By Tunç Türel

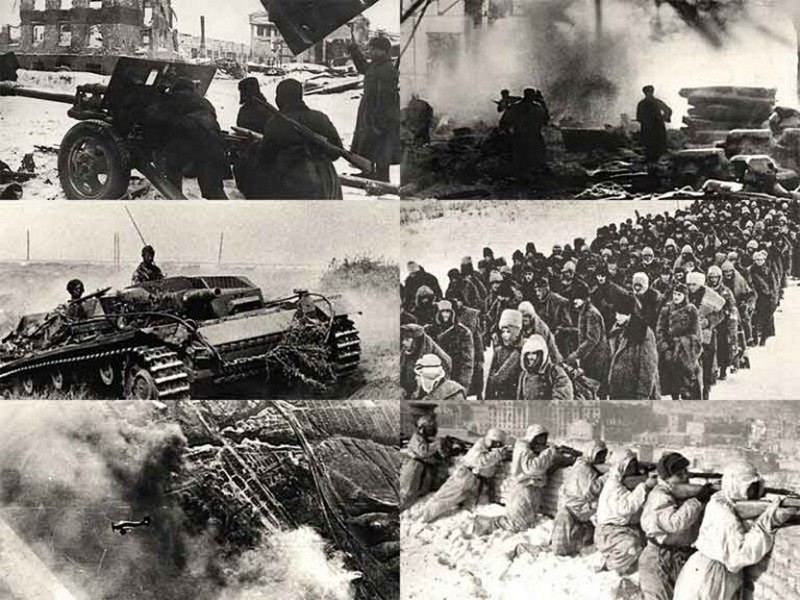

The year 2026 marks the eighty-third anniversary of the Battle of Stalingrad. The battle was not merely a decisive military engagement in the Second World War, but a historical rupture that reshaped the trajectory of the 20th century. Fought between August 1942 and February 1943, it marked the first total strategic defeat of Nazi Germany and shattered the myth of fascist invincibility upon which Hitler’s war of conquest depended. Yet in much of today’s dominant historical memory, particularly in the Anglophone world, Stalingrad is reduced to a dramatic episode, abstracted from its political meaning and severed from its consequences. This minimization is not accidental. To acknowledge Stalingrad as the turning point of the war is to acknowledge the centrality of the Soviet Union in the defeat of fascism, and, by extension, to confront the uncomfortable fact that the greatest victory over Nazism was achieved not by liberal capitalism, but by a socialist state fighting for its very survival.

In Western historiography and popular culture, the narrative of the Second World War has been persistently reorganized to center the United States and its allies as the principal agents of fascism’s defeat, while the Soviet contribution is treated as secondary, incidental, or morally compromised. Hollywood’s fixation on the Normandy landings in June 1944, the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944, and the Pacific theater stands in stark contrast to the relative silence surrounding the Eastern Front, where the war was decided. This imbalance is not a matter of oversight, but of ideology. From the early Cold War onward, the memory of the war was refashioned to reconcile two incompatible facts: that Nazism was the greatest crime of the 20th century, and that it was defeated primarily by a socialist state. The result has been a systematic downplaying of Soviet military, economic, and human sacrifice, replaced by a depoliticized narrative in which fascism collapses under the abstract weight of “Allied unity,” rather than being crushed through a protracted and devastating class war in the East.

Already in 1941, Operation Barbarossa was conceived not as a conventional military campaign, like those the Nazi war machine had conducted in the Low Countries or in France in 1940, but as a war of annihilation (Vernichtungskrieg), aimed at the physical destruction of the Soviet state and the biological, social, and political eradication of entire populations. Nazi strategy in the East fused military conquest with genocide: the planned starvation of tens of millions, the extermination of Jews, Roma, communists, and Soviet officials, and the reduction of Slavic peoples to a reservoir of slave labor.[1] As historian Stephen G. Fritz writes:

“Ostarbeiter (eastern workers), overwhelmingly young men and women, often just teenagers (their average age was twenty), were put to work, normally in deplorable conditions, in the Reich’s factories, mines, and fields. By the end of July, over 5 million foreign workers were employed in Germany, while, by the summer of 1943, the total foreign workforce had risen to 6.5 million, a figure that would increase by the end of 1944 to 7.9 million. By that time, foreign workers accounted for over 20 percent of the total German workforce, although, in the armaments sector, the figure topped 33 percent. In some specific factories and production lines, foreign workers routinely exceeded 40 percent of the total; indeed, by the summer of 1943, the Stuka dive bomber was, as Erhard Milch boasted, being “80% manufactured by Russians.” [2]

The Wehrmacht was not a neutral instrument dragged unwillingly into this project, but an active participant in it. Stalingrad must be situated within this context. It was not simply a battle for territory or supply routes, but a decisive moment in a war whose objectives were openly colonial and genocidal. To lose at Stalingrad was, for the Nazi leadership, to confront the first concrete limits of a project premised on unlimited violence.

