

According to a US-trained Division 30 officer with access to information on the incident, Turkey was trying “to leverage the incident into an expanded role in the north for the Islamists in Nusra and Ahrar” and to persuade the United States to “speed up the training of rebels.”

As Professor David Graeber of London School of Economics pointed out:

“Had Turkey placed the same kind of absolute blockade on Isis territories as they did on Kurdish-held parts of Syria… that blood-stained ‘caliphate’ would long since have collapsed — and arguably, the Paris attacks may never have happened. And if Turkey were to do the same today, Isis would probably collapse in a matter of months. Yet, has a single western leader called on Erdoğan to do this?”

Some officials have spoken up about the paradox, but to no avail. Last year, Claudia Roth, deputy speaker of the German parliament, expressed shock that NATO is allowing Turkey to harbour an ISIS camp in Istanbul, facilitate weapons transfers to Islamist militants through its borders, and tacitly support IS oil sales.

Nothing happened.

Instead, Turkey has been amply rewarded for its alliance with the very same terror-state that wrought the Paris massacre on 13th November 2015. Just a month earlier, German Chancellor Angela Merkel offered to fast-track Turkey’s bid to join the EU, permitting visa-free travel to Europe for Turks.

No doubt this would be great news for the security of Europe’s borders.

State-sponsorship

It is not just Turkey. Senior political and intelligence sources in the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) have confirmed the complicity of high-level KRG officials in facilitating ISIS oil sales, for personal profit, and to sustain the government’s flagging revenues.

Despite a formal parliamentary inquiry corroborating the allegations, there have been no arrests, no charges, no prosecutions.

The KRG “middle-men” and other government officials facilitating these sales continue their activities unimpeded.

In his testimony before the Senate Armed Services Committee in September 2014, General Martin Dempsey, then chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, was asked by Senator Lindsay Graham whether he knew of “any major Arab ally that embraces ISIL”?

General Dempsey replied:

“I know major Arab allies who fund them.”

In other words, the most senior US military official at the time had confirmed that ISIS was being funded by the very same “major Arab allies” that had just joined the US-led anti-ISIS coalition.

These allies include Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the UAE, and Kuwait in particular — which for the last four years at least have funneled billions of dollars largely to extremist rebels in Syria. No wonder that their anti-ISIS airstrikes, already miniscule, have now reduced almost to zero as they focus instead on bombing Shi’a Houthis in Yemen, which, incidentally, is paving the way for the rise of ISIS there.

Porous links between some Free Syrian Army (FSA) rebels, Islamist militant groups like al-Nusra, Ahrar al-Sham and ISIS, have enabled prolific weapons transfers from ‘moderate’ to Islamist militants.

The consistent transfers of CIA-Gulf-Turkish arms supplies to ISIS have been documented through analysis of weapons serial numbers by the UK-based Conflict Armament Research (CAR), whose database on the illicit weapons trade is funded by the EU and Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs.

“Islamic State forces have captured significant quantities of US-manufactured small arms and have employed them on the battlefield,” a CAR report found in September 2014. “M79 90 mm anti-tank rockets captured from IS forces in Syria are identical to M79 rockets transferred by Saudi Arabia to forces operating under the ‘Free Syrian Army’ umbrella in 2013.”

German journalist Jurgen Todenhofer, who spent 10 days inside the Islamic State, reported last year that ISIS is being “indirectly” armed by the West:

“They buy the weapons that we give to the Free Syrian Army, so they get Western weapons — they get French weapons… I saw German weapons, I saw American weapons.”

ISIS, in other words, is state-sponsored — indeed, sponsored by purportedly Western-friendly regimes in the Muslim world, who are integral to the anti-ISIS coalition.

Which then begs the question as to why Hollande and other Western leaders expressing their determination to “destroy” ISIS using all means necessary, would prefer to avoid the most significant factor of all: the material infrastructure of ISIS’ emergence in the context of ongoing Gulf and Turkish state support for Islamist militancy in the region.

There are many explanations, but one perhaps stands out: the West’s abject dependence on terror-toting Muslim regimes, largely to maintain access to Middle East, Mediterranean and Central Asian oil and gas resources.

