Chandra Muzaffar

Paper presented at the Fourth Global Inter-Religious Conference on Article 9 and Global Peace Transcending Nationalism at YMCA Asia Youth Center in Tokyo from 1st to 5th December 2014.

On the 1st of July 2014, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and his Cabinet decided to re-interpret Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution to enable Japan to exercise “collective self-defense.” What this means in effect is that Japan can now get involved in military operations in other countries as long as they are in Japan’s interests. She can send her troops to other lands and sell her military hardware to other states.

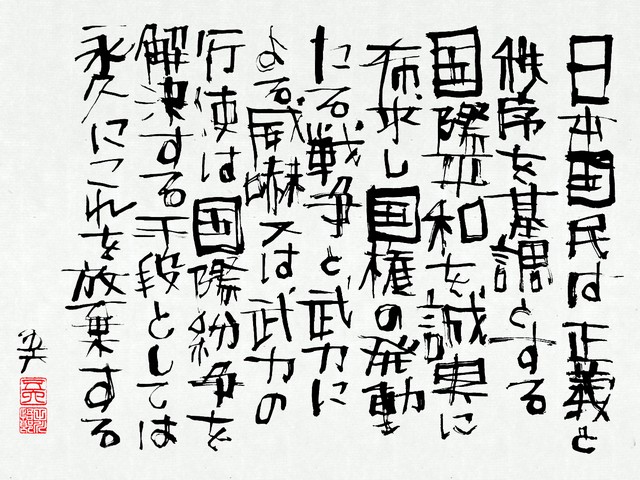

This represents a major shift for a nation which after the second world war adopted a constitution that states clearly that “aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as a means of settling international disputes”. (Article 9) (1)

As an aside, it may be observed that though war is renounced in its Constitution, “Japan has a well-equipped standing military (also known as Self-Defense Forces) of 225,000 personnel, including by most conventional standards, a formidable Navy (Maritime SDF).” (2) Based upon its share of world military expenditure in 2013, Japan occupies the eighth position globally, tying with Germany. Its actual military expenditure for that year amounted to 48.6 billion dollars. (3) This makes Japan — even before its re-interpretation of Article 9 — one of the most formidable military powers on earth.

Influences

It is against this background that we should look at the re-interpretation of Article 9 which undoubtedly has been influenced by a number of factors. There has always been a view within Japanese society associated with the political Right that only a militarily strong Japan would be able to defend its vulnerable, insular situation and circumstance. Besides, it is only with military muscle that the nation would be able to ensure that it has the capacity to secure oil and other much needed natural resources in which it is so deficient. As a prominent global economic actor, Japan also has no choice but to protect its vast economic assets which the Right believes requires military strength. (4)

The rise of Abe has also played a major part in the reinterpretation of Article 9. A right-wing nationalist who has downplayed Japan’s war-time atrocities, including the issue of comfort women in Korea and other Asian countries and who insists that class A war criminals are not criminals under Japanese domestic law, Abe has increased defense expenditure since becoming Prime Minister for a second time in December 2012. He has also announced a five year military expansion plan. On a number of regional issues, involving notably China and South Korea, Abe has adopted a belligerent stance. His solid majority in parliament — his party, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) commands 294 out of 480 seats in the Lower House — has given him the confidence to pursue a militaristically oriented nationalistic policy.

It is not without significance that Abe’s rise has coincided with the “US pivot to Asia”. The phrase itself is a misnomer since the US has remained a principal political and economic force in Asia, in spite of its defeat in Vietnam in the seventies and the closing down of its air and naval bases in the Philippines in the nineties as a result of a popular uprising. Describing its current approach to Asia as a sort of “re-balancing” is also off the mark since the assumption is that there is already a dominant power in our continent that the US is helping to check or re-balance. What the US is doing is to re-assert its power in Asia in an organized and systematic manner. Japan is certainly central to that strategy.

The re-assertion of US power is driven by at least three factors. One, the rise of China as an economic powerhouse in the region and globally which has endowed it with increasing political clout. The US views this as a challenge to its hegemony. Two, the emergence of Asia as the epicenter of the global economy with China, Japan and South Korea playing pivotal roles. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and possibly India are also important in this changing scenario. The US wants to ensure that it has a huge slice of the Asian cake. Three, because of factors one and two, the US fears that if it does not re-assert its power at this stage it will not be able to perpetuate its position as the world’s leading economy and its sole military superpower. To put it differently, the re-assertion of US power in Asia today is about the maintenance of its global hegemony.