The Eastern Front was not one theater of the war among others; it was the war. Between 1941 and 1944, the overwhelming majority of German military forces were deployed against the Soviet Union. “By October 1, 1943, some 2,565,000 soldiers—63 percent of the Wehrmacht’s total strength—were fighting in the East, as were the bulk of the 300,000 Waffen SS troops,” write historians David M. Glantz and Jonathan M. House. “On June 1, 1944, a total of 239 German division equivalents, or 62 percent of the entire force, were on the Eastern front.”[3] And it was there that the Wehrmacht suffered the vast bulk of its casualties. Approximately three-quarters of all German military deaths occurred on the Eastern Front, as did the destruction of entire armies whose loss could never be replaced. By comparison, the Western Front—while militarily and politically significant—opened only after the Red Army had already broken the backbone of Nazi military power. Stalingrad stands as the clearest expression of this asymmetry. It was on the banks of the Volga, not the beaches of Normandy, that the strategic initiative of the war was irreversibly seized from Hitler’s Germany.

The scale of the Soviet victory at Stalingrad cannot be understood without confronting the scale of the disaster that preceded it. When Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Red Army was caught profoundly unprepared for a war of such speed, coordination, and technological concentration. Entire formations were encircled and destroyed, millions of soldiers were killed or captured, and vast territories were overrun within months. This unpreparedness was not simply military, but structural: a rapidly industrializing socialist state faced an existential assault from the most advanced war machine capitalism had yet produced, backed by the resources of occupied Europe. Stalingrad therefore did not emerge from a position of strength, but from the edge of collapse. That the Soviet Union was able to absorb these blows, reorganize its economy, relocate its industry, and reconstruct its armed forces under conditions of total war is itself one of the most extraordinary, and least acknowledged, achievements of the twentieth century.

Stalingrad marked the moment when the Nazi war machine ceased to advance and began, irreversibly, to bleed. The German offensive toward the Volga in the summer of 1942 was intended to secure oil resources, sever Soviet transport routes, and deliver a symbolic blow to the heart of the Soviet state. Instead, it culminated in a protracted urban battle that nullified Germany’s operational advantages and drew its forces into a war of attrition it could not win. Street by street, factory by factory, the Red Army transformed Stalingrad into a killing ground that consumed entire German divisions. The encirclement and destruction of the Sixth Army was not merely a tactical defeat; it was the first time a full German field army was annihilated, rather than forced to withdraw. From this point forward, the strategic initiative passed decisively to the Soviet Union, and with it the fate of the war.

The victory at Stalingrad was purchased at a human cost almost without precedent, borne overwhelmingly by Soviet soldiers and civilians whose lives were subordinated to the imperatives of collective survival. Entire neighborhoods were reduced to rubble; hunger, exposure, and exhaustion were as lethal as artillery and bombs. Yet what distinguished Stalingrad was not simply endurance, but the social form that endurance took. The defense of the city relied on mass mobilization, political commitment, and a degree of collective discipline that cannot be explained through coercion alone. Workers fought in the ruins of the factories they had built; civilians sustained production and logistics under bombardment; soldiers held positions measured in meters, not kilometers. These were not abstract acts of patriotism, but expressions of a society fighting a war that threatened its very existence, and in which defeat meant not occupation, but annihilation.

The impact of Stalingrad extended far beyond the battlefield, reshaping the political and strategic landscape of the entire war. For the first time since 1939, fascist expansion was not merely slowed, but decisively reversed, sending shockwaves through Axis leaderships and occupied Europe alike. Just prior to the invasion Hitler had told to his generals, “We need only to kick the door in and the whole rotten structure will come crashing down.” For Hitler, and it should be said, for many of his generals and for large sections of the German population, the Soviet military was assumed to be incapable of matching the Wehrmacht. It was dismissed as rotten and weak, supposedly reflecting the inferiority of the peoples who made up the Soviet Union. This assumption, however, proved catastrophically false. The Red Army did not simply absorb defeat, it learned from it. Through bitter experience, it mastered the modern art of war, refining and applying the tactical and operational concepts of Deep Battle and Deep Operation with increasing effectiveness.[4] But not only that, resistance movements across the continent drew renewed confidence from the defeat of the German Sixth Army, while Allied strategic calculations were fundamentally altered by the realization that the Red Army would carry the war westward. Stalingrad also punctured the ideological aura of inevitability that had surrounded Nazi conquest, demonstrating that fascism could be defeated through sustained mass resistance rather than diplomatic maneuvering or technological superiority alone. From this point onward, the question was no longer whether Germany would lose the war, but how quickly and at what further human cost. That cost was determined by the increasingly fanatical resistance of Hitler’s army and the continued political and social support it received from large sections of German society.[5]