Pipelines

Much of the strategy currently at play was candidly described in a 2008 US Army-funded RAND report, Unfolding the Future of the Long War (pdf). The report noted that “the economies of the industrialized states will continue to rely heavily on oil, thus making it a strategically important resource.” As most oil will be produced in the Middle East, the US has “motive for maintaining stability in and good relations with Middle Eastern states.” It just so happens that those states support Islamist terrorism:

“The geographic area of proven oil reserves coincides with the power base of much of the Salafi-jihadist network. This creates a linkage between oil supplies and the long war that is not easily broken or simply characterized… For the foreseeable future, world oil production growth and total output will be dominated by Persian Gulf resources… The region will therefore remain a strategic priority, and this priority will interact strongly with that of prosecuting the long war.”

Declassified government documents clarify beyond all doubt that a primary motivation for the 2003 Iraq War, preparations for which had begun straight after 9/11, was installing a permanent US military presence in the Persian Gulf to secure access to the region’s oil and gas.

The obsession over black gold did not end with Iraq, though — and is not exclusive to the West.

“Most of the foreign belligerents in the war in Syria are gas-exporting countries with interests in one of the two competing pipeline projects that seek to cross Syrian territory to deliver either Qatari or Iranian gas to Europe,” wrote Professor Mitchell Orenstein of the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies at Harvard University, in Foreign Affairs, the journal of Washington DC’s Council on Foreign Relations.

In 2009, Qatar had proposed to build a pipeline to send its gas northwest via Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Syria to Turkey. But Assad “refused to sign the plan,” reports Orenstein. “Russia, which did not want to see its position in European gas markets undermined, put him under intense pressure not to.”

Russia’s Gazprom sells 80% of its gas to Europe. So in 2010, Russia put its weight behind “an alternative Iran-Iraq-Syria pipeline that would pump Iranian gas from the same field out via Syrian ports such as Latakia and under the Mediterranean.” The project would allow Moscow “to control gas imports to Europe from Iran, the Caspian Sea region, and Central Asia.”

Then in July 2011, a $10 billion Iran-Iraq-Syria pipeline deal was announced, and a preliminary agreement duly signed by Assad.

Later that year, the US, UK, France and Israel were ramping up covert assistance to rebel factions in Syria to elicit the “collapse” of Assad’s regime “from within.”

“The United States… supports the Qatari pipeline as a way to balance Iran and diversify Europe’s gas supplies away from Russia,” explained Orenstein in Foreign Affairs.

An article in the Armed Forces Journal published last year by Major Rob Taylor, an instructor at the US Army’s Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, thus offered scathing criticism of conventional media accounts of the Syrian conflict that ignore the pipeline question:

“Any review of the current conflict in Syria that neglects the geopolitical economics of the region is incomplete… Viewed through a geopolitical and economic lens, the conflict in Syria is not a civil war, but the result of larger international players positioning themselves on the geopolitical chessboard in preparation for the opening of the pipeline… Assad’s pipeline decision, which could seal the natural gas advantage for the three Shi’a states, also demonstrates Russia’s links to Syrian petroleum and the region through Assad. Saudi Arabia and Qatar, as well as al-Qaeda and other groups, are maneuvering to depose Assad and capitalize on their hoped-for Sunni conquest in Damascus. By doing this, they hope to gain a share of control over the ‘new’ Syrian government, and a share in the pipeline wealth.”

The pipelines would access not just gas in the Iran-Qatari field, but also potentially newly discovered offshore gas resources in the Eastern Mediterranean — encompassing the offshore territories of Israel, Palestine, Cyprus, Turkey, Egypt, Syria, and Lebanon. The area has been estimated to hold as much as 1.7 billion barrels of oil and up to 122 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, which geologists believe could be just a third of the total quantities of undiscovered fossil fuels in the Levant.

A December 2014 report by the US Army War College’s Strategic Studies Institute, authored by a former UK Ministry of Defense research director, noted that Syria specifically holds significant offshore oil and gas potential. It noted:

“Once the Syria conflict is resolved, prospects for Syrian offshore production — provided commercial resources are found — are high.”

Assad’s brutality and illegitimacy is beyond question — but until he had demonstrated his unwillingness to break with Russia and Iran, especially over their proposed pipeline project, US policy toward Assad had been ambivalent.

State Department cables obtained by Wikileaks reveal that US policy had wavered between financing Syrian opposition groups to facilitate “regime change,” and using the threat of regime change to induce “behavior reform.”

President Obama’s preference for the latter resulted in US officials, including John Kerry, shamelessly courting Assad in the hopes of prying him away from Iran, opening up the Syrian economy to US investors, and aligning the regime with US-Israeli regional designs.

Even when the 2011 Arab Spring protests resulted in Assad’s security forces brutalizing peaceful civilian demonstrators, both Kerry and then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton insisted that he was a “reformer” — which he took as a green light to respond to further protests with massacres.

