By Sara Toth Stub

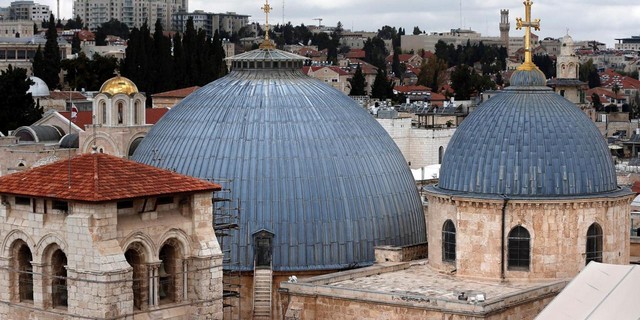

On a recent Sunday morning, Adeeb Jawad Joudeh Al Husseini was sitting on a bench just inside the sole public entrance to Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The doorway to the sprawling church, founded in the 4th Century, is where the 53-year-old Muslim has spent much of his life. His father, grandfather and dozens of generations of forefathers before them also dedicated most of their lives to sitting on this bench, guarding the church believed to contain the tomb of Jesus, Al Husseini said, pulling a 20cm-long iron key out of his leather jacket’s inner pocket.

This key is the only one that can unlock the church’s imposing wooden doors, a duty that was, according to Al Husseini, given to his family by Saladin, the sultan who captured Jerusalem from the Crusaders in 1187 – just one of many times that control of Jerusalem, coveted for its holiness by Jews, Christians and Muslims, has switched hands. Saladin wanted to make sure that the church was not harmed by his fellow Muslims, something that happened in 1009 when the Fatimid caliph al-Hakim ordered a number of churches in the Holy Land be burned, including the Holy Sepulchre. (Al-Hakim’s son approved the rebuilding of the church in 1128.)

“So Saladin gave our family the key to protect the church,” Al Husseini said. “For our family, this is an honour. And it’s not an honour just for our family, but it’s an honour for all Muslims in the world.”

Members of Al Husseini’s family, along with another Muslim family, the Nuseibehs, have become permanent fixtures in the complicated fabric of the Holy Sepulchre church. The complex is now used by six different ancient churches – Roman Catholic, Greek Orthodox, Armenian Orthodox, Syrian Orthodox, Ethiopian Orthodox and Coptic Orthodox – each of which has monks living there. Throughout history, relations have been fraught between the religious communities in this complex, sometimes leading to violence over which church controls which parts of the building. To this day, a 19th-century Ottoman decree attempts to keep these tensions in check by declaring that each church is limited to using the spaces in the building that they controlled back in 1853 when the decree was issued.

Every morning when the church’s doors open at 4 am, members of the two families – or a representative appointed by them – is present for what has emerged as a ceremonial act of cooperation. The Muslim representative unlocks the latch and pushes open one door, then a clergyman from the Roman Catholic, Greek Orthodox or Armenian Orthodox church – who take turns on a rotating basis – pull open the other door from inside, while clergy from the other denominations supervise. The same happens in reverse when the church closes at 7 pm.

The tourists and pilgrims who come here to kiss the stone slab revered to be the place where the body of Jesus was washed before burial, and enter the underground chamber believed to contain his tomb, all walk past these Muslim guardians, who sit on the bench much of the day in between tending to family and business. Historians cannot determine how long the role of these doorkeepers goes back, but they also haven’t made serious attempts to disprove the legacy – and most consider it central to the daily operations of the church.

“It’s basically like a lot of things in the church; it’s a tradition,” said Raymond Cohen, professor emeritus of international relations at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, who has studied the church and written the book, Saving the Holy Sepulchre. “And I think it’s one of the gems of Jerusalem, really.”

While Al Husseini’s family holds the key, the Nuseibeh family is charged with the physical work of opening and closing the church’s door, a duty they trace back to 637 when the caliph Omar first brought Islam to Jerusalem, explained Wajeeh Y Nuseibeh, 67, who was sitting on the bench next to Al Huseini.

“Our family first arrived to Jerusalem with Omar,” and since then has been entrusted to protect the church from vandals, Nuseibeh said, handing me his business card, which declares he is “Custodian and door-keeper of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre”.

But Al Husseini insists that Nuseibeh’s family only entered the set-up later.