By the war’s end, the scale of the Soviet Union’s sacrifice dwarfed that of all other Allied powers. Approximately twenty-seven million Soviet citizens, soldiers and civilians alike, were killed, entire regions were devastated, and much of the country’s industrial and agricultural base lay in ruins. These losses were not incidental to victory; they were its material foundation. Yet in the postwar order that emerged under U.S. hegemony, this reality was increasingly obscured. As Cold War antagonisms hardened, Soviet suffering was detached from Soviet achievement, acknowledged in numbers but stripped of political meaning. Stalingrad was recast as a tragic episode rather than a decisive triumph, its significance diluted to accommodate a narrative in which socialism could not be credited with saving Europe from fascism. The debt owed to the Red Army was thus transformed into an ideological inconvenience—one to be minimized, relativized, or forgotten altogether.

This distortion of Stalingrad’s meaning is not confined to the past; it is an active political process in the present as well. Across Europe and North America, with the help of bourgeois historians and researchers; movies or video games, which form key components of the superstructure; the historical record of the Second World War is increasingly rewritten through the lens of anticommunism, equating fascism and socialism while obscuring the genocidal character of Nazi war aims. In this revisionist framework, the Red Army appears not as a force of liberation, but as a symmetrical oppressor, and the annihilation war waged against the Soviet Union is displaced by narratives of abstract “totalitarianism.” Such distortions serve contemporary imperial interests, legitimizing the rehabilitation of far-right movements, the militarization of historical memory, and the normalization of endless war. To remember Stalingrad accurately is therefore not an act of nostalgia, but an act of resistance against the political uses of forgetting.

Stalingrad offers no comfortingly simple lessons, but it does offer clarity. It demonstrates that fascism is not defeated by moral appeals, institutional gradualism, or abstract commitments to “democracy,” but through organized, collective struggle capable of confronting imperial violence at its roots. It reveals the scale of sacrifice demanded when capitalist crisis turns toward exterminatory war, and the price paid when such a war is allowed to advance unchecked. Above all, Stalingrad affirms that history is not moved by inevitability, but by mass action under conditions of extreme constraint. The Soviet victory was neither accidental nor preordained, it was forged through political will, social mobilization, and a readiness to endure losses that liberal societies—then and now—prefer not to imagine.

As the anniversary of the Battle of Stalingrad is marked, the question is not simply how the battle is remembered, but who controls its meaning. To treat Stalingrad as a distant tragedy or a neutral military episode is to evacuate it of the historical force it still carries. It was there that the Nazi project of annihilation was broken, and it was there that the fate of the war, and of millions beyond the battlefield, was decisively altered. At a moment when fascism is again normalized, imperial war once more presented as necessity, and socialism routinely dismissed as historical error, Stalingrad stands as an enduring counterpoint. It reminds us that the greatest defeat of fascism in history was achieved through collective resistance, social organization, and the uncompromising defense of a future that, at the time, could not yet be guaranteed.

Notes

[1] Stephen G. Fritz, Ostkrieg: Hitler’s War of Extermination in the East (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2011), xx; Hans Heer and Christian Streit, Vernichtungskrieg im Osten: Judenmord, Kriegsgefangene und Hungerpolitik, 2020.

[2] Fritz, Ostkrieg, 222. Milch was the State Secretary in the Reich Ministry of Aviation from 1933 to 1944 and Inspector General of the Luftwaffe from 1939 to 1945.

[3] David M. Glantz and Jonathan M. House, When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2015), 357.

[4] David M. Glantz, Soviet Military Operational Art: In Pursuit of Deep Battle (New York: Frank Cass, 1991).

[5] Nicholas Stargardt, The German War: A Nation Under Arms, 1939–1945 (New York: Basic, 2015).

Tunç Türel is an Ancient Historian and a member of the Workers’ Party of Türkiye.

29 January 2026

Source: countercurrents.org