Assad’s decision to side with Russia and Iran, and his endorsement of their favoured pipeline project, were key factors in the US decision to move against him.

Europe’s dance with the devil

Turkey plays a key role in the US-Qatar-Saudi backed route designed to circumvent Russia and Iran, as an intended gas hub for exports to European markets.

It is only one of many potential pipeline routes involving Turkey.

“Turkey is key to gas supply diversification of the entire European Union. It would be a huge mistake to stall energy cooperation any further,” urged David Koranyi, director of the Atlantic Council’s Eurasian Energy Futures initiative and a former national security advisor to the Prime Minister of Hungary.

Koranyi noted that both recent “major gas discoveries in the Eastern Mediterranean” and “gas supplies from Northern Iraq” could be “sourced to supply the Turkish market and transported beyond to Europe.”

Given Europe’s dependence on Russia for about a quarter of its gas, the imperative to minimize this dependence and reduce the EU’s vulnerability to supply outages has become an urgent strategic priority. The priority fits into longstanding efforts by the US to wean Central and Eastern Europe out of the orbit of Russian power.

Turkey is pivotal to the US-EU vision for a new energy map:

“The EU would gain a reliable alternative supply route to further diversify its imports from Russia. Turkey, as a hub, would benefit from transit fees and other energy-generated revenues. As additional supplies of gas may become available for export over the next five to 10 years in the wider region, Turkey is the natural route via which these could be shipped to Europe.”

A report last year by Anglia Ruskin University’s Global Sustainability Institute (GSI) warned that Europe faced a looming energy crisis, particularly the UK, France and Italy, due to “critical shortages of natural resources.”

“Coal, oil and gas resources in Europe are running down and we need alternatives,” said GSI’s Professor Victoria Andersen.

She also recommended a rapid shift to renewables, but most European leaders apparently have other ideas — namely, shifting to a network of pipelines that would transport oil and gas from the Middle East, Eastern Mediterranean and Central Asia to Europe: via our loving friend, Erdogan’s Turkey.

Nevermind that under Erdogan, Turkey is the leading sponsor of the barbaric ‘Islamic State.’

We must not ask unpatriotic questions about Western foreign policy, or NATO for that matter.

We must not wonder about the pointless spectacle of airstrikes and Stazi-like police powers, given our shameless affair with Erdogan’s terror-regime, which funds and arms our very own enemy.

We must not question the motives of our elected leaders, who despite sitting on this information for years, still lie to us, flagrantly, even now, before the blood of 129 French citizens has even dried, pretending that they intend to “destroy” a band of psychopathic murdering scum, armed and funded from within the heart of NATO.

No, no, no. Life goes on. Business-as-usual must continue. Citizens must keep faith in the wisdom of The Security State.

The US must insist on relying on Turkish intelligence to vet and train ‘moderate’ rebels in Syria, and the EU must insist on extensive counter-terrorism cooperation with Erdogan’s regime, while fast-tracking the ISIS godfather’s accession into the union.

But fear not: Hollande is still intent on “destroying” ISIS. Just like Obama and Cameron — and Erdogan.

It’s just that some red lines simply cannot be crossed.

Nafeez Mosaddeq Ahmed, Ph.D. is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace, Development and Environment and founder, editor-in-chief of INSURGE intelligence. He is an investigative journalist, bestselling author and international security scholar. He is the winner of a 2015 Project Censored Award, known as the ‘Alternative Pulitzer Prize’, for Outstanding Investigative Journalism for his Guardian work, and was selected in the Evening Standard’s ‘Power 1,000’ most globally influential Londoners. Nafeez has also written for TRANSCEND Media Service, The Independent, Sydney Morning Herald, The Age, The Scotsman, Foreign Policy, The Atlantic, Quartz, Prospect, New Statesman, Le Monde Diplomatique, New Internationalist, Counterpunch, Truthout, among others. He is a Visiting Research Fellow at the Faculty of Science and Technology at Anglia Ruskin University. He is the author of A User’s Guide to the Crisis of Civilization: And How to Save It (2010), and the scifi thriller novel Zero Point, among other books. His work on the root causes and covert operations linked to international terrorism officially contributed to the 9/11 Commission and the 7/7 Coroner’s Inquest.

This article was amended on 21st November 2015 to review and supplement sources cited relating to Turkish sponsorship of ISIS, ensuring their credibility, accuracy and plausibility. Some previously quoted sources were removed due to being too partisan within the Turkish political scene, and new more reliable sources added.

23 November 2015

www.transcend.org