The US knows that it cannot achieve this goal without the support and cooperation of its allies such as Japan. After two expensive wars in two countries, Afghanistan and Iraq, in the last 13 years, the US needs Japan’s financial wherewithal to sustain its military infrastructure in Asia. This is why it has been pushing Japan to go beyond Article 9 and commit itself to US- led military operations in other parts of the world. That push has become more concerted in light of the US’s own economic decline and the rise of China as an economic power.

That Japan shares the US fear of China’s rise is an understatement. It is said in some circles that when China overtook Japan as the world’s second largest economy it made a dent on the Japanese psyche. But more than the question of economic ranking, there is a serious maritime dispute over the Senkaku Islands (the Chinese refer to them as Diaoyu) which has widened the rift between the two nations. (5). Competing claims over the five tiny islands and three rocks covering a mere seven square kilometers have gotten worse since 2010 leading to several clashes in recent years. This maritime conflict should be viewed against the backdrop of China’s deep unhappiness over Japan’s invasion and occupation of parts of China from 1937 to 1945 and the latter’s reluctance to issue a genuine apology over the war and the accompanying atrocities. (6). Because this has always rankled the Chinese collective memory, the Japanese Right is convinced that China will remain hostile towards Japan and Japan should accordingly be mil

itarily prepared to deal with this reality.

For the Right in Japan, the South Korean public also feels the same way about Japan. The Japanese colonization of Korea for 35 years from 1910 to 1945 left an indelible mark upon the Korean psyche. It is partly because of the suffering and humiliation that the people went through that the Koreans remain angry and bitter about the issue of Korean comfort women and sex slavery in general. Instead of demonstrating genuine remorse for what had happened in the past, the present Japanese leadership in particular appears to be skirting around the issue through all sorts of rationalizations. The Right sees Koreans as implacable and that becomes a justification for its own agenda of greater military alertness on the part of Japan.

Then there is North Korea or the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). Its nuclear tests and its military stances have helped to strengthen the hand of the Japanese Right and those who are in favor of a re-interpretation of Article 9. They argue that North Korea is a constant reminder of the dangers that lurk in Japan’s neighborhood.

If the proponents of re-interpretation have discovered yet another argument it is in the tensions that are expressing themselves in the region from the re-assertion of US power, on the one hand, and the rise of China, on the other. The maritime dispute between the Philippines and China over what the former calls the Scarborough Shoal and the latter calls the Huangyan Island which has led to a series of collisions have drawn in both the US and Japan(7). Initially, it was just the US at times encouraging and at times provoking the Philippines, its longtime ally, to adopt a hardline position against China. Now Japan has also come out in support of the Philippines through its promise of closer security ties (8). Japan is also forging stronger military relations with Australia, another intimate US ally in the region. (9)

To these ties with the two US allies, one should also add Japan’s growing friendship with India. Some foreign policy analysts in both countries regard the rapport between Japanese Prime Minister, Shinto Abe, and the new Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, as a bond borne of their common concern for China’s rise — a bond that the US would like to see getting stronger as a counterweight to Chinese power (10). It would serve the US’s larger agenda of containing China while engaging her. (11)

From the various influences shaping Article 9, it is obvious there are significant geopolitical and geo-economic forces propelling Abe and Japan in a certain direction. The desire and determination of the US elite to pursue and perpetuate its hegemony with the active collaboration of surrogates such as Abe’s Japan is a critical factor. Sometimes the drive for hegemony reinforces longstanding frictions and conflicts among neighbors in the region. At other times, current disputes and disagreements are igniting fresh tensions. But whatever the actual dynamics, the importance of Article 9 goes beyond Japanese shores.

This is why it is crucial to examine the implications and consequences of Article 9 for Japan, for Asia and for the world.

Implications and Consequences.

For Japan, the re-interpretation of Article 9 could lead to a vigorous resurgence of the political Right — a resurgence not witnessed since the end of the second world war. The military budget could be increased substantially. There could be greater acceptance of military bases, including those in Okinawa. There may even be a push for developing nuclear weapons. Japan could be inducted into military alliances. It may even take a lead role in military adventures abroad.

At the same time, the militaristic trend could prompt peace movements to re-organize and re-strategize with a greater sense of purpose. The opposition to US bases in Japan could become stronger. The campaign against not just nuclear weapons but also nuclear plants that generate nuclear energy for electricity and other peaceful purposes could gather momentum. The Japanese people may mobilize against military alliances and sending combat soldiers abroad. There may even emerge a powerful movement to compel the elite to adhere to the original meaning of Article 9 as envisaged in the Constitution.

Outside Japan, in the rest of Asia, the resurgence of Japanese militarism would be viewed with grave concern. Though the actual victims of Japanese aggression including the diminishing cohorts of comfort women may not be around in a few years’ time, the collective memories of Japanese atrocities in various Asian countries will live on forever. Even among allies such as the Philippines, there will be no jettisoning of this memory of pain and suffering.