“This is not true what [Nuseibeh] says,” Al Husseini told me later, adding that shortly after his family received the keys from Saladin in 1187, they asked the Nuseibeh family to open and close the door, which involves climbing a ladder to reach the lock, while Al Husseini’s family remained the holder of the key.

“It was not honourable for our family to be climbing up and down ladders, because we were sheiks,” Al Husseini said.

Al Husseini’s card says he is “Keys Custodian of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.”

Nuseibeh smiled at Al Husseini’s version of the story, then repeated his own version, going back to Omar, who ruled the city more than 500 years before Saladin. Sitting side by side, they told me that the matter is a friendly debate and something they often laugh about, an account confirmed by a mutual friend, Ibrahim Attieh, 75, a retired tour guide who joined them on the bench to chat.

“Yes, they are friends, and I am a friend of both of them,” said Attieh, who was one of the many friends, priests, tourists and even Israeli police officers (who oversee security in the church) to join Al Husseini and Nuseibeh on their bench during the day.

In addition to surviving the whims of Jerusalem’s governing powers, including hundreds of years when the caliphate charged pilgrims large sums of money to enter, the church has also been torn by inner conflict. Throughout history there have been clashes – sometimes violent – between various denominations over control of certain areas of the church, and the local powers, especially during Ottoman times, were often involved in redistributing rights and territories inside the building.

Occasionally, these disagreements even threatened to spark conflict between world powers. In 1853, Russia threatened to invade Turkey if its Ottoman government, which also controlled Jerusalem, granted France’s request to give part of the Greek Orthodox area of the church to the Roman Catholics. This caused the Ottoman sultan Abdulmecid I to issue the decree saying that there would be no more transferring of property and rights inside the church.

Today, this so-called status quo that was imposed on the denominations still governs every facet of life in the church, from the scheduled times of services, to the languages of the Masses, to the route a procession takes. Any change to the routine risks discord and violence, last demonstrated in 2008 when a brawl broke out between Greek Orthodox and Armenian Orthodox clergy over the route of a procession, leading to arrests. The delicate nature of keeping the status quo means that renovations and repairs are rare, Cohen explained.

“It’s no simple task to keep the peace,” he said.

But after decades of negotiations, Roman Catholic, Armenian and Greek Orthodox leaders recently came to a historic agreement to repair the structure covering what they believe is Jesus’ tomb, which architects have long warned is in danger of collapse. The square structure, known as the Edicule, located under the church’s main rotunda, is now covered in scaffolding. Ladders, stone slabs, plywood and other building supplies have been scattered around the centre of the church since June 2016. This is first repair work to be done to the tomb’s chapel in more than 200 years and the first significant project for any part of the building since the edifice was restored, beginning in the 1960s.

But even though the churches may now cooperate better than in the past, and can rely on the Israeli police to keep order, the doorkeepers are an embodiment of how long-held traditions and the involvement of outsiders has determined much of the course of the Holy Sepulchre’s history.

“Things are like a wool sweater here; if you start unravelling it, the whole thing falls apart,” Cohen said.

At 6:30 pm on Sunday evening, half an hour before the church’s scheduled closing, a loud clanging pierced the quiet in the church. This was the sound of Omar Sumren performing the ritual banging of the knocker, then shutting one of the double doors in preparation for the final closing. Sumren and his brother, Ishmael, have worked on behalf of Al Husseini for 25 years, performing the opening and closing duties when Al Husseini is busy.

Just before 7 pm as the last visitors were leaving, Ishmael picked up the ladder resting inside the church’s doors and moved it outside. Two Catholic Franciscans clad in their signature brown gowns with rope belts, along with Greek and Armenian Orthodox priests dressed in black, stood inside the threshold, observing every move. An Israeli policeman, wearing a yarmulke, or Jewish skullcap, was also present for the daily ritual. Ishmael shut the door then ascended the ladder to close the upper latch. He climbed down, folded up the ladder and passed it back to the priests inside through a small hatch in the door.

As the monks began another night inside the church compound, Omar, entrusted with the key from Al Husseini, retired to a small room just off the main courtyard in front of the church. Each night one of these men tasked with the door and key duties sleeps here, ready to perform the regimented opening in the morning.

“This for me is a second house,” Al Husseini said.

28 November 2016