It is quite conceivable that as a reaction to Japanese militarism, other countries could expand their military budgets. There could be an arms race in the region. Even as it is, there is an arms build-up in Asia which the mainstream Western media and its Asian counterparts are blaming upon the so-called China threat. (12). The truth is that China — unlike Japan or Western nations — has not conquered or occupied any other country. If Asian countries have to fear conquest or occupation, the threat from Japan and the West is more real — based upon historical facts — than an imaginary threat from China. This is the reason why a militarily resurgent Japan is a much greater danger to the rest of Asia than a China reacting to a re-assertive United States.

As in the case of Japan, militarization in various Asian countries may induce peace groups to enhance their commitment. They may speak up against their governments for not only increasing their military expenditure but also for forging military links with other states that only serve to escalate tensions and frictions in the region. In this regard, I can see peace activists in countries such as the Philippines and India voicing their opposition to any attempt to establish a special military relationship with the US or with the US through Japan.

This brings us to the US’s role in Asia and the world mediated through Japan. Since the US’s hegemonic power is declining — as pointed out by a number of thinkers and analysts from different parts of the world (13) — any move to perpetuate its hegemony by getting allies like Japan to employ money, men and machine on its behalf would be resented by a lot of people who realize that US dominance and control has been a bane upon humankind. Japan would also incur the wrath of an expanding segment of the global community. Indeed, if Japan plays this surrogate role, it is very likely that whatever goodwill Japan has accumulated over the decades especially in Asia as a result of its extensive business and trade ties in the region will dissipate quickly. Japan, in other words, will be perceived in an extremely negative light.

Opposition to Re-Interpretation of Article 9.

Though Japan’s militaristic role in the future and the US’s continuing attempt to perpetuate its hegemony may be detrimental to the interests of the people, at the moment there does not seem to be much opposition to the re-interpretation of Article 9 in countries outside Japan. It has not become a major concern among the masses anywhere in Asia or the West for that matter.

This is mainly because of the media which has not given any emphasis to the question of Article 9. There has been hardly any in-depth analysis of the issue in any major media outlet in the continent outside Japan. Most people are just ignorant of Article 9 and what it implies and how it will impact upon their own lives. No non-Japanese NGO in the region of some weight (with the exception of some Church groups) has campaigned vigorously against the re-interpretation of the Article. Intellectuals in Asia as a whole have given scant attention to this vitally crucial issue that will have an enormous impact upon present and future generations.

The exception as I have alluded to are some Churches. It is significant that the central committee of the World Council of Churches (WCC) itself meeting in Geneva from 2nd to 8th July 2014 adopted a resolution which: –

1.“Expresses its grave concern at the direction indicated by the Japanese government’s initiative to reinterpret or change article 9 of the constitution, and its impact on regional security, on the positive example provided by this constitutional prohibition, and on efforts towards global peace and non-violence;

2. Calls on the Japanese government to honour and respect both the letter and the spirit of Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution which upholds non-violence as a means to settle disputes;

3. Urges the government of Japan to live up to its “Peace Constitution” and build non-military collective peace and security agreements with all neighbouring states in Northeast Asia;

4. Encourages the Japanese government not to surrender to external pressures to change or re-interpret Article 9 of their Constitution;

5. Invites member churches to accompany the struggles of peace-loving Japanese people and churches in prayer.” (14)

Though the Abe government has yet to respond positively to the WCC resolution, the churches’ bold and brave stand is commendable. It is the sort of stand that an institution founded upon religious principles should take when confronted by a fundamental moral issue.

Others Should Also Stand Up.

If Christian institutions and groups are prepared to openly oppose the re-interpretation of Article 9, there is no reason why people of other faiths should not also make their voices heard. After all, any move that justifies war and violence in whatever guise is unacceptable to all the religions. All religions value life, each and every life. Because people of faith cherish the sacredness of life, the destruction of life is abhorrent to them.

In this regard, Muslims and Islam have an important role to play. (15) The Muslim population of Japan may be infinitesimal but Islam is the religion with the biggest number of followers in Asia. Muslims should be concerned about the re-interpretation of a law that will alter significantly Japan’s role in Asia and as a result change the political landscape of the entire continent.

To re- interpret “collective self-defense” to legitimize the formation of military alliances and Japan’s participation in foreign wars goes against the concept of resisting aggression or fighting oppression in Islam. The wars that Japan’s protector, the US, has helmed since the early sixties have been essentially wars of aggression. Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq would be three examples. It is towards these types of wars that Japan would be expected to contribute money, men and machine. Muslims should not only oppose these types of wars but also reject any attempt to camouflage their real intent through the usage of terms such as “collective self-defense.”

It should also be emphasized that resisting aggression or combating oppression through arms — legitimate as it is in Islam as in international law — is but an act of last resort. It is only when other peaceful, non-violent means of resolving a conflict have failed that one is permitted to protect one’s integrity and dignity as a victim of aggression and oppression by taking up arms. What this implies is that the peaceful resolution of conflicts is the preferred option in Islam. Building a culture that encourages this is the religion’s real aim (16). This is why Article 9 and Japan’s Peace Constitution would be highly prized in Islamic thought. Islam would want laws and constitutions of this kind to be promoted and popularized since they bring forth the essence of the faith.

Conclusion.

At a time when Article 9 is being re-interpreted, people of faith everywhere and indeed, all human beings, should join hands and reiterate the singular significance of the Article to the future of humankind. We should not just be reactive. We should be proactive and proclaim to the world that it is this Article in its original sense that should be incorporated into the constitution of every nation on earth.

This would be in line with what we did at the ‘Inter-Religious Conference on Article 9 and Peace in Asia’ held in Tokyo from 29 November to 1st December 2007. We called upon religious circles and persons in Asia and the world to:-

1) “Treasure Article 9 as a patrimony of the whole of the human race and establish a global Article 9 network.

2) Encourage a clause in favor of demilitarization and renunciation of war to be included in the constitution of every nation.

3) Chart a new path for human history, using every opportunity to publicly call for the abolishment of all war.” (17)

There were many other messages that emanated from that conference. Seven years later, as we encounter a determined drive by powerful forces within and without Japan to change the very meaning of Article 9 in order to pursue their agenda of hegemony through war and violence, we would do well to re-dedicate ourselves to the ideas and ideals that the conference presented to the world.

We should perhaps do something more. We should pledge to ourselves that each of us will do what we can to translate those lofty goals into concrete realities. For deeds speak louder than words.

Dr. Chandra Muzaffar is President of the International Movement for a Just World (JUST)

Malaysia.

16 September 2014.

END NOTES

1) Quoted from Concept Paper for WCC Busan Madang Workshop Article 9 of the Japanese Peace Constitution, November 7 2013.

2) See B.A. Hamzah, “Abe-san walks a tightrope” New Straits Times, August 11, 2014.

3) Sourced from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI)’s Yearbook 2014. Online version.

4) See my “Article 9 and the Militarized World — What Can We Do?” Paper presented at the Inter-Religious Conference on Article 9 and Peace in Asia,

Tokyo, November 29 — December 1, 2007.

5) See my “The China Japan Dispute Over Diaoyu : Let The Truth Prevail!” JUST Commentary October 2012.

6) See Wikipedia Second Sino-Japanese War.

7) See my “An ASEAN-China Forum for the South China Sea” JUST Commentary June 2012.

8) Julius Cesar I. Trujano, “Japan and the Philippines Unite Against China” East Asia Forum 21 August 2013.

9) Andrew Carr and Harry White, “Japanese Security, Australian Risk? The Consequences of our Special Relationship.” The Guardian.com 8 July 2014.

10) See Mitsuru Obe and Niharika Mandhana, “India and Japan Pursue Closer Ties to Counter China,” The Wall Street Journal 1 September 2014.

11) For an analysis of this strategy see my “ Containing China: A Flawed Agenda,” in my Hegemony, Justice; Peace ( Shah Alam Malaysia: Arah Publications, 2008)

12) For example see “Asia arms up to keep rising China threat at bay,” New Straits Times 12 September 2014.

13) There have been a number of studies on the decline of the United States. Among them, Richard Falk, The Declining World Order (New York: Routledge, 2004) and James Petras Zionism, Militarism and the Decline of US Power (Atlanta, USA: Clarity Press, 2008). I have also been writing on the signs of an American decline for almost 12 years now. My latest thoughts on it can be found in, “The decline of US helmed Global Hegemony: The Emergence of a More Equitable Pattern of International Relations? in my A World in Crisis: Is There a Cure? ( www. Just-international.org, 2013) ( e-book)

14) See Statement on the Re-interpretation of Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution Documents ( Geneva: World Council of Churches, 2014) p. 2

15) I make this point in my paper “Article 9 and the Militarized World… Op.Cit at the Inter-Religious Conference on Article 9 and Peace in Asia held in Tokyo from 29 November to 1st December 2007.

16) For some reflections on Islam’s commitment to peace see Hassan Hanafi, Islam in the Modern World Vol 11 ( Heliapolis, Egypt: Dar Kebaa Bookshop, 1995) especially the section on “ Islam and World Peace.”

17) See Statement from Inter-religious Conference on Article 9 and Peace in Asia, November 29 — December 1, 2007 in Article 9 Global Inter-Religious Conference, p.23